Home »

Misc »

How far out is the 3 point line in basketball

How far out is the 3 point line in basketball

USA Basketball - The History of the 3-Pointer

On November 13, 1967, the Indiana Pacers of the American Basketball Association were losing to the Dallas Chaparrals, 118-116, with just one second left on the clock.

Indiana inbounded the ball to Jerry Harkness, who was 92 feet away from the basket. With no time to do anything else, Harkness threw a towering Hail Mary heave toward the goal. It smacked off the backboard and went in.

Pandemonium erupted in Dallas, but for all the wrong reasons. You see, 1967 was the first year of the 3-point shot among basketball's top leagues, and the players and fans weren't used to it. A lot of the 2,500 in attendance that day thought that the Harkness miracle tied the game and forced overtime. In fact, he was 68 feet behind the brand new 3-point line. His shot won the game for the Pacers, 119-118.

"We were running off the floor to huddle up for the overtime when the official, Joe Belmont, came up to me and said 'Jerry, it's over.![]() That was a 3-pointer,'" Harkness said in the book Loose Balls. "I said, 'I forgot all about that. A 3-pointer.' Then we were celebrating again, because we found out that we won the game."

That was a 3-pointer,'" Harkness said in the book Loose Balls. "I said, 'I forgot all about that. A 3-pointer.' Then we were celebrating again, because we found out that we won the game."

These days, the 3-pointer is second-nature to basketball players and fans. It's a safe bet that nobody under the age of 30 has any recollection of college or professional basketball being played without a 3-point line.

But, in fact, basketball was played for a long time without the 3-point shot. The NBA considered it gimmicky for years. The NCAA was even slower to adopt the rule.

Once it became mainstream, though--with the ABA leading the charge in 1967--basketball would never be the same again.

The Inception

The 3-point line's first use in a professional league was back in 1961 in the American Basketball League. The ABL only lasted 1 ½ seasons before folding, so the 3-pointer quickly went away.

The NBA, which had been around since 1946, never seriously considered it at that point. But when a new league competing against the NBA was dreamed up in the mid-1960s, the 3-point shot was back in the spotlight.

But when a new league competing against the NBA was dreamed up in the mid-1960s, the 3-point shot was back in the spotlight.

The ABA, which started in 1967, differed from the NBA in its experimentation of fan-friendly ideas. They had a red, white and blue basketball, a slam dunk contest, and of course, the 3-point shot.

According to the book Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association, which chronicled the nine-season history of the ABA, league organizers had planned to use the 3-pointer from the beginning. Coincidentally, the commissioner of the ABA and a big proponent of the 3-pointer was George Mikan, a 6-foot-10 NBA legend who probably would've never shot one during his playing days.

"We called it the home run, because the 3-pointer was exactly that," Mikan said in the book. "It brought fans out of their seats."

In 1976, the ABA and NBA merged, with four teams joining the NBA--the Indiana Pacers, San Antonio Spurs, Denver Nuggets and New Jersey Nets. The 3-point shot, at first, wasn't part of the package.

The 3-point shot, at first, wasn't part of the package.

The NBA stayed firm in the game's traditions. The league didn't adopt the 3-pointer until 1979--Magic Johnson and Larry Bird's rookie season. While certain college basketball conferences experimented with it in the early '80s, the NCAA didn't universally implement a 3-point line until 1986, with high school basketball following suit a year later.

The Adjustment

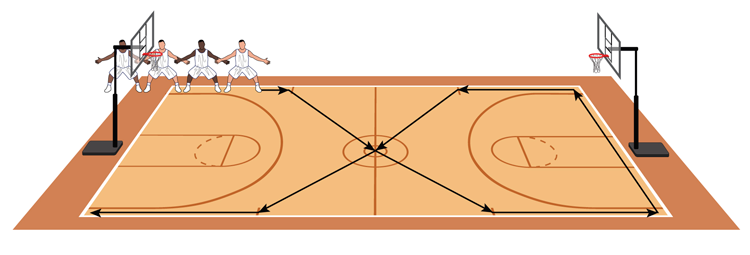

In the late 1960s, when the ABA introduced the 3-pointer, a generation of coaches had to rethink everything they knew about the game, and it made things hectic. One ABA coach admits that at first, he never used the 3-pointer unless his team was losing late in the game and was desperate for points.

Other coaches had similar problems adjusting to its reality.

"You have to tell your players to remember who the shooters are, and when those guys are 25 feet from the basket, get in their jocks and guard them," former ABA and NBA coach Hubie Brown said in Loose Balls. "Don't give them the 25-footer, which is something players had been conditioned to do all their lives. And as a coach, if you have a shooter with range, you have to give him the freedom to take the 25-footer, which is a philosophy that goes against what you learned as a young coach--namely, pound the ball inside."

"Don't give them the 25-footer, which is something players had been conditioned to do all their lives. And as a coach, if you have a shooter with range, you have to give him the freedom to take the 25-footer, which is a philosophy that goes against what you learned as a young coach--namely, pound the ball inside."

It wasn't just the coaches, either. The fans loved it right away, but there were growing pains among the players.

"It took a while for players to understand time and score situations, when to take it," said Len Elmore, who played in both the ABA and NBA. "You also recognize that players who hadn't been accustomed to playing with a 3-point line really had to work to develop the range."

Michael Jordan is a perfect example of that. He played college basketball at North Carolina without a 3-point line. In his rookie season with the Chicago Bulls, he was 9-for-52 from 3-point range. He never shot better than 20 percent from long range until his fifth season in the NBA. But by the time his remarkable tenure with the Bulls wrapped up, he was consistently shooting better than 35 percent from 3-point range.

But by the time his remarkable tenure with the Bulls wrapped up, he was consistently shooting better than 35 percent from 3-point range.

The Evolution

It may not be obvious, but the 3-point line continues to change the sport today.

"Guys have become super efficient at the shot," Elmore said. "You see the NCAA continue to move the line further back because players can shoot it. At one time, it was only 19 feet at its shortest point."

In addition to the players continuing to improve, the utilization of the shot continues to evolve as well.

"Now you're seeing it on the fast break, whereas coaches from old school wouldn't want you to take that shot on the break. They'd want you to challenge the defense and get the highest percentage shot," Elmore said. "Also, you're seeing guys now driving to the basket, and even though they have an opportunity to take the layup or a much shorter shot, they're more willing to kick it out to the wide-open 3-point shooter. I'm not sure the percentages work from that standpoint, but it's a trend. "

"

