Home »

Misc »

How far is 30 feet on a basketball court

How far is 30 feet on a basketball court

Basketball Court Dimensions, Gym Size, Hoop Height

Basketball court dimensions and size vary based on the level of play. To help explain the various sizes, we’ve created a chart and diagrams that should help you. And we’ve organized the material into a helpful Q & A format.

What is a basketball court size?

Well, it depends on each court you measure — but there are some standards. The age of the players who will be the primary users and budgets are considerations for court builders.

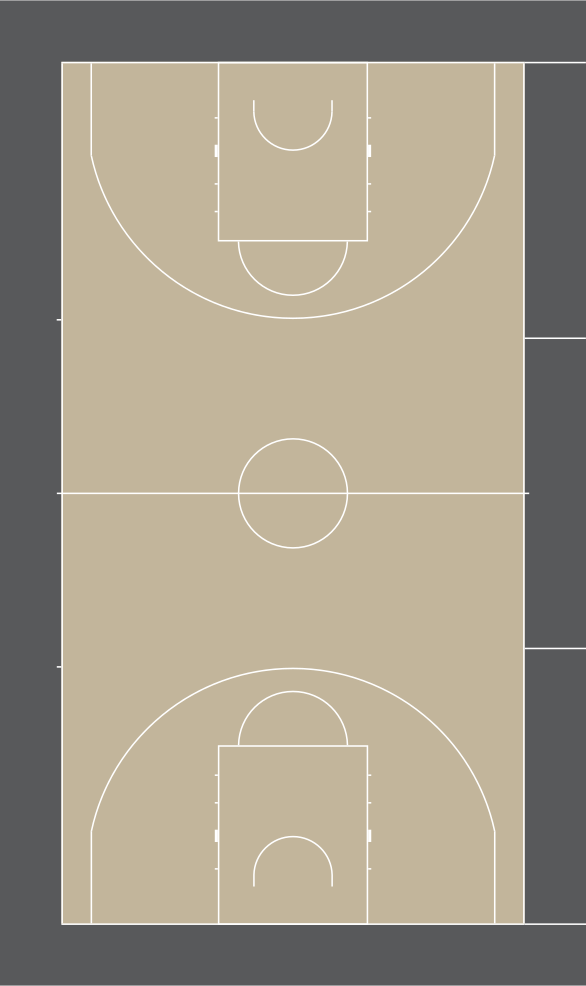

Basketball Court Dimensions

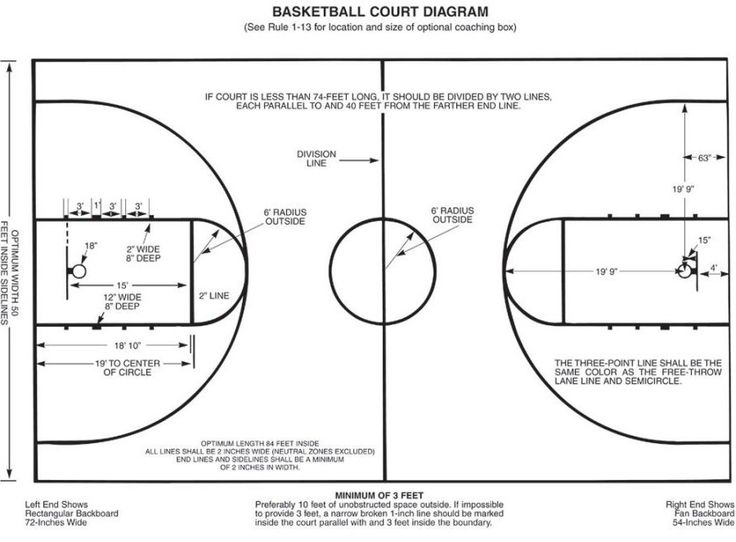

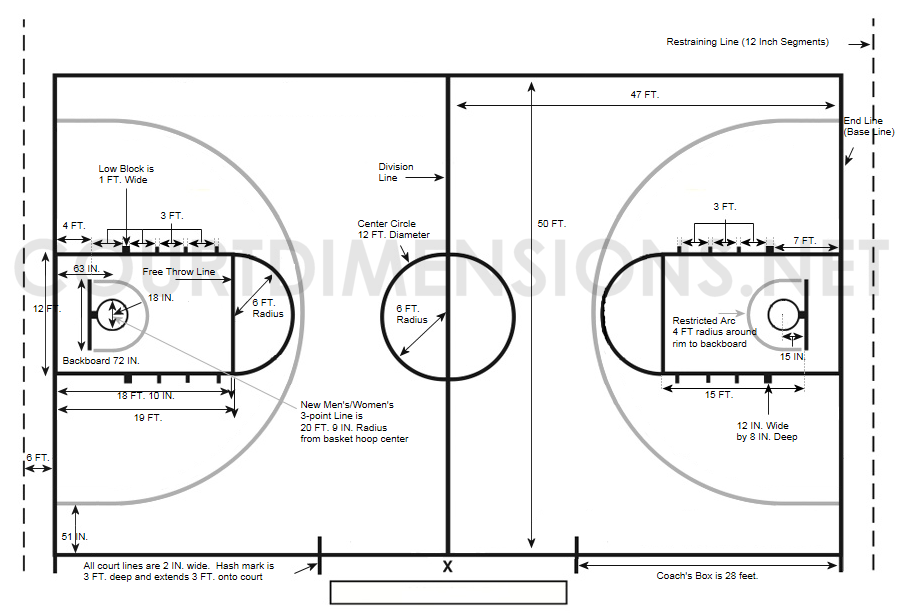

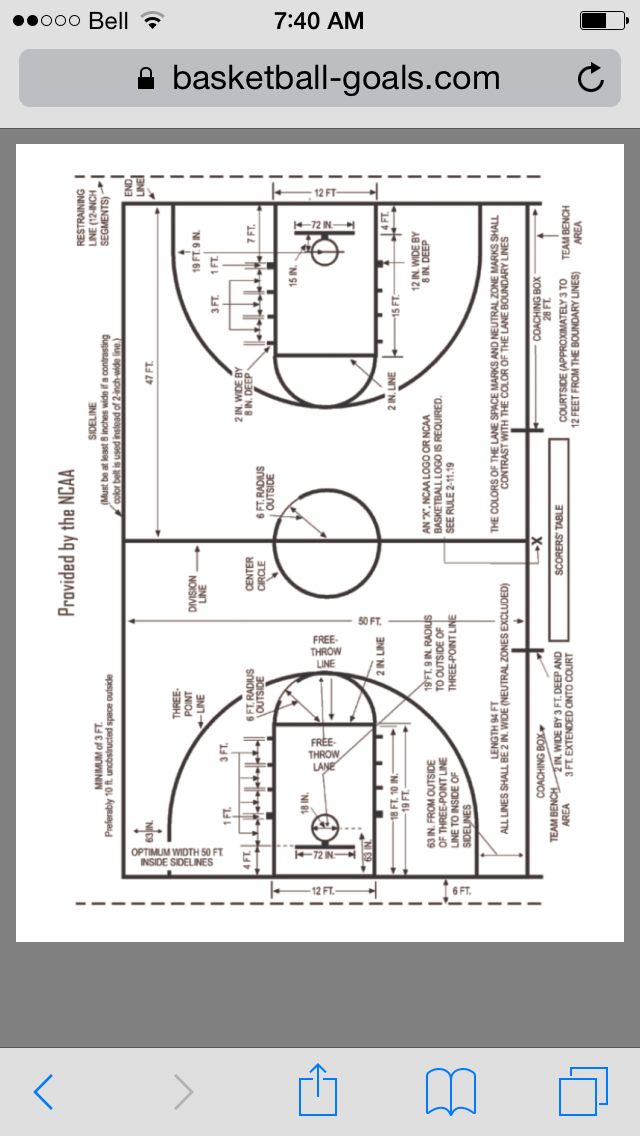

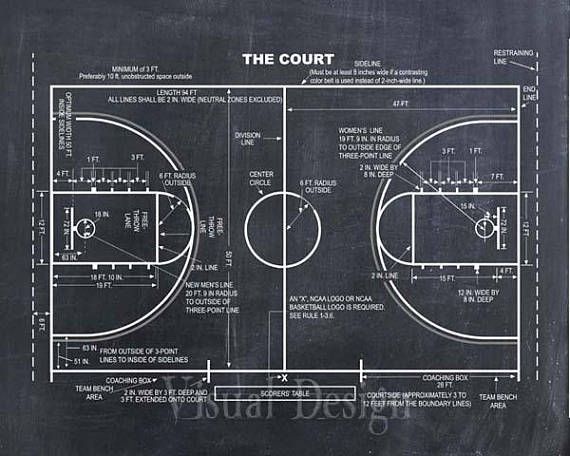

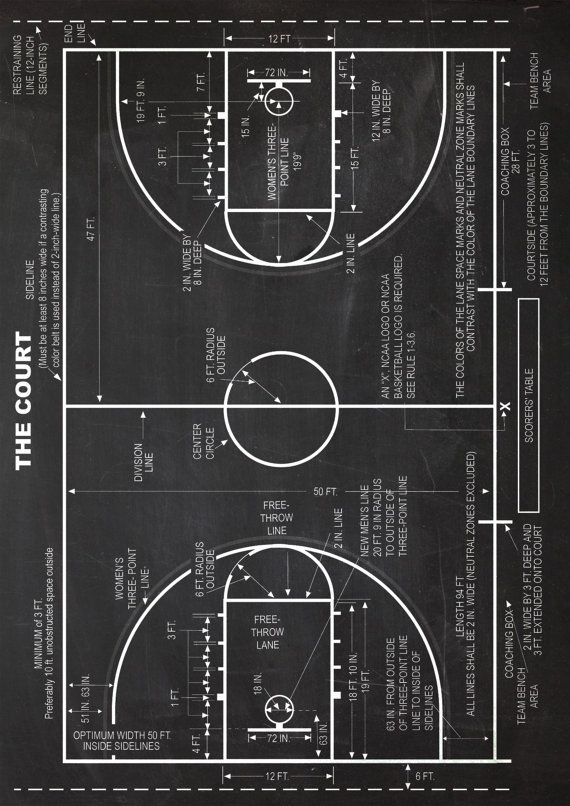

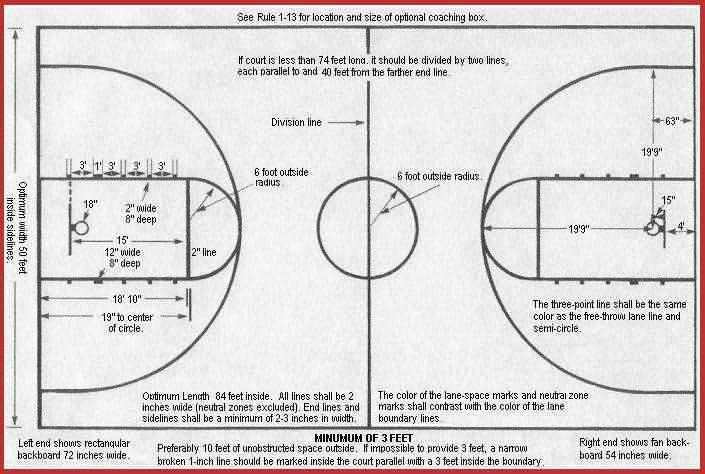

Regulation basketball court dimensions are 94 feet long by 50 feet wide.

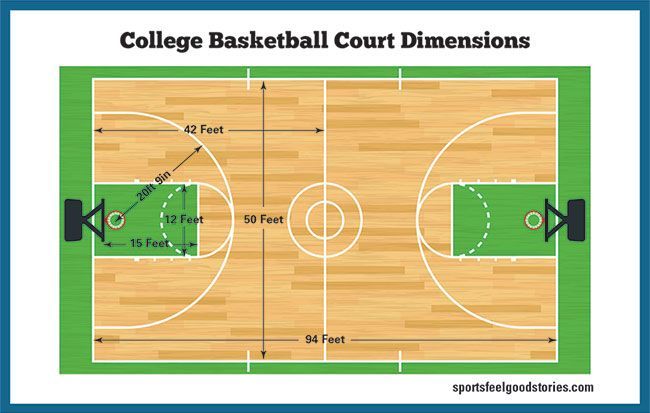

Basketball court size varies depending on the league and level of play. The court measures 94 feet long by 50 feet wide for NBA court dimensions and WNBA and college. Note the paint area – the free throw lane – is 16 feet across. The foul line is 15 feet from the face of the backboard and 2 inches wide.

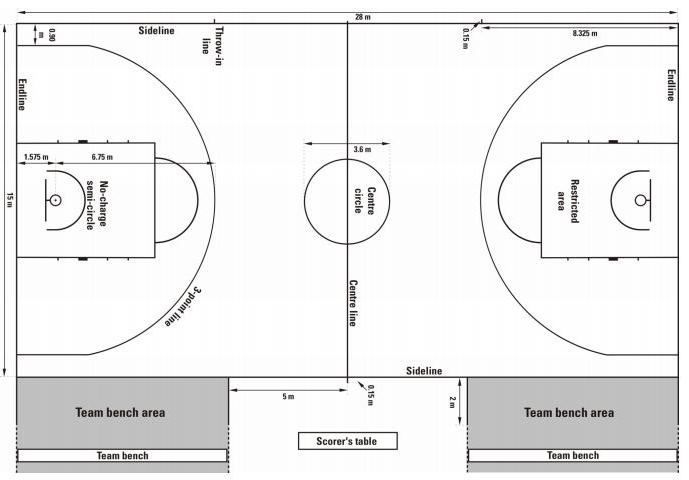

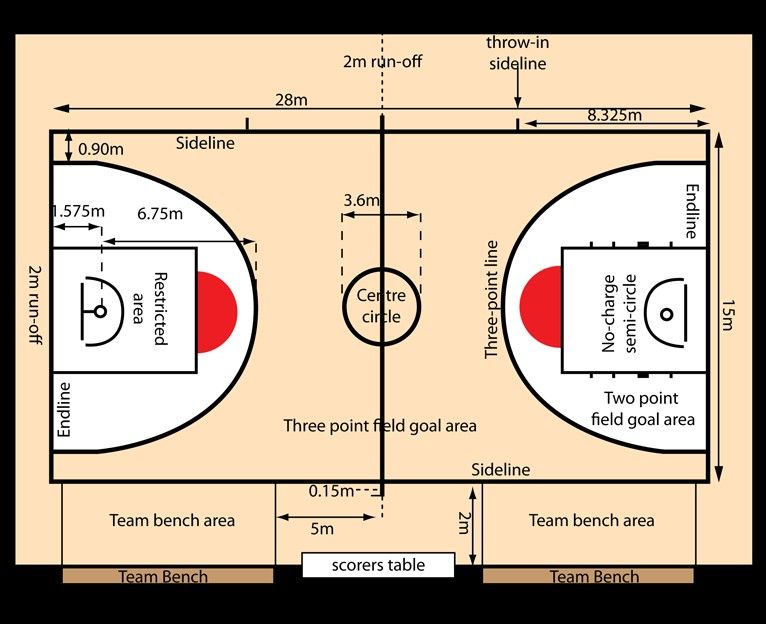

International Basketball Federation (FIBA) and Olympic basketball courts call for the court to be slightly smaller at 91.![]() 9 feet by 49.2 feet. In meters, that’s 28 by 15 meters.

9 feet by 49.2 feet. In meters, that’s 28 by 15 meters.

NBA Court Dimensions Diagram

High school basketball court dimensions

The high school and junior high basketball gym courts measure 84 feet long by 50 feet wide. Court markings reflect those dimensions.

You might like Kawhi Leonard Profile.

High School Basketball Court Diagram

At a younger level of play than college or pro, the court length is 10 feet shorter at 84 feet.

Read all about Larry Bird: Boston Celtic, Star Shooter (and Trash Talker)

How long is a basketball court?

So, what are court dimensions in feet? The high school court is 84 feet long. The length of an NBA court is exactly 10 feet longer. College and professional league games, including the WNBA, are played on a 94-foot-long court.

One of the most famous college facilities is Pauley Pavilion, where the UCLA Bruins play.

Visit: Stephen A. Smith Profile.

College Basketball Court Diagram

What are court dimensions in meters?

The metric size of a professional court is 28. 65 meters long by 15.24 meters wide. The high school court measures 25.6 meters long.