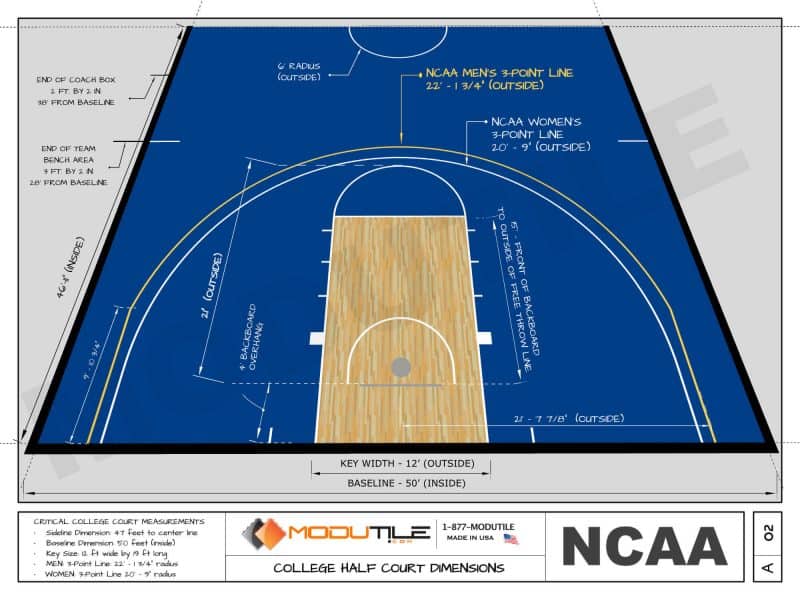

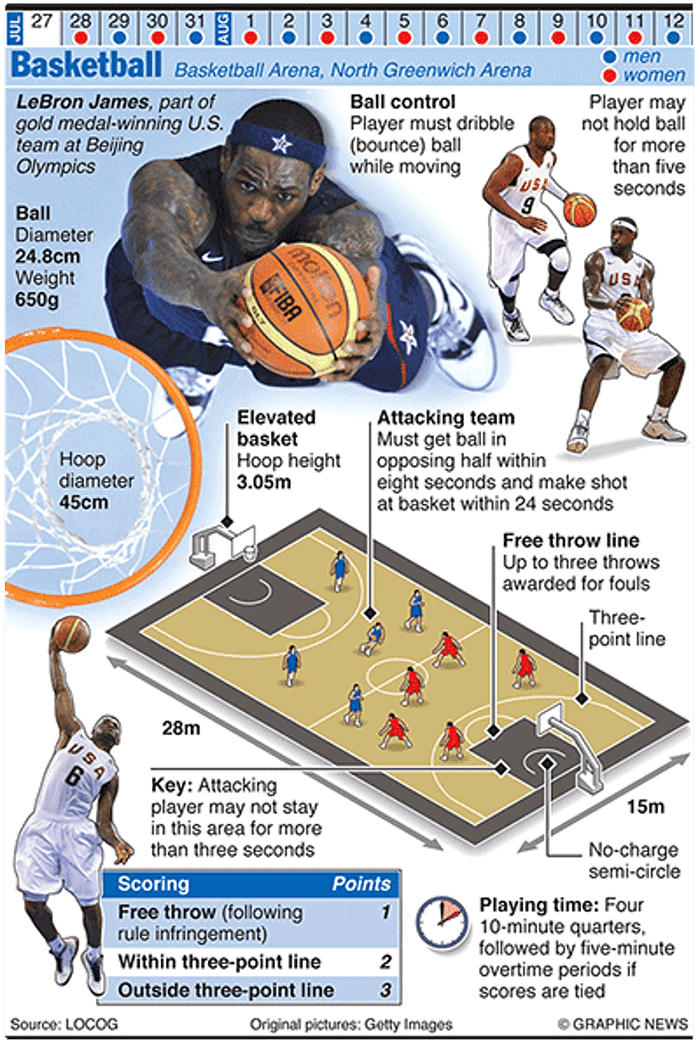

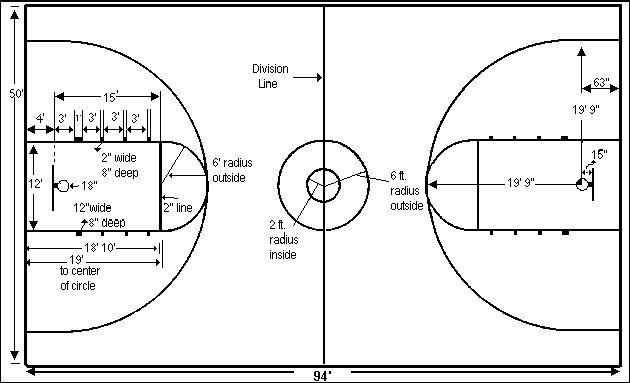

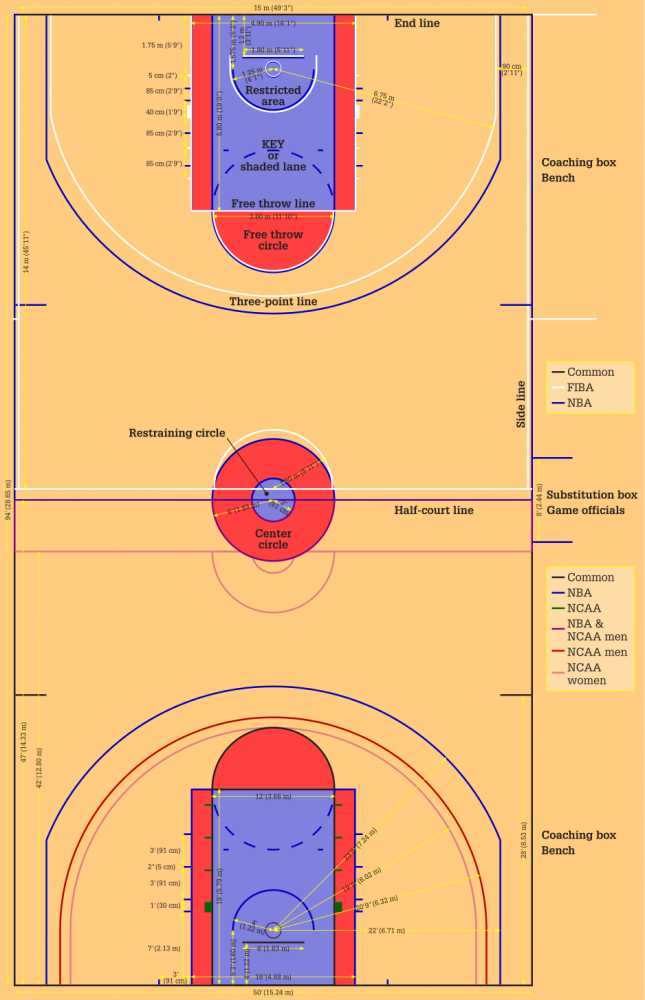

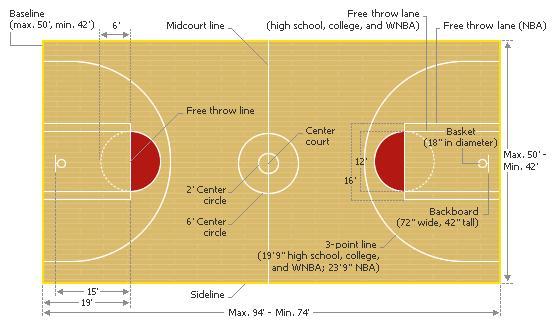

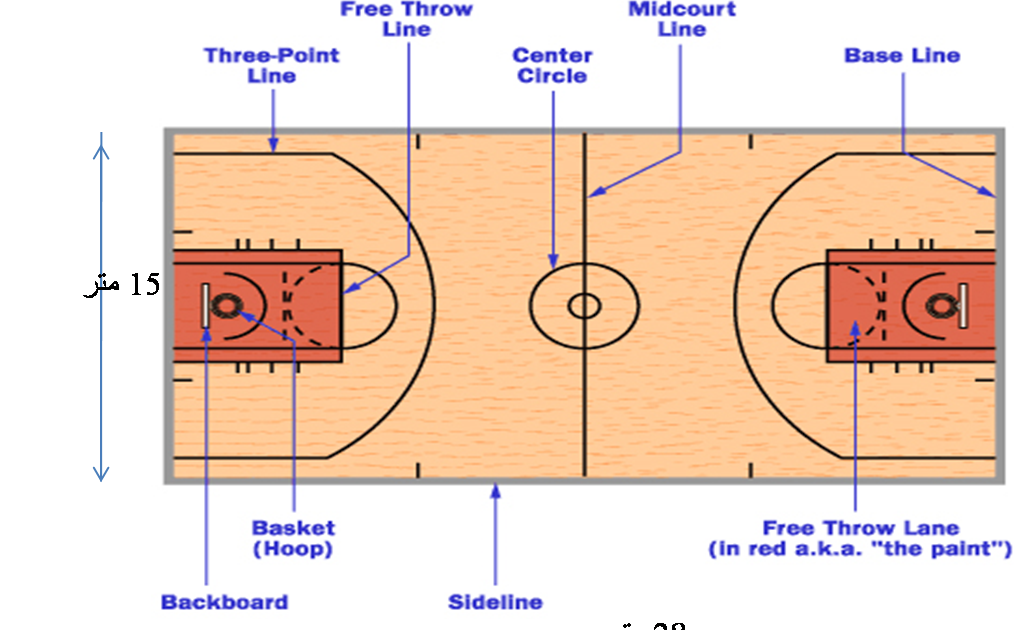

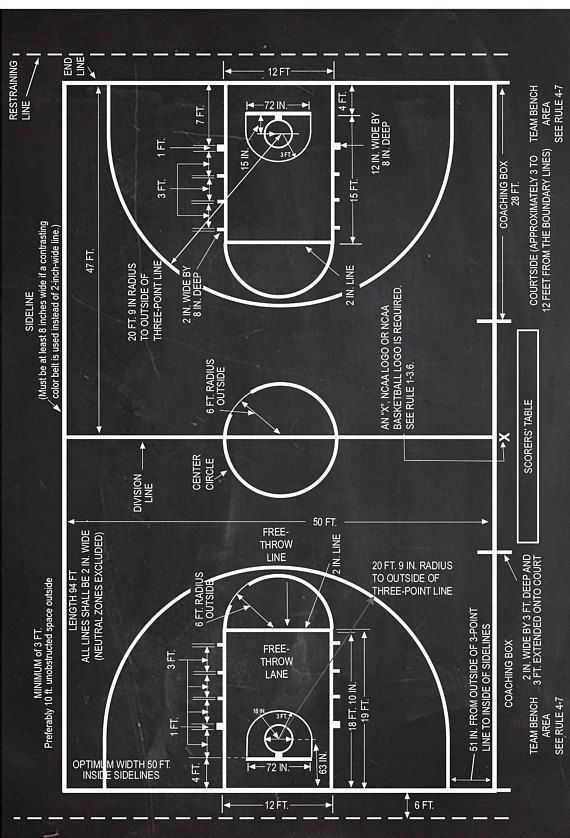

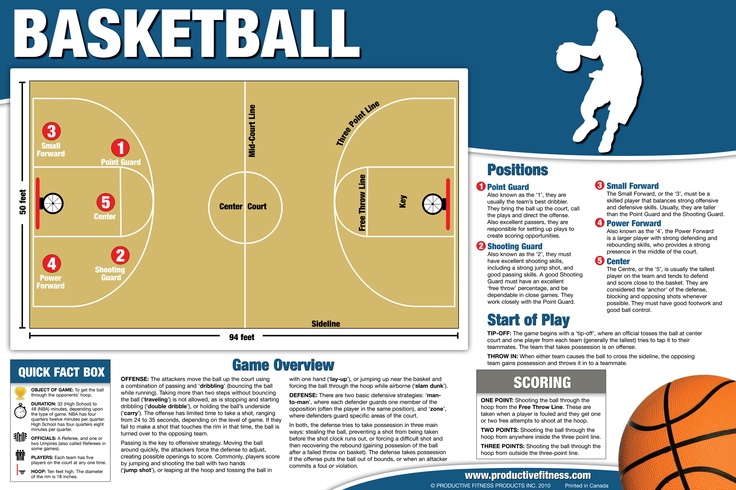

Though the distances differ between all levels of basketball, the 3-point line is universal. The NBA has a 22-foot 3-point line in the corners and a 23-foot, 9-inch line elsewhere. The WNBA and the international game plays with a 20-foot, 6-inch line. The NCAA men's game has a 20-foot, 9-inch line while the NCAA women and high schools have a 19-foot, 9-inch line.

Whereas size was a crucial factor in matchups in the past, the 3-point line gave smaller teams a great equalizer.

Even the post players get into the action--just not very often.

Shaquille O'Neal is 1-for-22 from 3-point range in his career, that one a humorous bank shot buzzer-beater. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar played half his pro career with no 3-point line and half of his career with it. He was 1-for-18 from behind the arc in his career.

More than anything, though, the 3-point line has made basketball a completely different experience for the fans--a more spread-out game with another level of energy that wasn't there before the 1960s.

"It keeps the game exciting, particularly at the college level," Elmore said. "There are times when people fall in love with it, and there's the adage that you live by it and you also die by it. When it's not incorporated properly and not utilized properly, it can hurt a team. But the advantage is to be able to stretch the floor."

How Far Is the 3 Point Line From The Hoop? Stats & Facts – Basketball Word!

To some, while watching basketball highlights or the game on T.V. it may appear that the 3 point line appears to be really far from the hoop. So if you are wondering, just how far is the three-point line is from the basketball hoop I have your answer.

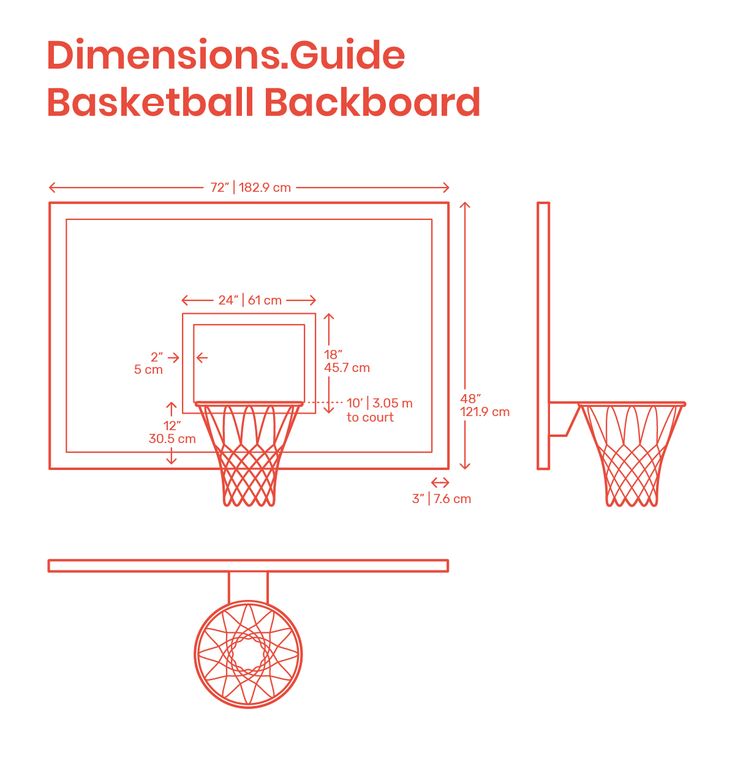

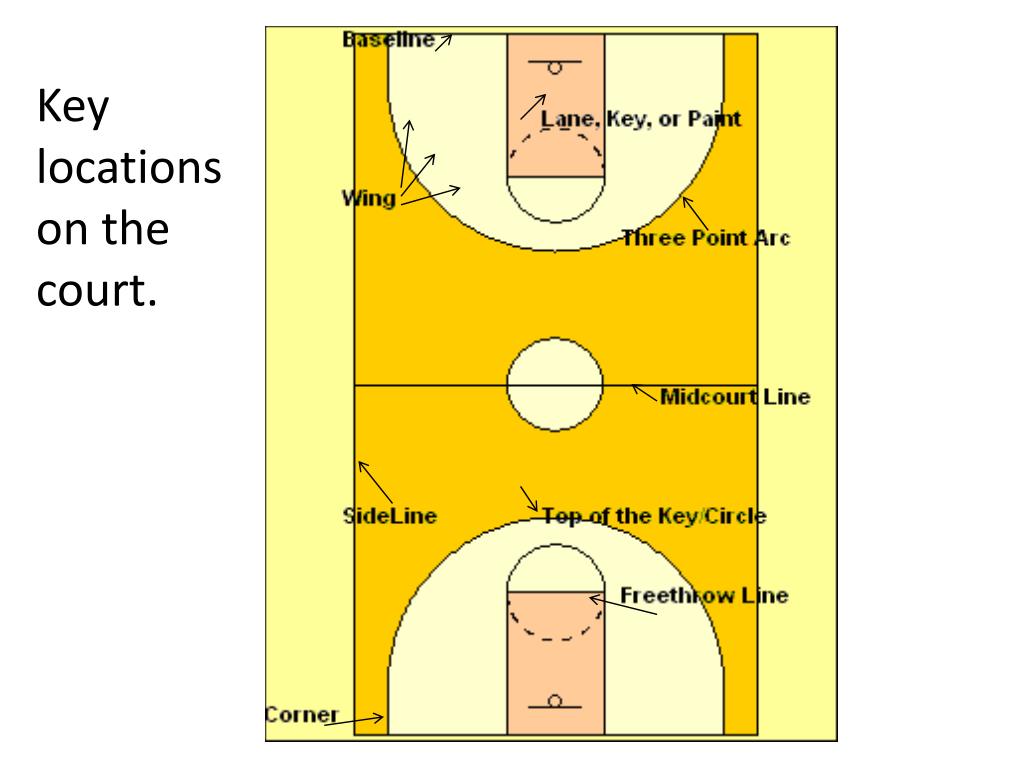

How far is the 3 point line from the hoop? The 3 point line to the hoop in highschool is 19 feet 9 inches (6.02 meters), in college it is 20 feet 9 inches (6.32 meters) and both the WNBA, as well as FIBA’s 3 point line, is 22 feet 2 inches (6.75 meters). With the NBA being the furthest out of any league measured at 23 feet 9 inches (7. 24 meters).

24 meters).

If you remember the 3 point line to be closer than what you remember it to be at some point in your life, don’t be alarmed it’s not a mandella effect, you are in fact correct. We will look at the history, stats, and facts of this line and how it’s changing the game.

If you are interested in checking out the best basketball equipment and accessories then you can find them by Clicking Here! The link will take you to Amazon.com

History Of The 3 Point Line

The 3 point line has been moved several times over the years and like I said if you remember it being closer, that was just the case in 1993/94 NBA season and for three seasons the NBA had a closer line. It is right now and before the move 23 ft 9 in (7.24 m) and at the corners 22 ft (6.71 m). They shorten to 22 ft (6.71 m) all the way around the basket.

Why the shortening, quite simply to induce more shots from the three, to increase more scoring and to add entertainment to the game. Which is sort of worked, numbers were up but not as much as the league thought they would be it actually took a number of years such as the third year where it really became apart of coaches plays. They then moved back the line to its original distance.

Which is sort of worked, numbers were up but not as much as the league thought they would be it actually took a number of years such as the third year where it really became apart of coaches plays. They then moved back the line to its original distance.

Some speculated that the NBA did this for Michael Jordan but the Chicago Bulls were hardly a 3 point shooting team. But a team like the New York Knicks benefited as John Starks during that time was the first player to break 200 threes in a single season.

3 Point Record-Breaking History

- Danny Ainge was the first to break 100 three-pointers in a single season crushing the existing record at the time of 92 with 148 made three’s in the 1987/88 season.

- John Starks of the New York Knicks was the first to break 200 in a season with 217 made shots in the 1994/95 NBA season.

- Ray Allen set the new record in the 2004/05 season with 269 made three’s.

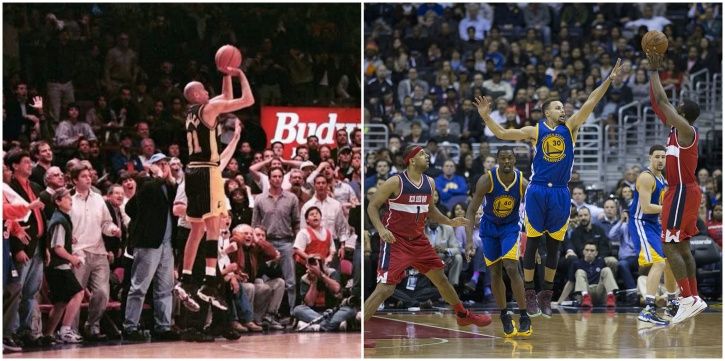

- The goat of the three-point shot Steph Curry made and broke his own record 3 times 272 in 2012/13, 286 in 2014/15, 324 in 2016/17, 354 in 2017/18 and 402 in 2015/16.

With more three’s made and attempted you would think that points per game for teams would go up also, but it hasn’t. It actually is roughly the same.

Was The 3-Point Line Invented By The NBA

The 3 point line was first introduced in the American Basketball League in 1961 for one and a half seasons before the league folded. The Eastern Professional Basketball League followed suit in 1963/64 season. It was Popularized by the American Basketball Association otherwise known as the A.B.A in which they introduced it in their first season as a league.

The ABA joined with the NBA merging into one league in 1976 while it wasn’t until the 1979/80 seasons of the NBA that the three-point line re-appeared in a league. It was predicated as a terrible shot choice and against a coach’s strategy that most teams shied away from the three.

The idea of the three-point line didn’t sit well with the players and coaches, most thought it was a gimmick or a ploy to draw more crowds. When a shot was taken, the crowd would be in awe as it went up and didn’t often make it in the hoop as shooting percentages were poor. But when it did go in the crowd erupted like a ferocious dunk in traffic.

When a shot was taken, the crowd would be in awe as it went up and didn’t often make it in the hoop as shooting percentages were poor. But when it did go in the crowd erupted like a ferocious dunk in traffic.

At the time the three-point line was 25 feet from the hoop that is further than it is now. That’s a foot further, so no wonder people were in aww when the shot went up.

Players and coaches had their reasons for not implementing it in their game plan, you have to remember that they have been practicing their whole lives without the three-point line, then out of nowhere, this is introduced. It changes everything.

The three-point line is more than just a line that you shoot from. Think about it, when you can’t see behind you and you’re on defense playing man to man with the ball, the three-point line can tell you where you are on the court in relation to the basket and how far away you are.

Quick Stat: James Harden averages 13 three-point attempts a game.

Coaches Distaste For The ThreeDuring the invention of the three-point line coaches built a system in their offense and prided on making sure the offense works. So it is obvious if you as a player that wanted playing time you would listen to the coach by any means necessary. For the coaches to all of a sudden make adjustments and incorporate the three into their system is not far fetched it just wasn’t something the coaches were interested in.

Many of the players and coaches assumed the three-point line wouldn’t last because many thought it was a gimmick. But for the fans, the new line was comparable to a slam dunk leaving the fans cheering and roaring when a shot was made.

At the time it could have been worded that the new line is something the league is going to try, so the teams might have thought not to invest too much into something when statistically it isn’t favorable and secondly it may not be there the next season.

When the ABA merged with the NBA any players who played in the ABA had a distinct advantage in shooting 3’s over those who didn’t, that is if you were given the green light by the coach to shoot three’s. That experience is huge in understanding the line and how it may affect the outcome of a game.

One or two three’s were shot per game and when the three went up, you can hear the crowds in awe as the ball was headed to the basket. If it went in the crowd when crazy like a game-winning shot. It was such a rare occasion that deserved its own recognition as a difficult shot.

Quick Stat: The Fewest shot per a team from the three-point line is the San Antonio Spurs at only 24 shots a game.

Lack of Strength Equals Less Accuracy

Now I am not saying players were not strong enough to shoot from 25 feet out back then, what I am saying is that it would have been difficult for players to shoot from that far when they played a whole game and their legs are tired. Accuracy wouldn’t have been exactly dead eye so to speak.

Accuracy wouldn’t have been exactly dead eye so to speak.

Players rarely worked out to improve strength with weights as many wives’ tale were told that weight lifting would affect a shooter’s shot. The opposite has been proven to be true, in fact, I always felt I shot much better when I was working out with weights as I felt all I had to do was aim and not worry about how much power I needed behind a shot.

Michael Jordan is a classic example of someone who worked out his upper body with weights on game day and we all know how that turned out. Obviously, if you have never done it before then it may be difficult at first. I feel you can never have to much strength in basketball as long as you continue to work on the skill tirelessly.

Too little strength becomes a problem, form on the shot is sacrificed and other parts of the shooting muscles have to sacrifice, and if you are a little tired good luck.

Quick Stat:

The Golden State Warriors in the 2017/18 season were 17th in the league in 3 pointers attempted by a team. They attempted 2370 shots and shot a record 40 percent from the field as a team.

They attempted 2370 shots and shot a record 40 percent from the field as a team.

How Three-Pointers Have Changed The Game Of Basketball?

I grew up lucky enough to watch Michael Jordan play the game of basketball in his prime back when the midrange was actually a thing. I remember working on my midrange game as much as possible because I felt it was the key to becoming a good player who can average 20 plus points a game.

I still believe this to this day even though shooting three-pointers has become more popular than Fortnite, so it seems. Believe it or not, I never practiced shooting 3s either, as I didn’t shoot a lot of them in games but when I did it didn’t feel like a three it just felt like another shot. Wherever the shot presented itself for me I would shoot.

Although I do not believe that now but wondered if I would have practiced shooting more three’s than I wonder how much better I would have been behind the arc. The game was not tailored at the time I was playing high school to shoot a lot of threes. It was more if you are open shoot the three.

It was more if you are open shoot the three.

We have all seen the impact one player can make in basketball. From Michael Jordan, Allen Iverson To Lebron James and now Steph Curry. They not only changed the culture but also the way the game is played. Young players craft their skill set modeling the fundamentals and style of these players.

One player who has made the greatest impact on the game of basketball in which it has changed the game entirely, comparing it to the last decade is definitely Stephen Curry. He ha single handily broke records including his own in the three-point shot and has shot with amazing accuracy.

It blows me away to see this guy hit threes with such difficulty. It reminds me of when of the story of runners that we’re told that running the mile in under 4 minutes was impossible. As soon as one runner did it everyone started to do it. This holds true in my opinion with the three-point shot, it is like a layup to these players.

Teams are shooting more 3s than ever. I was watching the Houston Rockets play their second game of the season and they took more than 50 three-pointers in one game. As of the 2019/20 season Houston is averaging almost 50 threes a game.

I was watching the Houston Rockets play their second game of the season and they took more than 50 three-pointers in one game. As of the 2019/20 season Houston is averaging almost 50 threes a game.

The crazy thing is I do not see this shot selection slowing down. I strongly believe although I don’t have statistics to back me that players are shooting the three with more efficiency. Heck, the Centers are shooting three and doing it well.