65 meters long by 15.24 meters wide. The high school court measures 25.6 meters long.

What are half-court dimensions?

Half-court dimensions are 47 feet long for the pros and 42 feet long for high school.

See Basketball Roles and Responsibilities of Each Position.

What are the half-court dimensions for a backyard?

Youth half-court dimensions are usually 42 feet long by 37 feet wide. High school half courts are slightly larger, 50 feet long by 42 feet wide.

Check out Ben Simmons Profile.

What are backyard court dimensions?

Backyard courts can be whatever size you wish (or can fit), but typically they are 90 feet long by 50 feet wide.

What are youth court dimensions – Middle School and High school?

The middle school court size is 74 feet long by 42 feet wide. High school courts are slightly larger, at 84 feet long by 50 feet wide.

Looking for a basketball court in your area to play? Check out The Original Basketball Court Finder.

Basketball Hoop Height and Size

It’s critical that you set the goal at the proper height. Here are your guidelines.

See How many teams make the NBA playoffs?

What is the regulation basketball rim height? How tall is a hoop?

The distance from the gym floor to the rim is 10 feet. This rim height is the same for Junior High, High School, NCAA, WNBA, FIBA, and the NBA. Some kids’ leagues will lower the hoop to 8 feet or 9 feet to acknowledge that younger kids have difficulty shooting at ten feet-high hoops.

You might like Jumbotron Dancer Entertains Celtics’ Crowd.

How wide is an NBA basketball hoop? What is the NBA rim size?

The rim size is the same for all game levels – junior high, high school, NCAA, WNBA, NBA, and FIBA – at 18 inches in diameter.

Basketball Free Throw and 3-Point Distance

Read the guidelines below carefully, as the three-point distance varies by player.

What is the free-throw line distance? How far is the free-throw line?

The free-throw line is measured from the shooting line that intersects the key to the floor directly underneath the backboard. The free throw distance in the NBA, WNBA, and NCAA is 15 feet.

The free throw distance in the NBA, WNBA, and NCAA is 15 feet.

Did you know that Steve Nash was the best percentage shooter of free throws in the NBA? He shot 90.43% from the line making 3,060 of 3,384 attempts.

What is the high school 3-point line distance?

The 3-point line for high school is 19.9 feet from the basket.

What is the college 3-point line distance?

The 3-point line for both NCAA men and women is set at 20 feet, 9 inches from the hoop.

What is the WNBA 3-point line distance?

The WNBA 3-point line is 22.15 feet from the basket. From the corners, the distance is 21.65 feet.

What is the NBA 3-point line distance?

The pros shoot 3-pointers from beyond the arc, 23.75 feet from the basket. From the corners, the distance is 22 feet.

Check out Basketball Slang

Size of the Basketball

Matching the size of the basketball to players’ hand size makes a difference. Read on.

Read on.

What is the ball diameter and circumference?

The size of the ball is different for men’s, women’s, and youth leagues.

For the NBA, men’s college, and boys ages 15 and up, players play with a 9.43-9.51 inch diameter (the width measured left to right) basketball. The ball’s circumference (the distance measured around the outside) is 29.5 inches. The official NBA game ball is made by Spalding and measures 9.43-9.51 inches in diameter, or 29.5 inches (75cm) in circumference.

NCAA women and the WNBA use a slightly smaller ball with a roughly 9.07-9.23 inch diameter and 28.5-inch circumference.

The ball used in boys’ youth leagues has a 28.5-inch circumference. Girls’ youth basketballs are 27.5 inches in circumference. Kids 5 to 8 years old use the smallest ball at 25.5 inches in circumference.

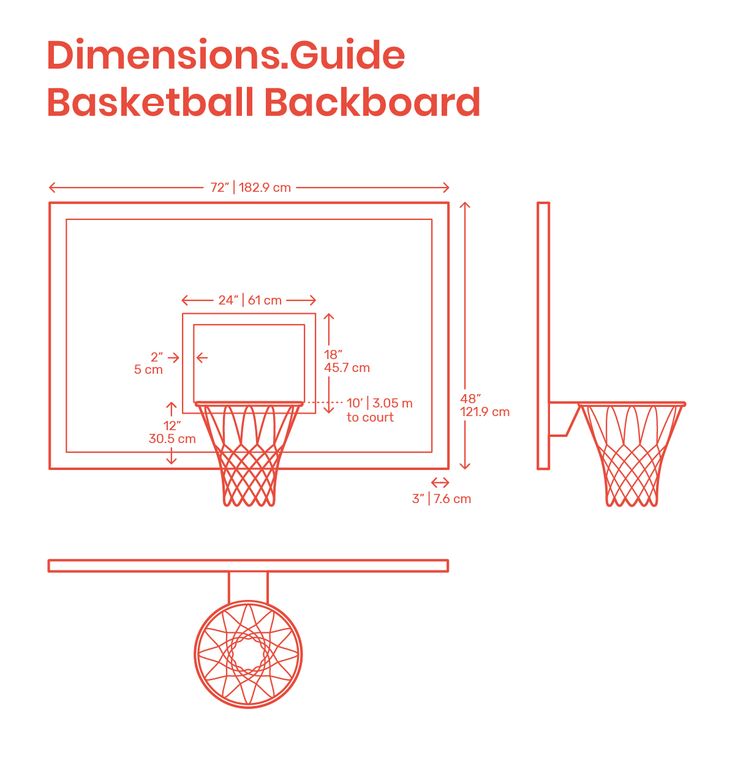

Backboard, Baseline, and Key

The backboard is four feet out from the baseline, marking the end of the players’ active playing surface.

The key is 16 feet wide and 19 feet from the foul line to the baseline.

Inside the key, a four-foot arc is designated to align with the center of the basket to mark the restricted arc. If a defender is within this arc, they cannot draw a charging foul.

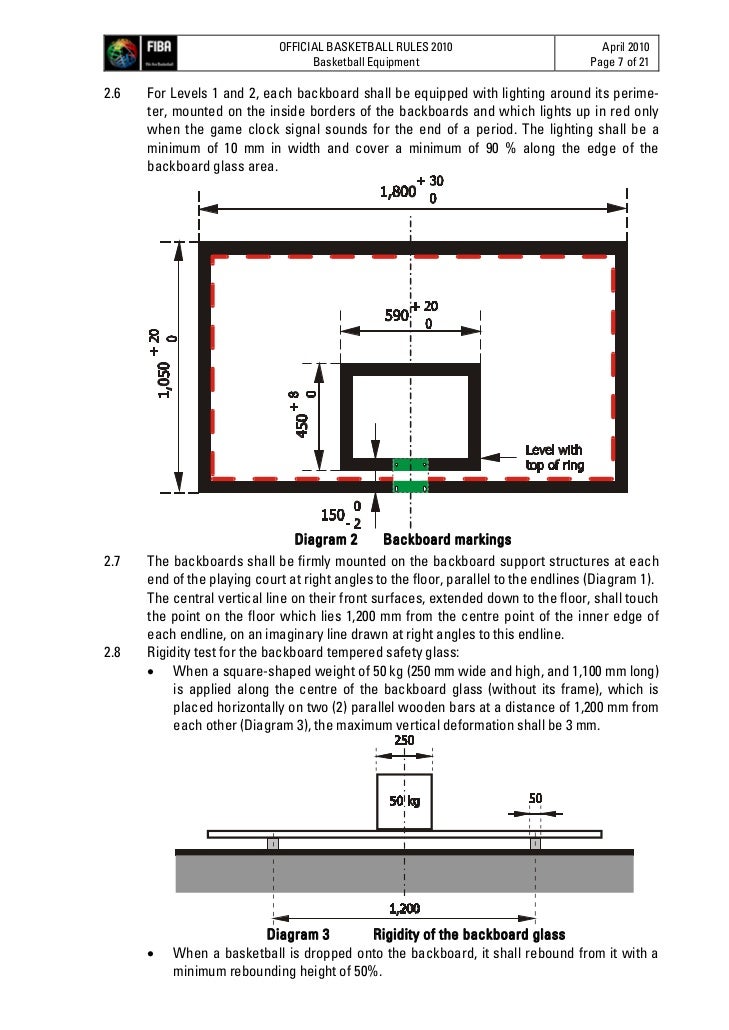

Regulation backboards are six feet wide and 42 inches tall.

Free throw markings

Short lines are drawn three feet apart along both sides of the key area to designate the standing positions for rebounders when a free throw is being shot. The first line is drawn seven feet from the baseline.

A six-foot arc (half circle) starting from the free-throw line away from the basket completes the key area.

Core components of basketball courts

Baskets, free-throw lines, three-point arcs, and the half-court line are some of basketball courts’ foundational elements. Court lines mark 94 feet in length by 50 feet in width for NBA courts. The half-court line is at 47 feet. Indoor courts are frequently made of hardwood-like polished maple. Outdoor courts may be composed of asphalt, concrete, or other pavements.

The words baseline and end line both refer to the ends of the court running behind the goals.

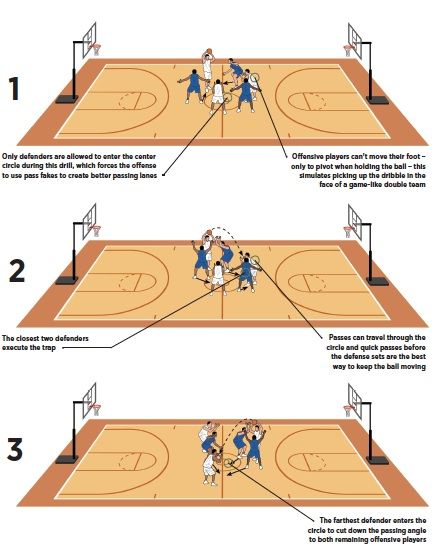

In the middle of the half-court line is a tip-off circle that has a six-foot radius. This is where the opening jump ball takes place.

The backcourt refers to the half of the court where the team’s basket is defended. The boundary lines include their end line, sidelines, and the half-court line of the playing court.

For international play, the standard court size is 28m long and 15m wide, measured from the inner edge of the boundary line.

The 3-Point line

The NBA 3-point arc is 22 feet to the center of the rim. Women’s and Men’s college basketball court features a 3-point arc of 20 feet 9 inches. High school basketball courts have a 3-point arc that is 19 feet 9 inches away from the center of the rim.

Great Basketball Courts Everyone Should See

Rucker Park in Harlem, New York. Where street legends go to make their name. Home of Kareem Abdul Jabaar, Nate Archibald, and Connie Hawkins. Even Kevin Durant and Kobe Bryant have made appearances.

Even Kevin Durant and Kobe Bryant have made appearances.

United Center, Chicago, Illinois. Michael Jordan won 6 NBA titles while calling this his home court.

Hoosiers Gym in Knightstown, Indiana. Gene Hackman + Dennis Hopper + Picket Fence = the best basketball movie ever.

Pauley Pavilion in Los Angeles, California. Home to the UCLA Bruins and John Wooden’s greatest college hoops dynasty.

Madison Square Garden, Manhattan, New York. Home of the Knicks with a household name that needs no introductions.

The Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. One word: “Showtime!”

The Swim Gym, Beverly Hills High School in Los Angeles. Remember “It’s a Wonderful Life” and the retractable gym floor? This is the place. Built in 1939, a 25-yard pool was placed under the gym floor. It’s a Wonderful Life was a 1946 movie.

Timing of a Game

Here are the total game times for basketball games for each level of play. Remember that time-outs, TV breaks, half time, and other play stoppages will draw out the real-time of a game 2 to 3 times longer than the timed play.

How long is a high school game?

High school basketball games consist of four 8-minute quarters for 32 minutes of game time.

Length of college basketball game?

In the NCAA, college games consist of two 20-minute halves for 40 minutes of game time.

How long is a WNBA basketball game?

WNBA basketball games consist of four 10-minute quarters for 40 minutes of game time.

Length of an NBA basketball game?

NBA games consist of four 12-minute quarters for 48 minutes of game time.

How long is the shot clock?

The shot clock requires offenses to shoot before a timed period runs out. If a shot is not made during that period, a shot clock violation is called, and the ball is turned over to the opposing team.