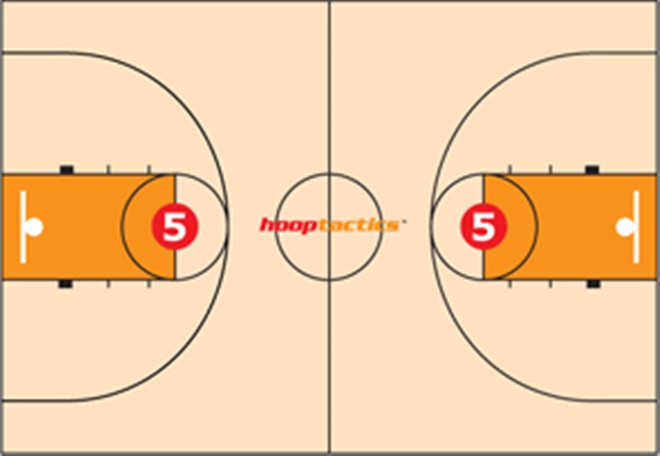

There is some strategy that goes along with it, the center stays out at the three-point line, the center has now opened up the middle for penetration. Bringing out the shot blocker away from the hoop. These centers are open when their defender leaves to help on defense.

The ball goes to the center for a shot. Many centers develop a three-point shot when they get into the league as their success in getting into the league was based on playing the center not shooting 3s. Centers as of now take a couple of threes a game. But in the near future, I wonder if we can see a center lead the league in three-point efficiency.

Quick Stat:

The Houston Rockets have lead the league in 3 pointers made with 14 to 16 three’s in the last 3 seasons.

Every Player Loves The Three

As millions of kids around the world want to shoot the ball like Stephen Curry, the problem is that they are sacrificing their form just to get the ball to the rim. Young kids are playing with basketballs that are too heavy and big when they should focus on the basketball sizes for their age.

The three-pointer is more popular then it has ever been, it is completely normal to see more free throws attempts than midrange jumpers, while the 3 point shot and the layup/dunk dominate the shot selection.

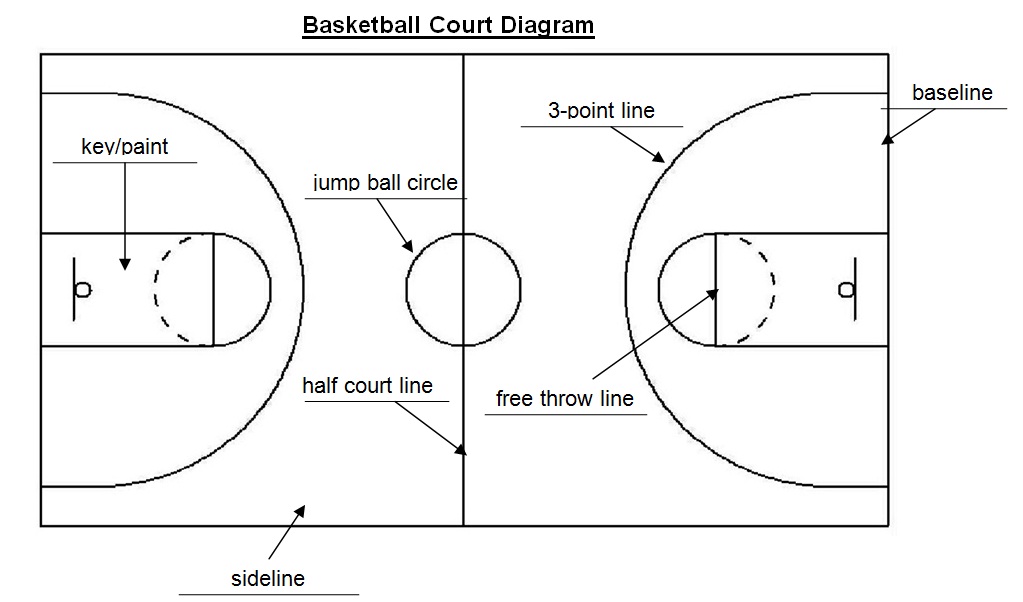

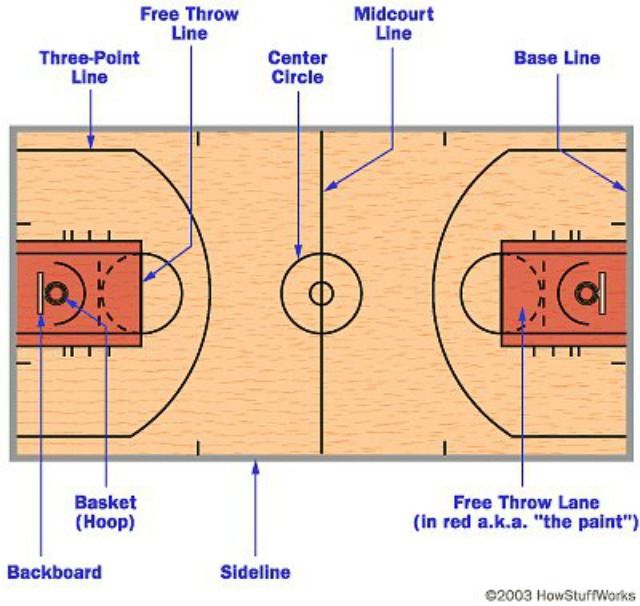

In today’s game, we can see the 3 point line and use it as a guide on defense to determine where you are on the court relative to the basket. If no lines were there you would have to look back to see where you are in relation to the basket.

If they are able to shoot the three you want to be above the three-point line, If they are more of a penetrator, you will want to stay just on or just underneath it. I believe the three-point line helped every player play better defense. Could you imagine if there was no line, and you are on the wing guarding a good scorer, it would be hard to determine how far away you are from the basket and the angle you are at.

4 Point Line Or Move The Three Further

There has been a lot of talk throughout the past couple of years of moving the three-point line further away from the basket as the NBA has changed dramatically with it’s shot selection. How far back no one knows but this is something the NBA always looks into. Is the amount of threes taken and made ruining the NBA game, if they thought it was I think they would push the line further, such as when they moved the line closer to in the 1993/94 season.

Larry Bird was once quoted in an interview and he is as old school as they get saying the game has to move with the times and he thinks one day were going to need a 4 point line. Where are we going to put that line, players are already shooting 5 feet away from the line with such efficiency.

Where are we going to put that line, players are already shooting 5 feet away from the line with such efficiency.

In the end, I believe the game is changing at a rapid rate, the role of the big man has changed completely while the three-point shot attempts have also increased. The side effect is quicker shots faster game and more points on the board.

That concludes the article, please check back as I update the site frequently.

Further Readings:

- How To Become A Better Shooter In Basketball: Ultimate Guide

- When Are Baskets Worth 3-points?

- How To Improve Shooting Accuracy In Basketball? A Different Approach

90,000 Three-pointers are killing basketball. We need to do something about it, immediately - Bank shot - Blogs

Basketball Greta Thunberg warns.

Translation of key points from the book Kirk Goldsbury's Stretch Era: A Visual Tour of the Modern NBA

It's undeniable that the advent of the three-point line on the basketball court has completely changed the game. Exactly 40 years have passed since then - the NBA has lived longer with an arc than without an arc.

Exactly 40 years have passed since then - the NBA has lived longer with an arc than without an arc.

With the exception of a short three-year stretch in the 90s, the three-point line has remained roughly the same. Interestingly, the modern design of the court has existed for much longer than any of its previous configurations.

The problem is that for many of us three-pointers are losing their appeal. Snipers are too good and feel too at ease, and long-range attempts are becoming more and more numerous.

Here's an insane number: in the 2017/18 season, the NBA made 25,807 three-point shots. This is more than in the entire 80s. Between 1979 and 89/90 seasons in the NBA put 23,871 three-pointers.

Throughout its history, the league has shown an impressive willingness to change the rules and layout of the court to make the game more varied and interesting.

In 1947, when the league banned zone defense, one of the main defensive tactics disappeared.

In 1950, to get rid of rudeness and unsportsmanlike fouls, the league introduced dropped balls after every free kick scored in the last three minutes—rather than simply giving possession to the team that broke the rules.

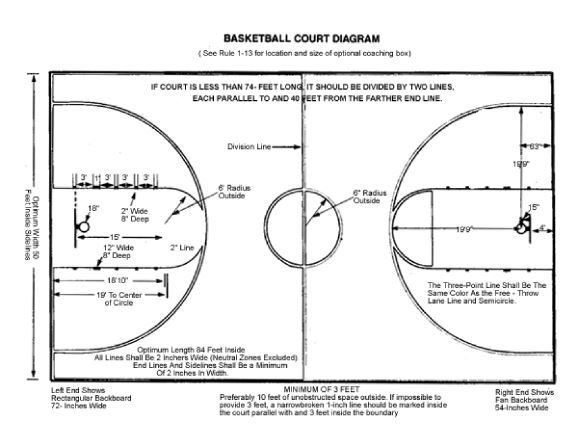

In 1951, the so-called Mikan rule changed the face of the basketball court by doubling the three-second zone from 6 to 12 feet to reduce George Mikan's unprecedented dominance.

13 years later, in 1964, the league extended the 3 second again to 16 feet, this time to influence Wilt Chamberlain's dominance.

And now, 55 years later, it is still the same size.

These two "extensions" are interesting to look at for several reasons.

First, they show that the league has always changed the layout so that one particular element or one particular style of play does not become dominant . NBA basketball is constantly changing, and while some of the transformations have been natural, some have been engineered by generations of legislators in the NBA office. Like the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, the building is already incredible, but continues to evolve all the time: professional basketball is never perceived as a finished product.

Second, 's two decisions to expand the three-second time limit show that the league's most daring rule changes were aimed at making life harder for the big ones - and making life easier for the "little ones" . Looking at modern basketball, where there are fewer and fewer real centers and power forwards, it is very difficult to imagine that once it was the “big” ones who were the main participants in this show, and the small players played limited roles.

Between 1946 and 2018, the NBA consistently changed the rules to move away from the tough game of the "big" in favor of the perimeter-oriented game of the small. And while you can see the small five as a product of analytical genius, the truth is that modern aesthetics and trends in professional basketball have little to do with analytics, but seem to be the culmination of a 70-year prejudice against the big. The three-point arc is just one example.

George Mikan revolutionized basketball. He became an example for the next generations of the NBA and laid the aesthetic foundations for the entire sport. In the next 30 years, basketball was dominated by a whole bunch of centers who took a cue from the trailblazer, rushed into the low post and stormed the shield. Guys like Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain were champions and MVPs, the teams with the best centers had the best chance of winning. The league's early superstars were almost all shaped like Mikan, and the league continued to influence their play. Wilt Chamberlain was so athletic that he could immediately shift the misses of the partners into the ring - and then the league introduced a rule that it was forbidden to touch the ball before it left the cylinder of the ring. At 19The 64th was followed by an expansion of "paint".

In the next 30 years, basketball was dominated by a whole bunch of centers who took a cue from the trailblazer, rushed into the low post and stormed the shield. Guys like Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain were champions and MVPs, the teams with the best centers had the best chance of winning. The league's early superstars were almost all shaped like Mikan, and the league continued to influence their play. Wilt Chamberlain was so athletic that he could immediately shift the misses of the partners into the ring - and then the league introduced a rule that it was forbidden to touch the ball before it left the cylinder of the ring. At 19The 64th was followed by an expansion of "paint".

The league came up with the Most Valuable Player award in 1955, after which the centers began to win it almost every year. Of the first 24 trophy winners, forwards took only two or three (depending on who you think Bob McAdoo is), and defensemen only two. Centers - 19 or 20. You understand what I want to say. It was the big league. After Maikan, it became clear that the center is the most valuable position on the court.

It was the big league. After Maikan, it became clear that the center is the most valuable position on the court.

But Maikan didn't finish changing basketball.

In the 1960s he did it again, now as a commission agent.

In 1967, he became the first commissioner for the ABA, a new league that tried to compete with the NBA. To achieve this goal, he had to come up with all sorts of tricks that would attract the attention of fans and make basketball more attractive. He got a few. First of all, he added a red-white-blue ball - he thought that such a ball would look more spectacular than the orange-brown version that was used in the NBA and NCAA. The kids really liked it a lot. But that wasn't enough. We needed another crazy idea that would make the game more unpredictable. And so he revived the idea of the "three-point shot," which was first used in the American Basketball League in early 1919 without much success.60s.

What is the American Basketball League? This league was born in 1961 and lasted only two seasons. Her commissioner was Abe Saperstein, a man remembered not for running the failed ABL but for starting the Harlem Globetrotters. Saperstein was half showman, half basketball visionary.

Her commissioner was Abe Saperstein, a man remembered not for running the failed ABL but for starting the Harlem Globetrotters. Saperstein was half showman, half basketball visionary.

In the early 60s, John F. Kennedy was president, the space race between the USSR and the USA was just beginning, and the Americans did not leave their TV sets and followed the Cuban Missile Crisis. Baseball was then the most popular sport in the country, and the most popular athlete was Roger Maris. He captivated fans across America by breaking all records for the number of home runs. In the fall of '61, Maris broke Babe Ruth's all-time record when he hit his 61st home run of the season.

Home runs were by far the most exciting element of America's favorite game. There was something so magical about that endless flight of the ball that made baseball fans jump up and down. Those few seconds of flight, everyone in the stadium - fans, players, commentators and coaches - were waiting to see where this rocket would land. Home runs not only created tension and attention, they also had a big impact on the game - it's the fastest way to "run" in baseball. It was the best in American sports.

Home runs not only created tension and attention, they also had a big impact on the game - it's the fastest way to "run" in baseball. It was the best in American sports.

So it's no coincidence that Abe Saperstein's revolutionary idea came about in 1961 in a country that was going crazy with rockets, long-range bombs, home runs and gunshots going around the world.

Saperstein asked himself what would be home runs in basketball? What would it look like?

He came up with an insane variation on the "home run throw" that would be similar to what Maris did: the longest shot and the fastest way to score. Also keep in mind that during Mikan-Russell—the first 20 years of the NBA—most shots were made close to the rim. It made no sense to throw from a distance, as such throws were more difficult and less effective. Wilt Chamberlain rarely threw from three meters, let alone 6.5.

Saperstein consulted with the players and coaches and agreed with them to create a three-point arc. Where did he place it? Exactly where you see her today. 22 feet in the corners, 23.75 feet in the rest of the area. Madness, right? This happened almost 60 years ago. What are the chances that the optimal distance for the arc during Chamberlain is the optimal distance during Steph Curry's time?

Where did he place it? Exactly where you see her today. 22 feet in the corners, 23.75 feet in the rest of the area. Madness, right? This happened almost 60 years ago. What are the chances that the optimal distance for the arc during Chamberlain is the optimal distance during Steph Curry's time?

And yet, if not for Mikan and the ABA, most likely the idea of a three-point arc was born and would have died along with the ABL, which lived for two seasons. The ABA and the three-point shot changed the history of basketball forever. Alex Hannam, who led Philadelphia to an NBA title in 66/67 and Oakland to an ABA title in 68/69, immediately noted the influence of the line and how it opens up the court: “In the NBA, we just hammered the central zone and forced the teams to attack from afar. No one was going to keep anyone five meters from the basket, but the threat of a three-pointer changed everything. Someone starts to hit from a distance and score not two, but three points, and the coaches are forced to change the strategy - and defense. No other rule made the game so open, so fun .”

No other rule made the game so open, so fun .”

Hannam was right. The Saperstein line didn't just give basketball home runs, it opened up the entire court. She made basketball less contact, helped to get away from the flea market. Passes were now given over longer distances, throws from a distance became more spectacular. The ball was more often in the air, moved more. Just like the players themselves. All of a sudden there was more room for players to show off and more ways to score. The ABA has taken Saperstein's vision and enriched basketball.

Largely because of the three-point arc, the ABA immediately showed differences between themselves and the NBA. The arc affected every possession, even those that didn't make it to 3-pointers. Players ran around the court a lot more, ABA games were more fun, they gave the attack more room to shine, and they played at a faster pace. The NBA remained the more successful league and retained all the talented players, but compared to the ABA, it looked conservative and rigid. Hardcore backboard play still dominated there, and the philosophical differences between the leagues only deepened as the decade progressed, until the NBA was left with no choice but to bring the 3-point line to its courts as well.

Hardcore backboard play still dominated there, and the philosophical differences between the leagues only deepened as the decade progressed, until the NBA was left with no choice but to bring the 3-point line to its courts as well.

In 1976 the leagues merged. The NBA accepted four teams from the ABA, the other three closed. A few years later, despite the protests of Celtics president Red Auerbach, the NBA added a three-point arc and placed it exactly where Saperstein intended it to be, 22 feet in the corners and 23.75 feet in the arc.

There she remains to this day.

Maybe it's time for a change. Mikan once brought the 3-point line into the ABA to "give the little players a chance", but now the big players - Mikan's heirs - need that chance. In fact, in 2018, big players are less visible than small ones before the introduction of the arc. Curiously, centers weren't on the court during major episodes of the past decade. For example, in the 2016 finals, Cleveland and Golden State rarely used centers: both Andrew Bogut and Timofey Mozgov almost never went to the floor. And in the main series of 2018 - the series between the Rockets and Golden State - Houston missed from behind the arc in the seventh game, when they threw 7 of 44. Missed three-pointers are now the main aesthetics of the NBA, and all analytics boil down to the thesis “hit or miss” .

And in the main series of 2018 - the series between the Rockets and Golden State - Houston missed from behind the arc in the seventh game, when they threw 7 of 44. Missed three-pointers are now the main aesthetics of the NBA, and all analytics boil down to the thesis “hit or miss” .

Over the past decade, shooting from behind the arc has become the most important skill in the game. Snipers have taken over basketball, and the only ones left in the NBA are the big ones who can shoot—and defend—on the perimeter. Guys like Bogut and Mozgov can do neither, and therefore their value is lower than ever. It so happened that by 2018, Bogut, a huge Australian center, the first number in the 2005 draft and one of the key characters for the rise of the Warriors, was out of the NBA altogether, and Mozgov, at the age of 33, did not succeed much more. Although the Russian big man signed a huge contract with the Lakers in the summer of 2016, he spent several years as an outcast who was transferred from team to team and barely appeared on the court for Brooklyn in the 2017-18 season.

In parallel with the major changes of the 50s and 60s that neutralized the post game and introduced the three-point arc, the league also made other subterfuges to help reduce the value of the traditional bigs. At the same time, while in the early years the development of the NBA constantly changed the rules and moved the markings, today's NBA is in many ways reminiscent of the modern Congress - it absolutely cannot not only introduce, but even propose at least some change.

Now this is a league where stretchy skinny guys like Ryan Anderson and Channing Fry are more valuable than stupid dinosaurs like Al Jefferson trying to attack from the low left post. This is a league where a guy like DeMarcus Cousins, arguably the most physically intimidating man in basketball today, throws as many 3-pointers as Reggie Miller once did. In the 2017/18 season, Cousins made 6.1 shots per game - Miller reached this mark only once in his 18-year career.

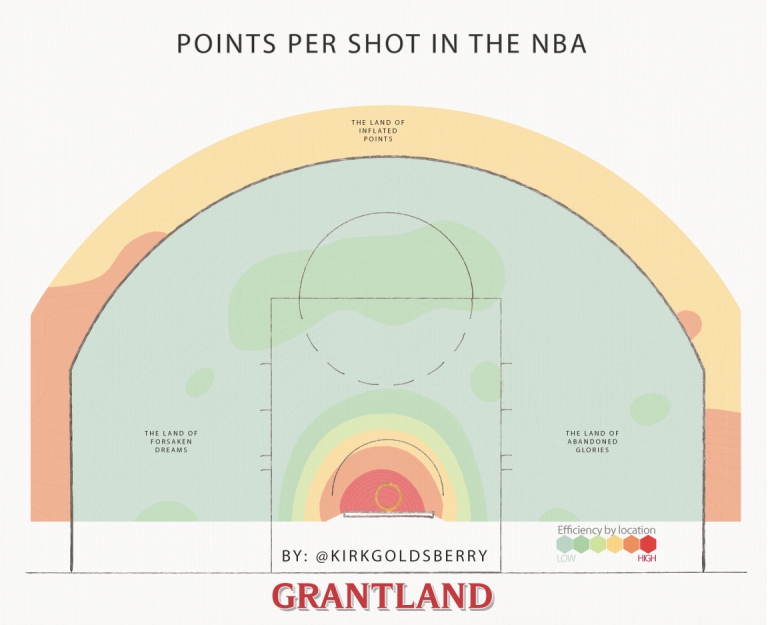

The two three-second extensions that devalued the power of the big ones and pushed them into the medium throw zone are just the first blow to those whose main contribution is the game in the post. The second hit is the addition of the 3-point line, which brings a circus trick of extra value to the long shot. This stunning combination knocked out the giants and sent them to analytically acceptable reservations near the ring and beyond the arc. The new markings left for the traditional "big" zones that people like Daryl Morey despise - places where you can't break through for a good attack from under the basket and yet far from all the perks offered beyond the three-point arc.

The second hit is the addition of the 3-point line, which brings a circus trick of extra value to the long shot. This stunning combination knocked out the giants and sent them to analytically acceptable reservations near the ring and beyond the arc. The new markings left for the traditional "big" zones that people like Daryl Morey despise - places where you can't break through for a good attack from under the basket and yet far from all the perks offered beyond the three-point arc.

Over the past decades, the "big" and their mid-range attacks have become - not too surprisingly - "less effective". At the same time, both the team's tactics and the work of management are more focused on giving the ball less to the mustache and looking for a sniper on the arc much more often.

While the extensions to the 3-second deliberately reduced the value of underfield play - and the big ones - the arc did exactly the opposite for snipers: it increased the value of those who could shoot 3-pointers. An incredible attempt back to the ring, a hook through Joel Embiid's outstretched arms is only two points, and another open throw from a take-throw situation from Danny Green or Trevor Ariza is three points. For anyone who has ever played the NBA Jam, it should be obvious that the number of points scored no longer correlates with the difficulty of the throw.

An incredible attempt back to the ring, a hook through Joel Embiid's outstretched arms is only two points, and another open throw from a take-throw situation from Danny Green or Trevor Ariza is three points. For anyone who has ever played the NBA Jam, it should be obvious that the number of points scored no longer correlates with the difficulty of the throw.