In high school games, the shot clock varies. For men’s college hoops, the shot clock is 35 seconds, and for women’s college is 30 seconds.

The WNBA shot clock is 30 seconds, while the NBA limits the shot clock to only 24 seconds.

Basketball Court Fun Facts

Do you know everything about hoops courts? Try answering these trivia questions.

1.) What type of wood is used for NBA courts?

Maple is selected for its hardness and light color. The lightness helps provide contrast to the ball to follow the action in person and on TV. The lighter color reflects light better, too.

2.) How often does the NBA require teams to replace the floors in arenas?

Every ten years. But, sometimes, a team receives a waiver if the floor is still in great shape.

3.) What three NBA teams were ranked the highest in appearance by the Chicago Tribune?

Charlotte Hornets, Brooklyn Nets, and the Boston Celtics floors were ranked the highest by a panel selected by the newspaper.

By Greg Johnson & Mike O’Halloran

Greg is a designer and writer based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Mike has authored three books on basketball coaching and has coached ten different teams.

You’re on our Basketball Court Dimensions page.

Further Reading

Hoops Quotes

Slogans

NBA Players By The Numbers: Wingspans, Verticals, Hand Sizes

Fun Basketball Games For Kids to Improve Shooting

Everything You Need to Know About Basketball Court Dimensions

Of the two major American-invented sports — baseball and basketball — only one has gained worldwide popularity. We play baseball across parts of the globe, but we play basketball worldwide. You can play with as few as two people and as many as ten. Shoot hoops indoors and outdoors and on any surface hard or flat enough to bounce a ball.

Indoor courts are usually made from hardwood, though other, more easily-maintained surfaces are gaining in popularity. Outdoor courts can be either asphalt or concrete. You can put a permanent basketball court just about anywhere you would like. Don’t have the room for a full-length court? Fitting just a half court into your driveway, backyard, or commercial gym would be just as useful.

So, have a space in mind and wondering “What are the dimensions of a basketball court?” Let’s take a look at the standard sizes for every level of basketball, from high school all the way up through international competition.

NBA Basketball Court DimensionsThe National Basketball Association, better known as the NBA, boasts the largest court dimensions of any level of basketball — domestic or international. The outer dimensions are 94 feet long by 50 feet wide. The half court line is, as the name would suggest, halfway between each end line. In the middle of the half court line is a tip-off circle with a six-foot radius, which often sports the home team’s logo.

The key is 16 feet wide and 19 feet from the baseline to the foul line. A semicircle with a six-foot radius extends from the foul line. Some courts have the other side of the half-circle drawn in a dotted line inside the key to complete the circle and create a clear boundary for any jump balls.

The backboard protrudes four feet out from the baseline, and the rim of the basket hangs 10 feet off the ground. Subtracting the four feet overhang from the 19-foot length of the key, we get the familiar 15-foot distance from the foul line to the front of the backboard. It’s a misconception that the foul line is 15 feet from the center of the basket. The backboard itself measures six feet wide and 42 inches high.

Inside the key, a four-foot arc is aligned with the center of the basket to designate the restricted arc. If a defender is inside this semicircle, he cannot draw a charging foul. Along both sides of the key, lines are drawn three feet apart to create the standing positions for other players during a free throw attempt, starting with a box that is seven feet from the baseline and one foot wide.

Outside the key, the three-point line forms an imperfect arc stretching one side of the baseline to the other. The arc isn’t a perfect circle because it would run out of bounds on the sides of the court.

Instead, the three-point line runs in a straight line from the baseline out 16 feet, nine inches, at which point the line begins to curve. The straight lines are an even 22 feet from the center of the basket, and on the arc, the distance is 23 feet and nine inches.

Starting at the baseline and running 28 feet toward the center of the court, a line bounds the team bench area. The line also acts as the starting place for inbounds passes after timeouts and fouls.

WNBA Basketball Court DimensionsThe Women’s National Basketball Association or WNBA’s court dimensions are identical to the NBA court in every way except the three-point line. Instead, the distance is equal to the International Basketball Federation (FIBA) at 22.15 feet from the center of the hoop. WNBA teams share arenas and playing surfaces with the NBA, which is why it’s no wonder the court dimensions are so similar.

NCAA Basketball Court DimensionsNational Collegiate Athletic Association or NCAA basketball courts have similar dimensions to the NBA and WNBA, which include the:

- Court

- Foul line

- Backboard

- Basket height

- Tip-off circle

That said, there are a few significant differences in the dimensions of the NCAA court. For starters, the key is only 12 feet wide, rather than 16. The first box on the side of the key is only six feet from the baseline, not seven. The restricted area under the basket is also one foot smaller, at three feet in diameter rather than the NBA’s four.

For starters, the key is only 12 feet wide, rather than 16. The first box on the side of the key is only six feet from the baseline, not seven. The restricted area under the basket is also one foot smaller, at three feet in diameter rather than the NBA’s four.

However, the most recognizable difference between the NBA’s court dimensions and the NCAA’s is the distance of the three-point line. The NCAA three-point line is only 20 feet, nine inches from the center of the basket. Because of the smaller diameter, it is a continuous arc from one side of the baseline to the other, with no straight lines necessary to create space on the sidelines.

The difference in three-point line distances is the biggest adjustment for shooters to make as they begin their professional careers, and also why it’s so difficult to project how well a player will shoot in the pros.

High School Basketball Court DimensionsHigh school basketball courts are a little different from their college and professional counterparts. The most noticeable difference is that the court is a full 10 feet shorter, measuring only 84 feet. However, there are some similarities. The court is still 50 feet wide. The basket is also 10 feet off the ground.

The most noticeable difference is that the court is a full 10 feet shorter, measuring only 84 feet. However, there are some similarities. The court is still 50 feet wide. The basket is also 10 feet off the ground.

The tip-off circle has a six-foot radius, just like the big kid courts, and while the high school landscape isn’t as standardized as college and professional basketball, the backboard is supposed to have the same measurements as the NCAA and NBA.

Just as in college and professional basketball, the foul line is 15 feet from the backboard, and the key is 19 feet long. It’s also the same 12 feet wide as the NCAA — four feet narrower than the NBA and WNBA.

The other visible difference is the distance from the three-point line. Shorter than either the NCAA or NBA, the high school free throw line is just 19 feet, nine inches from the center of the basket. Additionally, high school basketball courts do not have any restricted area under the basket, since that rule doesn’t exist in high school basketball.

FIBA Basketball Court DimensionsFIBA governs international basketball courts. The measurements for FIBA basketball courts differ from U.S. courts because of the difference between our Imperial measurements — feet and inches — and the more standard metric system.

FIBA courts are an even 28 meters long, which converts to almost 92 feet. The 15-meter width converts to just over 49 feet. The tip-off circle is a bit smaller as well, at 3.5 meters in diameter. This difference translates to a radius of about five feet, seven inches.

The key is almost the same size at 5.8 meters long and 4.8 meters wide. These numbers convert to within a few inches of 19 and 16 feet. The basket is 1.2 meters, or almost four feet, in from the baseline, which puts the foul line at 4.6 meters — 15 feet — away. The restricted area under the basket is 1.25 meters or just a shade more than four feet in radius.

The basket is still 10 feet off the ground, which means the biggest difference is the three-point line. At the top of the arc, the three-point line is 6.75 meters from the center of the basket or 22.15 feet. This measurement works out to about 22 feet, two inches. The FIBA three-point line, which has also been adopted by the WNBA, is over a foot and a half closer than the NBA line.

At the top of the arc, the three-point line is 6.75 meters from the center of the basket or 22.15 feet. This measurement works out to about 22 feet, two inches. The FIBA three-point line, which has also been adopted by the WNBA, is over a foot and a half closer than the NBA line.

The History of Basketball Court DimensionsSince its invention in 1891, basketball’s court dimensions have varied. Let’s look at some of its historical changes, as well as answering that nagging question — “Why are basketball hoops 10 feet high?” — below:

The Story Behind the 10-Foot High Hoop

It would appear the 10-foot basketball hoop is the result of a careful calculation that considers the human anatomy and mechanics of the game. After all, even the tallest players today have to jump to dunk a ball, and a ten-foot high rim gives a comfortable target to shoot for at a distance. But as we see so often in history, the truth is much more mundane.

When James Naismith dreamed up the game in Springfield, MA in 1891, the railing he chose to hang the baskets on was ten feet off the ground. So, while everything else about the sport has changed since that first game, the baskets are still right where Dr. Naismith hung them.

So, while everything else about the sport has changed since that first game, the baskets are still right where Dr. Naismith hung them.

The History of the Three-Point Line

The three-point line is arguably the most recognizable aspect of a basketball court’s dimensions and part of the reason why is attributed to the history surrounding this semicircle.

The first instance of the three-point line appeared in the American Basketball League in 1961, a full 70 years after Dr. Naismith invented the game. The line was added to increase excitement, but the league folded in just one and a half seasons, so the idea never had a chance.

In 1967, the next competitor to the NBA arrived. The American Basketball Association, or ABA, instituted the three-point line from the very start, and it was a huge success. The ABA had many exciting innovations that produced a better product for the fans. But ultimately, there was not enough room for two professional basketball organizations, so the NBA and ABA merged in 1976.

The three-point line, however, was not included in the merger! The decision-makers in the NBA at the time were too stubborn to adopt such a radical change. They held out for three years before implementing the three-point line in the 1979-1980 season. The NCAA didn’t integrate it until 1986, and it didn’t arrive on high school basketball courts until 1987.