The pursuit of efficiency is nothing new. It is clear that both Mikan and Chamberlain were extremely effective players for their time. But the modern path to efficiency is dictated by the rules and threatens a variety of play in a way we haven't seen since Mikan and Chamberlain. Today, harnessing the dragon of efficiency means making the most of three-pointers, which leaves vast areas of scoring ground to waste. As in ancient times, a new, albeit different, kind of one-dimensional attack has hit the entire league.

This is perhaps the main idea of the modern era: successive rule changes have produced a generation of player coaches for whom the three-point line has redefined the basic economic geography that defines the fundamental principles of basketball. According to these principles, "greatness" and maximum contracts are reserved for players who are able to consistently perform the most impressive tasks at the highest level. But as the 3-pointer becomes one of the biggest and most visible options on the floor, people who can do it in high volumes are becoming "great" even though it's not really a great skill.

According to these principles, "greatness" and maximum contracts are reserved for players who are able to consistently perform the most impressive tasks at the highest level. But as the 3-pointer becomes one of the biggest and most visible options on the floor, people who can do it in high volumes are becoming "great" even though it's not really a great skill.

As teams, players, and coaches find ways to shoot more and more 3-pointers, the very nature of the game is changing and taking away something important—namely, links to the past. 90,005 90,002 During the '79/80 season, the Rockets made 4.6 3-pointers and 86.8 2-pointers per game. 90,005 90,002 In 2017-18, the Rockets made 42.3 three-pointers and 41.9 two-pointers per game.

Today's aesthetic is built around three interrelated trends: positional versatility, long-range shooting, and isolation.

As Draymond Green became the dominant defensive figure for Golden State, the Warriors adopted a new defensive philosophy and began to trade on every screen—which also reduced the value of screening. Most of their players can defend in multiple positions, but there are a few weak links in Golden State's defense. As Houston demonstrated, all of these defensive exchanges can be exploited by the opposition. For example, the Rockets weakened the Warriors' defense by forcing them to trade early in the attack so that Steph Curry would stay against James Harden. Again and again, Harden played "isolation" against Curry, and the rest of the Rockets created space for him. The whole series turned into a one-on-one game between Harden and Curry, with the other eight guys just watching her from their best positions.

Most of their players can defend in multiple positions, but there are a few weak links in Golden State's defense. As Houston demonstrated, all of these defensive exchanges can be exploited by the opposition. For example, the Rockets weakened the Warriors' defense by forcing them to trade early in the attack so that Steph Curry would stay against James Harden. Again and again, Harden played "isolation" against Curry, and the rest of the Rockets created space for him. The whole series turned into a one-on-one game between Harden and Curry, with the other eight guys just watching her from their best positions.

Houston coach Mike D'Antoni defended this strategy and stressed that it worked.

“Everyone's like, 'Oh my god, they're playing isolation! That's all they do." No, that's not all, he said. “That's what we do best. We score points 60 percent of the time. And everyone's like, “Oh my God, they don't play pass. Everyone just stands there." Truth? Have you ever seen us play? This is exactly how we operate. It's our nature, it's what we're really good at."

It's our nature, it's what we're really good at."

He was right. These "isolations" not only worked, they were also a natural tactical response to the Warriors' strategy of trading everything on defense. This strategy was only made possible by rule changes and regular refereeing errors that greatly reduced the positional diversity and value of the traditional NBA Bigs.

One of the biggest reasons Green and the Warriors can trade is because their opponents don't have the ability to penalize them for using a miniature center. Roughly speaking, we have reached the point where the optimal one-on-one advantage is achieved between a small player and a slow defender who is forced to go to the perimeter. This is a very strong departure from the norms that created basketball in the first place. For most of the history of the NBA, the optimal one-on-one advantage was achieved under the backboard, where the offensive team would trade a powerful big player against a small, weak defender. Maikan, Russell, Karim, Shaq or whatever - they all destroyed under the shield. But nobody else does that.

Maikan, Russell, Karim, Shaq or whatever - they all destroyed under the shield. But nobody else does that.

Houston gained a huge advantage every time Harden was left alone against weak defensemen. That is why they used this variant more than 150 times throughout the series. Do you know what they didn't do? They didn't try to take advantage of the shield. Never. Rockets center Clint Capela, this giant dunk machine, flirted in the post 6 times in the entire playoffs and never in a series against Golden State. Why? And why should he? The numbers are pretty clear: post-ups are dumb, it's much more efficient to seek "isolation" for Harden than to give the ball to Capele. During the regular season, Capela had 55 post situations, of which he averaged 0.92 points. Figovato. At the same time, Harden used 894 "isolations", which brought an average of 1.15 points.

Lest you think Capela's lack of efficiency is the problem, consider the following. Among the seven players who played more than 500 mustaches in 17/18, Carl-Anthony Towns was the top performer, averaging 1. 05 points. That's good, but it doesn't come close to Harden's 1.15-point isolations or the relative efficiency of even a league-average 1.07 three-pointer. In other words, an average 3-pointer thrown by, say, Trevor Ariza, Ryan Anderson, and PJ Tucker is a better option than a post-up shot by the best post-up artist in the league. No wonder, then, that the game under the shield is dying, and the cause of death lies in inefficiency, in the most terrible disease of our era. Look: in the 2013/14 season, 22 NBA players flirted under the shield at least 500 times. By the 2017/18 season, only eight of them remained. In the 2013/14 season, five players entered the post at least 1,000 times, by the 2017/18 season, only one remained - LaMarcus Aldridge.

05 points. That's good, but it doesn't come close to Harden's 1.15-point isolations or the relative efficiency of even a league-average 1.07 three-pointer. In other words, an average 3-pointer thrown by, say, Trevor Ariza, Ryan Anderson, and PJ Tucker is a better option than a post-up shot by the best post-up artist in the league. No wonder, then, that the game under the shield is dying, and the cause of death lies in inefficiency, in the most terrible disease of our era. Look: in the 2013/14 season, 22 NBA players flirted under the shield at least 500 times. By the 2017/18 season, only eight of them remained. In the 2013/14 season, five players entered the post at least 1,000 times, by the 2017/18 season, only one remained - LaMarcus Aldridge.

While the league has essentially fought the bigs at the legislative level since Mikan, maybe - just maybe - during Curry, Morey and endless lockdowns and 3-pointers after receiving it, it's time to move on from that. Perhaps since we're in an era where centers and shield play are close to extinction, we need to resort to our own version of the Endangered Species Act and roll a couple of dice to the giants. Except during the biggest stylistic shift in basketball history, the league suddenly does nothing and instead maintains all the same conservative trends that led to the current state of affairs in the first place. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the NBA is more popular than ever. Perhaps because only such old grumblers like me are unhappy with the rise of the three-pointer and the monotonous monotony of attacks.

Except during the biggest stylistic shift in basketball history, the league suddenly does nothing and instead maintains all the same conservative trends that led to the current state of affairs in the first place. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the NBA is more popular than ever. Perhaps because only such old grumblers like me are unhappy with the rise of the three-pointer and the monotonous monotony of attacks.

Decades after Saperstein and Mikan, three-point shots determine the outcome of more and more matches. Revisit the ending of Game 7 of the 2016 Historic Finals. At the key moment of the main meeting of the decade, Golden State and Cleveland simply exchanged three-pointers. In the two-point shot zone, nothing happened at all. The pendulum has swung from the rim to the 3-point arc, and for some of us, the average NBA possession, in which three guys just stomp around the corners or around the edges, loses its magic.

Saperstein's "home run" has become so common that few people jump from their seats. In 2017, the Houston Astros became champions - they also hit the most home runs, averaging 1.47 per game. Their 2018 NBA counterparts, the Rockets, led the NBA in 3-pointers, averaging 42.3 per game. Once upon a time, three-pointers gave novelty, for half you could see only a few attempts, now they are realized on average every minute. Are three-pointers still amazing when they come in every minute?

In 2017, the Houston Astros became champions - they also hit the most home runs, averaging 1.47 per game. Their 2018 NBA counterparts, the Rockets, led the NBA in 3-pointers, averaging 42.3 per game. Once upon a time, three-pointers gave novelty, for half you could see only a few attempts, now they are realized on average every minute. Are three-pointers still amazing when they come in every minute?

A rise in three-pointers means a decrease in two-pointers. Some of us lack the momentum and athleticism needed to score inside the arc. For example, I would like to see fewer three-pointers from PJ Tucker and more deflected shots from Michael Jordan, dreamshakes from Hakim and hooks from Abdul-Jabbar.

An increasingly monotonous aesthetic correlates less and less with the geniuses who shape the strategy of the game, and more and more with the fact that the league fell asleep at the wheel while the bus slowly moves into a uniform ditch of endless three-pointers . In 2019, a long-range shot after a pass is about as unique and exciting as playing under the shield in 1978. The same factors that forced the expansion of the three-second in the 50-5 and 60s should be the impetus for new changes: aesthetics, tactical diversity and entertainment aspect.

In 2019, a long-range shot after a pass is about as unique and exciting as playing under the shield in 1978. The same factors that forced the expansion of the three-second in the 50-5 and 60s should be the impetus for new changes: aesthetics, tactical diversity and entertainment aspect.

Call me old fashioned, but my favorite teams are the Heat and Spurs of the 2010s. For me, the movement of the ball and the tactical variety of the 2013 and 2014 finals are priceless. Those series featured future Hall of Famers Tony Parker, Tim Duncan, LeBron James and Dwyane Wade—phenomenal players who reached the highest level and won the Final Series MVP title and did so without three-pointers. Their greatness declared itself within the arc. Those teams are not that in every attack they tried to smuggle the ball under the shield. The ball was moving at a crazy speed, and each team had amazing long-range artillery specialists Danny Green, Shane Battier and Mike Miller. Those matches were great.

But here's a paradoxical thought for you: if we like the way basketball looks this decade, we should advocate for rule changes that would slow down or even limit the league's increasing craze for 3-pointers.

We must support change that develops the variety of aesthetics and athleticism that has been at the heart of basketball since the days of Bob Cousy and Bill Russell.

But what can be changed?

Every time the NBA has faced an aesthetic crisis, it has changed the rules to adjust the visuals of basketball.

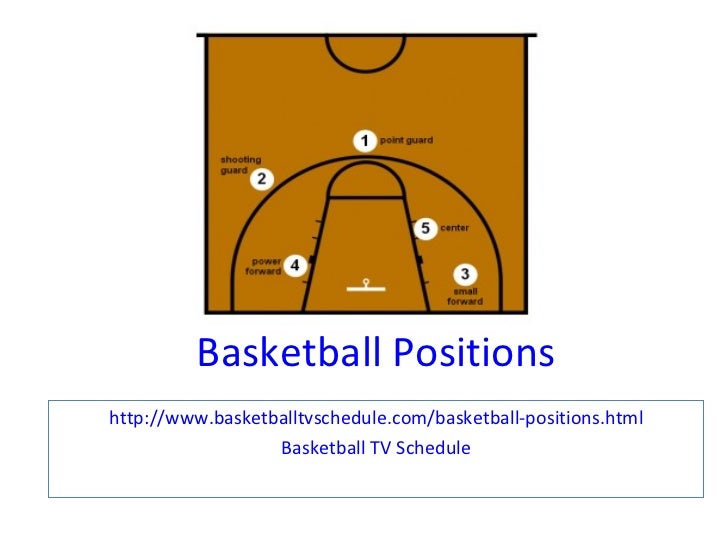

Basketball is at its best when different types of players can perform differently. Since the start of the game, five different positions have emerged organically: point guards, shooting guards, small forwards, power forwards and centers. One way basketball protectionism is to keep each of these unique species alive is to create a balanced version of basketball in which each is important in its own way.

There is no such vision in the modern NBA. Centers are disappearing, wingers are becoming power forwards or, more accurately, stretching fourths, and backboarding, once the dominant offensive tactic, is heading in the same direction as MySpace. The average NBA game consists of 60 three-pointers (the number is rising) and less than 20 post-shots (the number is falling) .

Centers are disappearing, wingers are becoming power forwards or, more accurately, stretching fourths, and backboarding, once the dominant offensive tactic, is heading in the same direction as MySpace. The average NBA game consists of 60 three-pointers (the number is rising) and less than 20 post-shots (the number is falling) .

So what options do we have?

Transfer line!

The League impacted Mikan and Chamberlain's prime years with a major rule change designed to dampen their offensive power. In both cases, the league made changes not only to reduce the effectiveness of their play in the post, but also to ensure that they attacked less often. The changes were connected not only with dominance, but also with aesthetic considerations.

Based on this, the league should try to transform the shape and location of the three-point arc.

First of all, why is the line where Abe Saperstein placed it in 1961, almost 60 years ago? Then only a few players could get from there, today almost all of them.

Move it 7.5 meters away from the ring?

The simplest change is to move the archwire.

For three seasons in the 90s, the league moved the three-point line closer as an experiment. By the end of this period - by season-1996/97 - 3-pointers made up 21% of field goals. The next season, the league moved the arc back to its original position, half a meter back, presumably because the number was too high. The figure has dropped to 16 percent.

We can also learn from the WNBA. The league moved the arc to a distance of 0.5 meters, which corresponds to the distance provided for by FIBA rules. The results were immediate: in the previous two seasons, 25.3% of field goals were converted from behind the arc, the league as a whole sold 35.2% of such shots. When the arc was pushed back, these figures fell to 21.5% and 32.7%, respectively.

In both cases, this affected the effectiveness and the frequency of long attempts, and thus returned the emphasis to two-point attacks. If the NBA moves the arc by 7.5 meters, it will likely bring about similar changes. During the 2013/14 regular season, NBA players threw 52,000 three-pointers. More than 25 thousand - from a distance of more than 7.5 meters. In general, such throws were realized with an accuracy of 34.5 percent, compared with 38.4% from a distance closer than 7.5 meters .

If the NBA moves the arc by 7.5 meters, it will likely bring about similar changes. During the 2013/14 regular season, NBA players threw 52,000 three-pointers. More than 25 thousand - from a distance of more than 7.5 meters. In general, such throws were realized with an accuracy of 34.5 percent, compared with 38.4% from a distance closer than 7.5 meters .

As you can see from this graph, the number of three-pointers went down only when the league moved the arc back to its original position. It is likely that something similar will happen again. The retries will go down. Efficiency will go down. The value of snipers will go down. Two-pointers will again be significant and tactically in demand. The players of the post will return respect.

The good thing is that we can now use all of these examples to predict how moving the NBA line 7.5 meters will affect shooting behavior in the NBA. It’s bad that a distance of 7.5 meters is still a subjective decision. Why 7.5? Why not 7.5? Why not 8?

Why 7.5? Why not 7.5? Why not 8?

Why not move the arc to match the analysis we have?

Here's an interesting fact: on average, a field goal scores almost exactly one point. What an amazing analytical coincidence!

The invention of the three-point arc made 33.33% the magic number in the NBA. Anyone who can convert a third of his long shots will average one point per possession. This is the same as converting half of two-point attempts. But over time, sharpshooters have progressed and come to realize 36%, and the best of them regularly put 40%. This is the same as converting 60% of 2-pointers .

A small increase in efficiency and a huge increase in the number of players that can deliver that efficiency at high volumes are the two defining factors of the new era.

These bursts of efficiency may seem small to individual players, but at the league level they are amazing. When shooters in general put 36% of three-pointers, the attitude towards such shots changes. There was a time when 3-pointers weren't the best shot for most players in the league. It's long gone. Now we have data that helps to determine with great accuracy where exactly snipers attack from better. And on the basis of such data, you need to determine the distance by which you need to move the three-point line. We need to figure out where the league is going to hit exactly one-third of all 3-point attempts.

There was a time when 3-pointers weren't the best shot for most players in the league. It's long gone. Now we have data that helps to determine with great accuracy where exactly snipers attack from better. And on the basis of such data, you need to determine the distance by which you need to move the three-point line. We need to figure out where the league is going to hit exactly one-third of all 3-point attempts.

The graph helps you understand two key ideas:

1. There is a correlation between distance and hit percentage, but it's not as strong as you might think.

2. Across the league, the closest 3-pointers—those from the corner—are shot within 40%. Given that two-pointers from three meters away are shot with 40 percent accuracy, why would anyone shoot a two-pointer at all?

But the graph does not answer the key question: where should the line be for three-point attempts to hit 33.33%? It's a tough question, but after looking at almost 70,000 3-pointers from the 2017/18 season (which excludes home-field shots), some estimates can be made. NBA sharpshooters made 33.33% of their long shots from 7.8 meters, exactly two feet from the 3-point arc.

NBA sharpshooters made 33.33% of their long shots from 7.8 meters, exactly two feet from the 3-point arc.

So why not move the arc based on this analysis?

The cool thing is that we can update this data every year. The qualifications of snipers change, and the arc can also move in accordance with it. Each summer, we will study the data from the past season and move it accordingly, focusing on specific data. Three-pointers will always be worth one point per possession. Everyone's long shot percentage will suffer, but the best shooters in the league will still be valuable, in fact, they will be much more valuable.

And fear not: Steph Curry will continue to be among the MVPs. In 2017/18, 36 people made at least 100 three-point shots from 7.8 meters from the rim, but only one made more than 40% - Curry had 43.6% of 172 three-point shots made outside the hypothetical arc.

In contrast, those who are not very good will become less valuable with the new line, and their ability to "stretch the court" will suffer. For example, Andrew Wiggins only made 22.8% of his 123 3-pointers in the 2017/18 season. Defenders will not pay attention to him at this distance.

For example, Andrew Wiggins only made 22.8% of his 123 3-pointers in the 2017/18 season. Defenders will not pay attention to him at this distance.

Many of the most active shooters in today's league are already minimally effective, and if the line is moved back, then they will completely go into the red. The number of players focusing on three-pointers will decrease, and the league will need to be more careful about the two-point zone and those who can benefit from there. Channing Fry would have to work hard. Some 3-pointers would lose playing time, deviated shots would be back in vogue, and there would be more variation in different types of shots. Many three-pointers would turn into "bad shots." And all this would have happened thanks to analytics - Mori would have been bitten by his own snake.

Get three-pointers out of the corner

Ray Allen's incredible shot in Game 6 of the 2013 Finals is arguably one of the best shots in league history. Enough has been said about that shot and how Ray carefully moved to his favorite spot, received a pass from Chris Bosh there, and with a merciless move equalized the score. But here's what's interesting. The place where Ray made the throw - that tiny corner near the front - is usually considered "the smartest shot in the game." In fact, this is the most stupid throw in the game.

But here's what's interesting. The place where Ray made the throw - that tiny corner near the front - is usually considered "the smartest shot in the game." In fact, this is the most stupid throw in the game.

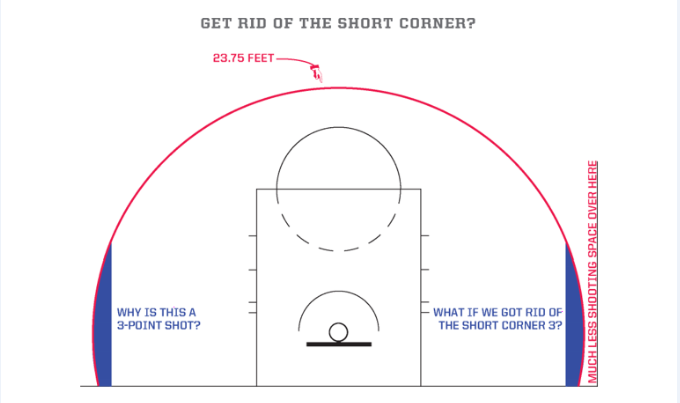

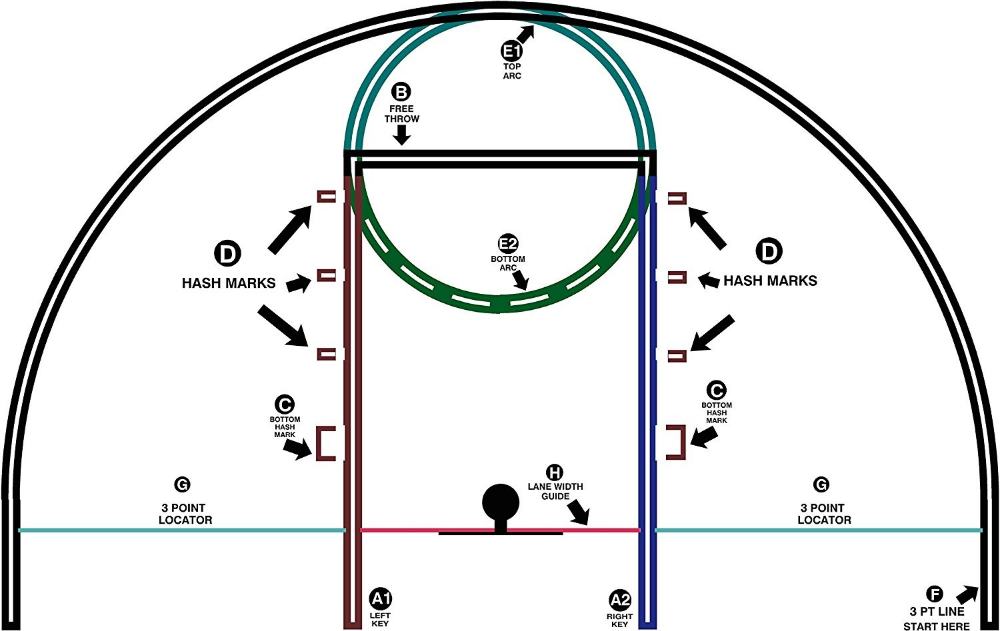

Analytically, a three-pointer from the corner should not exist. It stems from a mistake, from a seemingly insignificant provision passed in 1961 that has affected every possession in the NBA ever since. Why on earth does a three-point arc include two straightened fragments?

The three-point line is 23.75 feet everywhere, and only at the corners does the arc straighten out and remain 22 feet from the hoop. Based on this markup, some 23-foot throws are worth two points, while others are worth three points. From all angles, throws from 22.1 feet are worth two points, but near the front, for some unknown reason, they are worth three. You don't have to be Billy Bean to know this doesn't make any sense.

Platform width - 50 feet. The place in the corners is modeled to leave three feet of space for snipers. After all, the guys in the NBA are giants with huge feet and it takes time for them to catch the ball and make the shot. If the arc were 23.75 feet at all levels, then throwers would have 15 inches left, which is clearly not enough for Matt Bonner's sneakers.

After all, the guys in the NBA are giants with huge feet and it takes time for them to catch the ball and make the shot. If the arc were 23.75 feet at all levels, then throwers would have 15 inches left, which is clearly not enough for Matt Bonner's sneakers.