That isn’t the end of the story, however. The line was moved closer for three seasons in the ‘90s to try to boost scoring, but it was quickly moved back to its original place. Taking the idea to the extreme, the NBA has even admitted to having discussions about a four-point line. Ultimately, we’ll believe it when we see it.

The Original Cage Matches

In the early days of professional basketball, the game was played inside an actual cage. The reasons were more about practicality than about safety. The rule for who got to inbound a ball that left the court was “whoever got to it first,” so organizers took to putting up a cage so the ball could never go out of bounds in the first place.

Those first basketball courts were about a third smaller than they are today, and the cages provided a physical boundary and an extra immovable for savvy teams. Could you imagine how much different the game of basketball would be today if those cages had stuck around?

The Alternative Key Designs

Today, basketball courts at all levels share a common design for the key — a rectangle measuring either 19 feet by 16 feet or 19 feet by 12 feet. However, this was not always the case. From the creation of FIBA in 1956 until 2010, the key was a trapezoidal design that was significantly wider at the baseline.

Another design of this feature is responsible for the name “key.” Have you ever thought about how a rectangular area under a basket got such a random name?

The reason is that the original area was much narrower, while the circle surrounding the free throw line was the same size. These two factors combined to create a shape that resembled an old-fashioned key. In 1951, the key was widened to 12 feet and later to the 16 feet we see now in the NBA and FIBA.

In 1951, the key was widened to 12 feet and later to the 16 feet we see now in the NBA and FIBA.

While the term lives on, time has erased any record of its design and original reference. And for the record, the official name for this feature is “free throw lane,” which isn’t a phrase many of us hear often.

And that’s a wrap on the history of basketball’s court dimensions.

Build Your Basketball Court With PROformancePerhaps you don’t have 94 feet of flat asphalt or indoor floor space. Don’t worry, because residential half court setups can be just as fun. And whether you are looking to paint your court or apply a pre-made solution, sticking to the official dimensions will take your pickup games to the next level.

Take a look at our selection of goals, nets and accessories to bring your home’s court together. You’ll have a hard time dragging your kids off the court as they spend hours posting up like Boogie, slashing like LeBron and launching it from deep like Steph.

Basketball court markings: standards and norms

Author of the article

Khvatkov Dmitry

Consultant in the production of rubber coatings

Basketball field marking requirements are approved by the FIBA standard. The site must be flat with a hard surface, free of bends, cracks and other obstacles. The accepted dimensions of the field are 28 m long and 16 m wide. By NBA standards, the field is slightly larger: 28.7 m (94' ft) long and 15.3 m (50' ft) wide.

Areas not intended for international competitions may differ from accepted standards (for public use, in schools or universities, etc.) and usually vary from 20 to 28 m in length and from 12 to 16 m in width.

Basketball Court Marking Standards

Basketball court markings are conventionally divided into 5 components:

- Boundary lines. They are located along the perimeter of the site and set its size. The lines that run along the field are called side lines, and those that are behind the baskets are called front lines.

- Central line. Divides the court in half parallel to the front lines.

- Central zone. It is a circle and is placed in the middle of the center line, and, accordingly, in the center of the entire field.

- Three-point line. It is a semi-ellipse and is located around the shields on both sides of the field. It limits the close range.

- Free throw line. It is located in front of the boards parallel to the front line and is limited on the sides by paint lines.

The standard line width is 5 cm. All outlines and lines must be of the same color (usually white) and be clearly visible from anywhere on the court.

Common lines

Common lines are used to limit the playing area of the court. The side lines (along the field) according to FIBA standards should be 28 m long, and the front lines - 16 m. For public areas, deviations from the accepted standards are allowed. Typically, basketball courts in schools or gyms are made from 20 m long and 12 m wide.

Central lines

The center line is parallel to the front and divides the field exactly in half. According to the standards - it should extend beyond the side lines by 15 cm on both sides.

In the middle of the center line there is a circle with a diameter of 3.6 m, which limits the central zone of the field. In this zone, the ball is played at the beginning of the game.

Three-Point Line

Three-Point Lines are located around the backboards on both sides of the field and consist of two straight lines 2.9 long9 m and a semicircle. Straight lines run perpendicular to the front at a distance of 0.9 m from the side lines. Despite the fact that visually the distance from the ring to the side of the three-point line seems to be less than to its central part, the distance from the backboard to any point is 6.75 m.

Penalty lines

Penalty lines limit the nearest area at the backboard. They consist of a trapezoid and a free throw zone.

Despite the name, the "trapezium" is a rectangle (until 2009year it really was a trapezoid), which is located under the shield. Its dimensions are 5.8 meters long and 4.9 meters wide. The shield is located at a distance of 1.575 m from the end line in the middle of the court. In front of the backboard, at a distance of 1.25 m, there is a semicircle that limits the area for picking up the ball.

At a distance of 4.225 meters from the backboard, the trapeze zone ends and the free throw zone begins. It is a semicircle with a diameter of 3.6 m (like the central circle).

Paint zone lines

These lines are serifs on both sides of the trapezoid (parallel to the side lines). They limit the areas for players who are fighting for the ball during a free throw.

Zones on the basketball field

The basketball court is divided into zones using markings. Each zone has its own specific rules.

Center circle

The center circle is used as a separate kick-off area at the start of the game. One representative from each team stand in a circle from their side and fight for the ball in a jump, after it is dropped by the referee. All players are exclusively on their side of the field, except for one who rebounds on the opponent's side.

One representative from each team stand in a circle from their side and fight for the ball in a jump, after it is dropped by the referee. All players are exclusively on their side of the field, except for one who rebounds on the opponent's side.

Neutral zone

The peculiarity of this zone is that as soon as the player of the attacking team with the ball crosses the center line and is on the side of the opponent, he cannot pass the ball to the player of his team who is on the other side of the field (i.e. behind center line on your side).

Three-point zone

The three-point line limits the near zone of the shot. Hitting the basket from outside the basket brings the team three points. If the throw was made inside the zone, then it brings two points.

Three-second zone

This is the zone in close proximity to the ring. It is called three-second, since the player of the attacking team cannot be in it for more than three seconds. Most balls are thrown in this zone, so when attacking, it provides maximum protection.

Free throw area

In controversial situations, a free throw is provided from this area. The player of the attacking team must score the ball without stepping over the line of the trapezoid. At the same time, the players of both teams are not in the three-second zone. They take up positions along the paint lines on the sides of the trapezoid and may not step outside the lines until the free throw shooter has shot the ball.

How to mark a basketball field?

Basketball field markings, whether it is an international competition court or an open-air amateur field, are best applied using special equipment. This will ensure the long life of the coating, the lines will not clog and will promote fair play.

You can order the marking of a basketball court in Moscow and the Moscow region from Rezkom. We will measure the premises and develop a design project for the field so that it complies with generally accepted rules and is convenient for operation. For more details, you can contact our manager by phone 8-495-64-24-111.

Three-pointers are killing basketball. We need to do something about it, immediately - Bank shot - Blogs

Basketball Greta Thunberg warns.

Translation of key points from the book Kirk Goldsbury's Stretch Era: A Visual Tour of the Modern NBA

It's undeniable that the introduction of the three-point line on the basketball court has completely changed the game. Exactly 40 years have passed since then - the NBA has lived longer with an arc than without an arc.

With the exception of a short three-year stretch in the 90s, the three-point line has remained roughly the same. Interestingly, the modern design of the court has existed for much longer than any of its previous configurations.

The problem is that for many of us three-pointers are losing their appeal. Snipers are too good and feel too at ease, and long-range attempts are becoming more and more numerous.

Here's an insane number: in the 2017/18 season, the NBA made 25,807 three-point shots. This is more than in the entire 80s. Between 1979 and 89/90 seasons in the NBA put 23,871 three-pointers.

Throughout its history, the league has shown an impressive willingness to change the rules and layout of the court to make the game more varied and interesting.

In 1947, when the league banned zone defense, one of the main defensive tactics disappeared.

In 1950, to get rid of rudeness and unsportsmanlike fouls, the league introduced dropped balls after every free kick scored in the last three minutes—rather than simply giving possession to the team that broke the rules.

In 1951, the so-called Mikan rule changed the face of the basketball court by doubling the three-second zone from 6 to 12 feet to reduce George Mikan's unprecedented dominance.

13 years later, in 1964, the league extended the 3-second again to 16 feet, this time to influence Wilt Chamberlain's dominance.

And now, 55 years later, it is still the same size.

These two "extensions" are interesting to look at for several reasons.

First, they show that the league has always changed the layout so that one particular element or one particular style of play does not become dominant . NBA basketball is constantly changing, and while some of the transformations have been natural, some have been engineered by generations of legislators in the NBA office. Like the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, the building is already incredible, but continues to evolve all the time: professional basketball is never perceived as a finished product.

Second, these two decisions to expand the three-second time limit show that the league's most daring rule changes were aimed at making life harder for the "big ones" - and making life easier for the "little ones" . Looking at modern basketball, where there are fewer and fewer real centers and power forwards, it is very difficult to imagine that once it was the “big” ones who were the main participants in this show, and the small players played limited roles.

Between 1946 and 2018, the NBA consistently changed the rules to move away from the tough game of the "big" in favor of the perimeter-oriented game of the small. And while you can see the small five as a product of analytical genius, the truth is that modern aesthetics and trends in professional basketball have little to do with analytics, but seem to be the culmination of a 70-year prejudice against the big. The three-point arc is just one example.

George Mikan revolutionized basketball. He became an example for the next generations of the NBA and laid the aesthetic foundations for the entire sport. In the next 30 years, basketball was dominated by a whole bunch of centers who took a cue from the trailblazer, rushed into the low post and stormed the shield. Guys like Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain were champions and MVPs, the teams with the best centers had the best chance of winning. The league's early superstars were almost all shaped like Mikan, and the league continued to influence their play. Wilt Chamberlain was so athletic that he could immediately shift the misses of the partners into the ring - and then the league introduced a rule that it was forbidden to touch the ball before it left the cylinder of the ring. At 19The 64th was followed by an expansion of "paint".

Wilt Chamberlain was so athletic that he could immediately shift the misses of the partners into the ring - and then the league introduced a rule that it was forbidden to touch the ball before it left the cylinder of the ring. At 19The 64th was followed by an expansion of "paint".

The league came up with the Most Valuable Player award in 1955, after which the centers began to win it almost every year. Of the first 24 trophy winners, forwards took only two or three (depending on who you think Bob McAdoo is), and defensemen only two. Centers - 19 or 20. You understand what I want to say. It was the big league. After Maikan, it became clear that the center is the most valuable position on the court.

But Maikan didn't finish changing basketball.

In the 1960s he did it again, now as a commission agent.

In 1967, he became the first commissioner for the ABA, a new league that tried to compete with the NBA. To achieve this goal, he had to come up with all sorts of tricks that would attract the attention of fans and make basketball more attractive. He got a few. First of all, he added a red-white-blue ball - he thought that such a ball would look more spectacular than the orange-brown version that was used in the NBA and NCAA. The kids really liked it a lot. But that wasn't enough. We needed another crazy idea that would make the game more unpredictable. And so he revived the idea of the "three-point shot," which was first used in the American Basketball League in early 1919 without much success.60s.

He got a few. First of all, he added a red-white-blue ball - he thought that such a ball would look more spectacular than the orange-brown version that was used in the NBA and NCAA. The kids really liked it a lot. But that wasn't enough. We needed another crazy idea that would make the game more unpredictable. And so he revived the idea of the "three-point shot," which was first used in the American Basketball League in early 1919 without much success.60s.

What is the American Basketball League? This league was born in 1961 and lasted only two seasons. Her commissioner was Abe Saperstein, a man remembered not for running the failed ABL but for starting the Harlem Globetrotters. Saperstein was half showman, half basketball visionary.

In the early 60s, John F. Kennedy was president, the space race between the USSR and the USA was just beginning, and the Americans did not leave their TV sets and followed the Cuban Missile Crisis. Baseball was then the most popular sport in the country, and the most popular athlete was Roger Maris. He captivated fans across America by breaking all records for the number of home runs. In the fall of '61, Maris broke Babe Ruth's all-time record when he hit his 61st home run of the season.

He captivated fans across America by breaking all records for the number of home runs. In the fall of '61, Maris broke Babe Ruth's all-time record when he hit his 61st home run of the season.

Home runs were by far the most exciting element of America's favorite game. There was something so magical about that endless flight of the ball that made baseball fans jump up and down. Those few seconds of flight, everyone in the stadium - fans, players, commentators and coaches - were waiting for where this rocket would land. Home runs not only created tension and attention, they also had a huge impact on the course of the game - this is the fastest way to make a "run" in baseball. It was the best in American sports.

So it's no coincidence that Abe Saperstein's revolutionary idea came in 1961 in a country that was going crazy with rockets, long-range bombs, home runs and gunshots going around the world.

Saperstein asked himself what would be home runs in basketball? What would it look like?

He came up with an insane variation on the "home run throw" that was similar to what Maris did: the longest shot and the fastest way to score. Also keep in mind that during Mikan-Russell—the first 20 years of the NBA—most shots were made close to the rim. It made no sense to throw from a distance, as such throws were more difficult and less effective. Wilt Chamberlain rarely threw from three meters, let alone 6.5.

Also keep in mind that during Mikan-Russell—the first 20 years of the NBA—most shots were made close to the rim. It made no sense to throw from a distance, as such throws were more difficult and less effective. Wilt Chamberlain rarely threw from three meters, let alone 6.5.

Saperstein consulted with the players and coaches and agreed with them to create a three-point arc. Where did he place it? Exactly where you see her today. 22 feet in the corners, 23.75 feet in the rest of the area. Madness, right? This happened almost 60 years ago. What are the chances that the optimal distance for the arc during Chamberlain is the optimal distance during Steph Curry's time?

And yet, if not for Mikan and the ABA, most likely the idea of a three-point arc was born and would have died along with the ABL, which lived for two seasons. The ABA and the three-point shot changed the history of basketball forever. Alex Hannam, who led Philadelphia to an NBA title in 66/67 and Oakland to an ABA title in 68/69, immediately noted the influence of the line and how it opens up the court: “In the NBA, we just hammered the central zone and forced the teams to attack from afar. No one was going to keep anyone five meters from the basket, but three-point threat changed everything. Someone starts to hit from a distance and score not two, but three points, and the coaches are forced to change the strategy - and defense. No other rule made the game so open, so fun .”

No one was going to keep anyone five meters from the basket, but three-point threat changed everything. Someone starts to hit from a distance and score not two, but three points, and the coaches are forced to change the strategy - and defense. No other rule made the game so open, so fun .”

Hannam was right. The Saperstein line didn't just give basketball home runs, it opened up the entire court. She made basketball less contact, helped to get away from the flea market. Passes were now given over longer distances, throws from a distance became more spectacular. The ball was more often in the air, moved more. Just like the players themselves. All of a sudden there was more room for players to show off and more ways to score. The ABA has taken Saperstein's vision and enriched basketball.

Largely because of the three-point arc, the ABA immediately showed differences between themselves and the NBA. The arc affected every possession, even those that didn't make it to 3-pointers. The players ran around the court a lot more, the ABA games were more fun, they gave the attack more room to shine, and they played at a faster pace. The NBA remained the more successful league and retained all the talented players, but compared to the ABA, it looked conservative and rigid. Hardcore backfield play continued to dominate there, and the philosophical divisions between the leagues only deepened as the decade progressed, until the NBA was left with no choice but to bring the three-point line to its courts as well.

The players ran around the court a lot more, the ABA games were more fun, they gave the attack more room to shine, and they played at a faster pace. The NBA remained the more successful league and retained all the talented players, but compared to the ABA, it looked conservative and rigid. Hardcore backfield play continued to dominate there, and the philosophical divisions between the leagues only deepened as the decade progressed, until the NBA was left with no choice but to bring the three-point line to its courts as well.

In 1976 the leagues merged. The NBA accepted four teams from the ABA, the other three closed. A few years later, despite the protests of Celtics president Red Auerbach, the NBA added a three-point arc and placed it exactly where Saperstein intended it to be, 22 feet in the corners and 23.75 feet in the arc.

There she remains to this day.

Maybe it's time for a change. Mikan once brought the 3-point line into the ABA to "give the little players a chance", but now the big players - Mikan's heirs - need that chance. In fact, in 2018, big players are less visible than small ones before the introduction of the arc. Curiously, centers weren't on the court during major episodes of the past decade. For example, in the 2016 finals, Cleveland and Golden State rarely used centers: both Andrew Bogut and Timofey Mozgov almost never went to the floor. And in the main series of 2018 - the series between the Rockets and Golden State - Houston missed from behind the arc in the seventh game, when they threw 7 of 44. Missed three-pointers are now the main aesthetics of the NBA, and all analytics boils down to the thesis “hit or miss” .

In fact, in 2018, big players are less visible than small ones before the introduction of the arc. Curiously, centers weren't on the court during major episodes of the past decade. For example, in the 2016 finals, Cleveland and Golden State rarely used centers: both Andrew Bogut and Timofey Mozgov almost never went to the floor. And in the main series of 2018 - the series between the Rockets and Golden State - Houston missed from behind the arc in the seventh game, when they threw 7 of 44. Missed three-pointers are now the main aesthetics of the NBA, and all analytics boils down to the thesis “hit or miss” .

Over the past decade, shooting from behind the arc has become the most important skill in the game. Snipers have taken over basketball, and the only ones left in the NBA are the big ones who can shoot—and defend—on the perimeter. Guys like Bogut and Mozgov can do neither, and therefore their value is lower than ever. It so happened that by 2018, Bogut, a huge Australian center, the first number in the 2005 draft and one of the key characters for the rise of the Warriors, was out of the NBA altogether, and Mozgov, at the age of 33, did not succeed much more. Although the Russian big man signed a huge contract with the Lakers in the summer of 2016, he spent several years as an outcast who was transferred from team to team and barely appeared on the court for Brooklyn in the 2017-18 season.

Although the Russian big man signed a huge contract with the Lakers in the summer of 2016, he spent several years as an outcast who was transferred from team to team and barely appeared on the court for Brooklyn in the 2017-18 season.

In parallel with the major changes of the 50s and 60s that neutralized the post game and introduced the three-point arc, the league also made other subterfuges to help reduce the value of the traditional bigs. At the same time, while in the early years the development of the NBA constantly changed the rules and moved the markings, today's NBA is in many ways reminiscent of the modern Congress - it absolutely cannot not only introduce, but even propose at least some change.

Now it's a league where stretchy skinny guys like Ryan Anderson and Channing Fry are more valuable than stupid dinosaurs like Al Jefferson trying to attack from a low left post. This is a league where a guy like DeMarcus Cousins, arguably the most physically intimidating man in basketball today, throws as many 3-pointers as Reggie Miller once did. In the 2017/18 season, Cousins made 6.1 shots per game - Miller reached this mark only once in his 18-year career.