Although 3-pointers from the corner make up only 10 percent of shots, they affect nearly every possession. It's as if the minimal solution of cutting the arc in the corners has completely changed the aesthetics of the NBA. Not only do teams and players constantly use this space for shots, but they also use the space to stretch the defense. Stretch guard now implies that the player is stomping away from the ring in one place. It does nothing, but this function is incredibly valuable. For the most part, 20-40 percent of offensive players in the NBA do nothing but chill in the corners. And at the same time, they have a huge impact on the game - they attract defenders to themselves and do not give those opportunities for safety net.

Not for the first time in history, almost immobile players affect the aesthetics of the game.

Prior to the adoption of the Mikan rule, players pushed close to the ring, where defenders and attacking players fought for space and were not going anywhere. Rule changes like three seconds and illegal defenses were deliberately designed to force basketball players to move and leave their favorite spots. Today, in the era of three-point basketball, the favored points have moved to the arc. But for some reason no one cares. The league has been ruthless about standing inside, but completely oblivious to standing in corners.

This is another example of how tough the league has been on the "big" ones and how flippant their little counterparts are.

Stand-up corner shooters essentially turn many NBA possessions into a three-on-three game. Players in the corners and their guardians turn into extras - unless, of course, one of the defenders tries to go to safety net against the passing one. In this case, a three-pointer from the corner arrives after the pass and the discount.

In this case, a three-pointer from the corner arrives after the pass and the discount.

But is it interesting? Does anyone even come to an NBA game to watch people stand in the corners of the court?

One easy way to bring more movement to basketball and breathe life into a two-point game is to have smaller boys hanging out at the front. Moving the arc back 23.75 feet won't completely eliminate three-pointers from corners, but it will at least close a gap in basketball rules. Between 2013/14 and 2015/16, the NBA shot 44,000 three-pointers from the corner, or 7.3% of all shots. In general, they were implemented with 39 percent accuracy and brought 1.16 points per throw, this is a very high efficiency for a throw .

At the same time, 36.79% of all attempts were made from areas in the corners where the arc did not straighten - at a distance of 23.75 feet from the ring. This is fully consistent with the throwing efficiency from other areas behind the arc.

At the same time, most of the three-pointers from the corner fell on short sections - 91.4 of all three-pointers from the corner.

So what happens if you remove the loophole?

1. It will be more difficult for snipers, and this will encourage them to move more and not stand in the corner. A distance of 23.75 feet across the entire arc would fit within the modern court, but leave little room for a throw. Since these guys have huge feet, they will be uncomfortable shooting from this area - and they will go to where it will be easier for them to find the necessary balance, time and opportunity to shoot.

2. There will be fewer three-pointers from the corner. Worst of all will be constant questions: was there a spade or not? This will lead to even more tedious repetitions that no one will like. As a result, the court can be expanded - from 50 to 54 feet - but this will be a headache for each arena, since it will require changing the placement of the front rows.

3. Three-pointers from the corner will be less effective.

Enter Special Lines

Warning: this is one of the dumbest ideas I've ever come up with. But some have told me she's great.

What if each team placed the three-point line wherever they wanted?

Since the birth of basketball, the courts in all places have been the same size. This regularity is what distinguishes basketball from baseball and football, which have different markings in different arenas.

Now imagine what would happen if different NBA teams could place the three-point arc differently? And focus on the strengths and weaknesses of your composition?

One could imagine Golden State moving the arc closer to hit more 3s. At the same time, all their snipers feel great far from the ring: Curry, Durant and Thompson easily hit from 7 meters. If they moved the line there, they would thus force the opponent to play in uncomfortable conditions for themselves.

Other teams could change the configuration of the arc and thereby confuse the opponent.

What if some team wants to remove three-pointers from their floor?

This would suit a team with a dominant center like Hassan Whiteside, a team like Miami. Without a three-pointer, the opponent would have to replay the Heat under the basket.

Allow 3-point hitting

This may sound crazy – maybe it is – but basketball was originally allowed to hit balls on shots. Because George Mikan did it too well and became the best defenseman, the league changed the rules and landed the hardest hit on the centers. But the madness is also the addition of a three-pointer. If we allow the ball to be dropped on long shots, we will help the centers and breathe life into two-point attacks.

It will be the same as Kevin Garnett did when he hit the balls after the whistle, but only during the game. Every time someone throws a long throw, under the basket, the guys will fight not only for the rebounding position, but also for the blocking position. It will become much harder to make open three-pointers. Sharpshooters like Korver or Ariza will have to not only shoot at the basket, but also take into account whether their shots can be blocked by a post under the basket.

Sharpshooters like Korver or Ariza will have to not only shoot at the basket, but also take into account whether their shots can be blocked by a post under the basket.

One can imagine Jeff Van Gundy exclaiming, “What was Ariza thinking? He threw the ball when Rudy Gobert took a position near the ring!

Centers will gain value again, and the small five will lose its meaning, as sharpshooters will no longer be able to be as effective. Basketball will become more athletic, there will be more struggle at the ring.

The ability to swipe long shots will add to the tension: everyone will not only watch the 3-point parabola, but also at the same time what the “big” players are doing near the basket.

Also, this will restore the value of medium rolls, where players can roll and not worry about some monster swiping them at the last moment. So long two-pointers will no longer be the worst attempts on the court, the importance of post players, those who can make attempts with deviation will return . .. should we revise the rules that were designed to limit the game of Mikan and Chamberlain? After all, teams no longer load the ball under the hoop.

.. should we revise the rules that were designed to limit the game of Mikan and Chamberlain? After all, teams no longer load the ball under the hoop.

What if we convert the three-second zone back into a "key" and return it to its original shape?

Many fans are more open to rule changes when it comes to returning to the roots of the game. If we make the "paint" narrower, then this can give impetus to more involvement of the "big ones" in the freed space.

First of all, this will obviously give the big attackers more options within a few feet of the hoop, making it easier for them to score.

Secondly, the teams will need to pay more attention to the protection under the basket.

The three second is now 16 feet wide. What if you reduce it to 6 or 12 feet? Recall that it was increased due to the fact that Wilt destroyed everyone under the shield. But now there are no Wilts left. We have legally abolished them.

Now it's easy to find Stephs and Clays, Hardens and Westbrooks, but no Wilts, Shaks, Mikans or Karims. Hell, even the McHales are gone. Instead, people like Draymond Green become dominant defenders.

Hell, even the McHales are gone. Instead, people like Draymond Green become dominant defenders.

Revise contact rules

Another reason why Draymond is so effective at defending against the big ones is because of the strange contact fixing rules. The "big" ones who attack inside are out of the game because their craft is "inefficient" compared to the craft of those who throw from afar. Two-point attempts don't come in often enough. But why?

Anyone will tell you that the closer to the ring, the easier it is to hit it. But in the NBA, the relationship between efficiency and distance is not so simple. First, because of the 3-point arc, where attempts from 7 meters are worth a point more than attempts from 4 meters. Secondly, because of the defenders, which affect the offensive qualities of the player making the throw.

Although this is obvious, there is also a third. Defenders can defend harder. Anyone who has seen Shaq or Duncan in the final matches knows that they were shoved, clung to jerseys, elbowed.

The Golden State in many ways became a juggernaut that was light years ahead of everyone, largely due to the fact that Draymond Green was literally allowed to "hold his opponent", in the sense of holding him with his hands, grabbing for the shirt, push it away. Green is allowed to defend against Adams, Davis, Dwight Howard in a way that classic centers are not allowed to play against Green himself. Not to mention his little partners.

The rules of the NBA are such that defensemen under the rim are allowed much more. You can cling and shove Shaq, but the judge does not see anything. But if you touch Steph with your finger, it will cost the opponent three free throws - and this, by the way, is the most significant punishment in the game. Every time Steph or Harden can get on the line for three shots, it gives more than two points per possession. Shaq could have put through Draymond and crushed the shield. But it's all early only two points.

What if the league were more consistent in officiating across the court? At the moment, it turns out that the difference in the definition of contact in different places on the court is another impulse for the steady growth of three-pointers.

***

The introduction of the 3-point line is not just the biggest change in basketball history, it's just the most successful change in the rules, including allowing inside contact, the 3-second rule, and expanding the 3-second line - all of which saw the Bigs lose the advantage . They were all effective. But the three-pointer continues to be more effective with each new season. We're moving towards a league where everyone should be able to hit a three-pointer, we're also moving towards a league where there won't be any big guys who can't.

But this is not required.

And here's an idea for you.

What if we used the same analytical methods that created modern basketball to optimize the rules and court markings?

Basketball is the best sport for many reasons. One is that basketball exhibits regular flashes of athletic excellence that can take many forms. Ask anyone who has seen the Magic, Jordan, LeBron or Durant play. Surely, at least once they surprised you. It is even more likely that such amazing episodes did not include a three-pointer after receiving. Let's be honest: 3-pointers are not the best part of basketball. Compared to blind passes, 7-footer dunks, or balls from unthinkable deflected shots, three-pointers are boring.

It is even more likely that such amazing episodes did not include a three-pointer after receiving. Let's be honest: 3-pointers are not the best part of basketball. Compared to blind passes, 7-footer dunks, or balls from unthinkable deflected shots, three-pointers are boring.

Basketball is especially good when diverse players - players of different sizes and different specializations - complement each other and delight us with the coherence of the action. But the era of three-pointers threatens with monotony. The best league in the world is moving towards one variation of attack and one type of scoring becoming prevalent. There is no doubt that 3-pointers can be very emotional. But at what point will there be too many of them?

The Rockets in 2017/18 became the first team in history to make more than half of their shots from behind the arc. Many people think that this is not very good. It might be a genius strategy, but I'd rather watch Barkley's fat ass shoving under a shield than Eric Gordon standing on the arc for a long time and then launching a long-range attempt from there. The latter is exactly what both the current markup and the current rules contribute to. More Andersons, less Barkleys. The Rockets don't kill basketball, it's just the smartest and most obvious example of a team taking advantage of the rules.

The latter is exactly what both the current markup and the current rules contribute to. More Andersons, less Barkleys. The Rockets don't kill basketball, it's just the smartest and most obvious example of a team taking advantage of the rules.

You can no longer be Charles Barkley. You can't be McHale anymore. Or Malone. You can't be Karim.

If Jordan had been drafted in 2019, he would have mostly looked for opportunities to shoot from the perimeter, rather than bet over weirdos of all sizes. Everyone who was lucky enough to grow up in the Jordan era still considers him to be the best player of all time. He wasn't just my favorite basketball player, he was my favorite TV show. His performances were not to be missed. He was the most popular star in America. But the two major shots of his career—the one that won the Jazz and the one that won the Georgetown—are exactly the kind of middle-range attempts that are considered idiotic in modern basketball. In fact, Jordan's entire arsenal of side and side throws that Jordan so adored would now be called "bad shots. " For a generation of boys, Jordan's aesthetic defined the greatness of basketball and instilled in them a love for the sport. "His Air" took the league to another level as he soared towards the ring. And we all wanted to "be like Mike."

" For a generation of boys, Jordan's aesthetic defined the greatness of basketball and instilled in them a love for the sport. "His Air" took the league to another level as he soared towards the ring. And we all wanted to "be like Mike."