In the 2017/18 season, Cousins made 6.1 shots per game - Miller reached this mark only once in his 18-year career.

The two three-second extensions that devalued the power of the big ones and pushed them into the medium throw zone are just the first blow to those whose main contribution is the game in the post. The second hit is the addition of the 3-point line, which brings a circus trick of extra value to the long shot. This stunning combination knocked out the giants and sent them to analytically acceptable reservations near the ring and beyond the arc. The new markings left for the traditional "big" zones that people like Daryl Morey despise - places where you can't break through for a good attack from under the basket and yet far from all the perks offered beyond the three-point arc.

Over the past decades, the "big" and their mid-range attacks have become - not too surprisingly - "less effective". At the same time, both the team's tactics and the work of management are more focused on giving the ball less to the mustache and looking for a sniper on the arc much more often.

While the extensions to the 3-second intentionally reduced the value of underfield play - and the "big ones" - the arc did exactly the opposite for snipers: it increased the value of those who could shoot 3-pointers. An incredible attempt back to the ring, a hook through Joel Embiid's outstretched arms is only two points, and another open throw from a take-throw situation from Danny Green or Trevor Ariza is three points. For anyone who has ever played the NBA Jam, it should be obvious that the number of points scored no longer correlates with the difficulty of the throw.

The pursuit of efficiency is nothing new. It is clear that both Mikan and Chamberlain were extremely effective players for their time. But the modern path to efficiency is dictated by the rules and threatens a variety of play in a way we haven't seen since Mikan and Chamberlain. Today, harnessing the dragon of efficiency means making the most of three-pointers, which leaves vast areas of scoring ground to waste. As in ancient times, a new, albeit different, kind of one-dimensional attack has hit the entire league.

As in ancient times, a new, albeit different, kind of one-dimensional attack has hit the entire league.

This is perhaps the main idea of the modern era: successive rule changes have produced a generation of player coaches for whom the three-point line has redefined the basic economic geography that defines the fundamental principles of basketball. According to these principles, "greatness" and maximum contracts are reserved for players who are able to consistently perform the most impressive tasks at the highest level. But as the 3-pointer becomes one of the biggest and most visible options on the floor, people who can do it in high volumes are becoming "great" even though it's not really a great skill.

As teams, players, and coaches find ways to shoot more and more 3-pointers, the very nature of the game is changing and taking away something important—namely, links to the past. 90,003 90,002 During the '79/80 season, the Rockets made 4.6 3-pointers and 86.8 2-pointers per game. 90,003 90,002 In 2017-18, the Rockets made 42.3 three-pointers and 41.9 two-pointers per game.

90,003 90,002 In 2017-18, the Rockets made 42.3 three-pointers and 41.9 two-pointers per game.

Today's aesthetic is built on three interrelated trends: positional versatility, long-range shooting, and isolation.

As Draymond Green became the dominating figure on Golden State's defense, the Warriors adopted a new defensive philosophy and started trading on every screen—which also reduced the value of screening. Most of their players can defend in multiple positions, but there are a few weak links in Golden State's defense. As Houston demonstrated, all of these defensive exchanges can be exploited by the opposition. For example, the Rockets weakened the Warriors' defense by forcing them to trade early in the attack so that Steph Curry would stay against James Harden. Again and again, Harden played "isolation" against Curry, and the rest of the Rockets created space for him. The whole series turned into a one-on-one game between Harden and Curry, with the other eight guys just watching her from their best positions.

Houston coach Mike D'Antoni defended this strategy and stressed that it worked.

“Everyone is like, 'Oh my god, they're playing isolation! That's all they do." No, that's not all, he said. “That's what we do best. We score points 60 percent of the time. And everyone's like, “Oh my God, they don't play pass. Everyone just stands there." Truth? Have you ever seen us play? This is exactly how we operate. It's our nature, it's what we're really good at."

He was right. These "isolations" not only worked, they were also a natural tactical response to the Warriors' strategy of trading everything on defense. This strategy was only made possible by rule changes and regular refereeing errors that greatly reduced the positional diversity and value of the traditional NBA Bigs.

One of the biggest reasons Green and the Warriors can trade is because their opponents don't have the ability to penalize them for using a miniature center. Roughly speaking, we have reached the point where the optimal one-on-one advantage is achieved between a small player and a slow defender who is forced to go to the perimeter. This is a very strong departure from the norms that created basketball in the first place. For most of the history of the NBA, the optimal one-on-one advantage was achieved under the backboard, where the offensive team would trade a powerful big player against a small, weak defender. Maikan, Russell, Karim, Shaq or whatever - they all destroyed under the shield. But nobody else does that.

This is a very strong departure from the norms that created basketball in the first place. For most of the history of the NBA, the optimal one-on-one advantage was achieved under the backboard, where the offensive team would trade a powerful big player against a small, weak defender. Maikan, Russell, Karim, Shaq or whatever - they all destroyed under the shield. But nobody else does that.

Houston gained a huge advantage every time Harden was left alone against weak defensemen. That is why they used this variant more than 150 times throughout the series. Do you know what they didn't do? They didn't try to take advantage of the shield. Never. Rockets center Clint Capela, this giant dunk machine, flirted in the post 6 times in the entire playoffs and never in a series against Golden State. Why? And why should he? The numbers are pretty clear: post-ups are dumb, it's much more efficient to seek "isolation" for Harden than to give the ball to Capele. During the regular season, Capela had 55 post situations, of which he averaged 0. 92 points. Figovato. At the same time, Harden used 894 "isolations", which brought an average of 1.15 points.

92 points. Figovato. At the same time, Harden used 894 "isolations", which brought an average of 1.15 points.

Lest you think Capela's lack of efficiency is the problem, consider the following. Among the seven players who played more than 500 mustaches in 17/18, Carl-Anthony Towns was the top performer, averaging 1.05 points. That's good, but it doesn't come close to Harden's 1.15-point isolations or the relative efficiency of even a league-average 1.07 three-pointer. In other words, an average 3-pointer thrown by, say, Trevor Ariza, Ryan Anderson, and PJ Tucker is a better option than a post-up shot by the best post-up artist in the league. No wonder, then, that the game under the shield is dying, and the cause of death lies in inefficiency, in the most terrible disease of our era. Look: in the 2013/14 season, 22 NBA players flirted under the shield at least 500 times. By the 2017/18 season, only eight of them remained. In the 2013/14 season, five players entered the post at least 1,000 times, by the 2017/18 season, only one remained - LaMarcus Aldridge.

While the league has essentially fought the bigs at the legislative level since Mikan, maybe - just maybe - during Curry, Morey and endless lockdowns and 3-pointers after receiving it, it's time to move on from that. Perhaps since we're in an era where centers and shield play are close to extinction, we need to resort to our own version of the Endangered Species Act and roll a couple of dice to the giants. Except during the biggest stylistic shift in basketball history, the league suddenly does nothing and instead maintains all the same conservative trends that led to the current state of affairs in the first place. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the NBA is more popular than ever. Perhaps because only such old grumblers like me are unhappy with the rise of the three-pointer and the monotonous monotony of attacks.

Decades after Saperstein and Mikan, three-point shots determine the outcome of more and more matches. Revisit the ending of Game 7 of the 2016 Historic Finals. At the key moment of the main meeting of the decade, Golden State and Cleveland simply exchanged three-pointers. In the two-point shot zone, nothing happened at all. The pendulum has swung from the rim to the 3-point arc, and for some of us, the average NBA possession, in which three guys just stomp around the corners or around the edges, loses its magic.

At the key moment of the main meeting of the decade, Golden State and Cleveland simply exchanged three-pointers. In the two-point shot zone, nothing happened at all. The pendulum has swung from the rim to the 3-point arc, and for some of us, the average NBA possession, in which three guys just stomp around the corners or around the edges, loses its magic.

Saperstein's "home run" has become so common that few people jump from their seats. In 2017, the Houston Astros became champions - they also hit the most home runs, averaging 1.47 per game. Their 2018 NBA counterparts, the Rockets, led the NBA in 3-pointers, averaging 42.3 per game. Once upon a time, three-pointers gave novelty, for half you could see only a few attempts, now they are realized on average every minute. Are three-pointers still amazing when they come in every minute?

A rise in three-pointers means a decrease in two-pointers. Some of us lack the momentum and athleticism needed to score inside the arc. For example, I would like to see fewer three-pointers from PJ Tucker and more deflected shots from Michael Jordan, dreamshakes from Hakim and hooks from Abdul-Jabbar.

An increasingly monotonous aesthetic correlates less and less with the geniuses who shape the strategy of the game, and more and more with the fact that the league fell asleep at the wheel while the bus slowly moves into a uniform ditch of endless three-pointers . In 2019, a long-range shot after a pass is about as unique and exciting as playing under the shield in 1978. The same factors that forced the expansion of the three-second in the 50-5 and 60s should be the impetus for new changes: aesthetics, tactical diversity and entertainment aspect.

Call me old fashioned, but my favorite teams are the Heat and the Spurs of the 2010s. For me, the movement of the ball and the tactical variety of the 2013 and 2014 finals are priceless. Those series featured future Hall of Famers Tony Parker, Tim Duncan, LeBron James and Dwyane Wade—phenomenal players who reached the highest level and won the Final Series MVP title and did so without three-pointers. Their greatness declared itself within the arc. Those teams are not that in every attack they tried to smuggle the ball under the shield. The ball was moving at a crazy speed, and each team had amazing long-range artillery specialists Danny Green, Shane Battier and Mike Miller. Those matches were great.

Those teams are not that in every attack they tried to smuggle the ball under the shield. The ball was moving at a crazy speed, and each team had amazing long-range artillery specialists Danny Green, Shane Battier and Mike Miller. Those matches were great.

But here's a paradoxical thought for you: if we like the way basketball looks this decade, we should advocate for rule changes that would slow down or even limit the league's increasing craze for 3-pointers.

We must support change that develops the variety of aesthetics and athleticism that has been at the core of basketball since the days of Bob Cousy and Bill Russell.

But what can be changed?

Every time the NBA has faced an aesthetic crisis, it has changed the rules to adjust the visuals of basketball.

Basketball is at its best when different types of players can perform differently. Since the start of the game, five different positions have emerged organically: point guards, shooting guards, small forwards, power forwards and centers. One way basketball protectionism is to keep each of these unique species alive is to create a balanced version of basketball in which each is important in its own way.

One way basketball protectionism is to keep each of these unique species alive is to create a balanced version of basketball in which each is important in its own way.

There is no such vision in the modern NBA. Centers are disappearing, wingers are becoming power forwards or, more accurately, stretching fourths, and backboarding, once the dominant offensive tactic, is heading in the same direction as MySpace. The average NBA game consists of 60 three-pointers (the number is rising) and less than 20 post-shots (the number is falling) .

So what options do we have?

Transfer line!

The League impacted Mikan and Chamberlain's prime years with a major rule change designed to dampen their offensive power. In both cases, the league made changes not only to reduce the effectiveness of their play in the post, but also to ensure that they attacked less often. The changes were connected not only with dominance, but also with aesthetic considerations.

Based on this, the league should try to transform the shape and location of the three-point arc.

First of all, why is the line where Abe Saperstein placed it in 1961, almost 60 years ago? Then only a few players could get from there, today almost all of them.

Move it 7.5 meters away from the ring?

The simplest change is to move the archwire.

For three seasons in the 90s, the league moved the three-point line closer as an experiment. By the end of this period - by season-1996/97 - 3-pointers made up 21% of field goals. The next season, the league moved the arc back to its original position, half a meter back, presumably because the number was too high. The figure has dropped to 16 percent.

We can also learn from the WNBA. The league moved the arc to a distance of 0.5 meters, which corresponds to the distance provided for by FIBA rules. The results were immediate: in the previous two seasons, 25.3% of field goals were converted from behind the arc, the league as a whole sold 35. 2% of such shots. When the arc was pushed back, these figures fell to 21.5% and 32.7%, respectively.

2% of such shots. When the arc was pushed back, these figures fell to 21.5% and 32.7%, respectively.

In both cases, this affected the effectiveness and the frequency of long attempts, and thus returned the emphasis to two-point attacks. If the NBA moves the arc by 7.5 meters, it will likely bring about similar changes. During the 2013/14 regular season, NBA players threw 52,000 three-pointers. More than 25 thousand - from a distance of more than 7.5 meters. In general, such throws were realized with an accuracy of 34.5 percent, compared with 38.4% from a distance closer than 7.5 meters .

As you can see from this graph, the number of three-pointers went down only when the league moved the arc back to its original position. It is likely that something similar will happen again. The retries will go down. Efficiency will go down. The value of snipers will go down. Two-pointers will again be significant and tactically in demand. The players of the post will return respect.

The good thing is that we can now use all of these examples to predict how moving the NBA line 7.5 meters will affect shooting behavior in the NBA. It’s bad that a distance of 7.5 meters is still a subjective decision. Why 7.5? Why not 7.5? Why not 8?

Why not move the arc to match the analysis we have?

Here's an interesting fact: on average, a field goal scores almost exactly one point. What an amazing analytical coincidence!

The invention of the 3-point arc made 33.33% the magic number in the NBA. Anyone who can convert a third of his long shots will average one point per possession. This is the same as converting half of two-point attempts. But over time, sharpshooters have progressed and come to realize 36%, and the best of them regularly lay 40%. This is the same as converting 60% of 2-pointers .

A small increase in efficiency and a huge increase in the number of players that can deliver that efficiency at high volumes are the two defining factors of the new era.

These bursts of efficiency may seem small to individual players, but at a league level they are amazing. When shooters in general put 36% of three-pointers, the attitude towards such shots changes. There was a time when 3-pointers weren't the best shot for most players in the league. It's long gone. Now we have data that helps to determine with great accuracy where exactly snipers attack from better. And on the basis of such data, you need to determine the distance by which you need to move the three-point line. We need to figure out where the league is going to hit exactly one-third of all 3-point attempts.

The graph provides two key insights:

1. There is a correlation between distance and hit percentage, but it's not as strong as you might think.

2. Across the league, the closest 3-pointers—those from the corner—are shot within 40%. Given that two-pointers from three meters away are shot with 40 percent accuracy, why would anyone shoot a two-pointer at all?

But the graph does not answer the key question: where should the line be for three-point attempts to hit 33. 33%? It's a tough question, but after looking at almost 70,000 3-pointers from the 2017/18 season (which excludes home-field shots), some estimates can be made. NBA sharpshooters made 33.33% of their long shots from 7.8 meters, exactly two feet from the three-point arc.

33%? It's a tough question, but after looking at almost 70,000 3-pointers from the 2017/18 season (which excludes home-field shots), some estimates can be made. NBA sharpshooters made 33.33% of their long shots from 7.8 meters, exactly two feet from the three-point arc.

So why not move the arc based on this analysis?

The cool thing is that we can update this data every year. The qualifications of snipers change, and the arc can also move in accordance with it. Each summer, we will study the data from the past season and move it accordingly, focusing on specific data. Three-pointers will always be worth one point per possession. Everyone's long shot percentage will suffer, but the best shooters in the league will still be valuable, in fact, they will be much more valuable.

And fear not: Steph Curry will continue to be among the MVPs. In 2017/18, 36 people made at least 100 three-point shots from 7.8 meters from the rim, but only one made more than 40% - Curry had 43. 6% of 172 three-point shots made outside the hypothetical arc.

6% of 172 three-point shots made outside the hypothetical arc.

In contrast, those who are not very good will become less valuable with the new line, and their ability to "stretch the court" will suffer. For example, Andrew Wiggins only made 22.8% of his 123 3-pointers in the 2017/18 season. Defenders will not pay attention to him at this distance.

Many of the most active shooters in today's league are already marginally effective, and if the line is moved back, they will go into the red. The number of players focusing on three-pointers will decrease, and the league will need to be more careful about the two-point zone and those who can benefit from there. Channing Fry would have to work hard. Some 3-pointers would lose playing time, deviated shots would be back in vogue, and there would be more variation in different types of shots. Many three-pointers would turn into "bad shots." And all this would have happened thanks to analytics - Mori would have been bitten by his own snake.

Get three-pointers out of the corner

Ray Allen's incredible shot in Game 6 of the 2013 Finals is arguably one of the best shots in league history. Enough has been said about that shot and how Ray carefully moved to his favorite spot, received a pass from Chris Bosh there, and with a merciless move equalized the score. But here's what's interesting. The place where Ray made the throw - that tiny corner near the front - is usually considered "the smartest shot in the game." In fact, this is the most stupid throw in the game.

Analytically, a three-pointer from the corner should not exist. It stems from a mistake, from a seemingly insignificant provision passed in 1961 that has affected every possession in the NBA ever since. Why on earth does a three-point arc include two straightened fragments?

The three-point line is 23.75 feet everywhere, and only at the corners does the arc straighten out and remain 22 feet from the hoop. Based on this markup, some throws from 23 feet are worth two points, while others are worth three points. From all angles, throws from 22.1 feet are worth two points, but near the front, for some unknown reason, they are worth three. You don't have to be Billy Bean to know this doesn't make any sense.

From all angles, throws from 22.1 feet are worth two points, but near the front, for some unknown reason, they are worth three. You don't have to be Billy Bean to know this doesn't make any sense.

Platform width - 50 feet. The place in the corners is modeled to leave three feet of space for snipers. After all, the guys in the NBA are giants with huge feet and it takes time for them to catch the ball and make the shot. If the arc were 23.75 feet at all levels, then throwers would have 15 inches left, which is clearly not enough for Matt Bonner's sneakers.

Although 3-pointers from the corner make up only 10 percent of shots, they affect nearly every possession. It's as if the minimal solution of cutting the arc in the corners has completely changed the aesthetics of the NBA. Not only do teams and players constantly use this space for shots, but they also use the space to stretch the defense. Stretch guard now implies that the player is stomping away from the ring in one place. It does nothing, but this function is incredibly valuable. For the most part, 20-40 percent of offensive players in the NBA do nothing but chill in the corners. And at the same time, they have a huge impact on the game - they attract defenders to themselves and do not give those opportunities for safety net.

It does nothing, but this function is incredibly valuable. For the most part, 20-40 percent of offensive players in the NBA do nothing but chill in the corners. And at the same time, they have a huge impact on the game - they attract defenders to themselves and do not give those opportunities for safety net.

Not for the first time in history, almost immobile players affect the aesthetics of the game.

Prior to the adoption of the Mikan rule, players pushed close to the ring, where defenders and attacking players fought for space and were not going anywhere. Rule changes like three seconds and illegal defenses were deliberately designed to force basketball players to move and leave their favorite spots. Today, in the era of three-point basketball, the favored points have moved to the arc. But for some reason no one cares. The league has been ruthless about standing inside, but completely oblivious to standing in corners.

This is yet another example of how tough the league has been on the "big" ones and how flippant they are about their little counterparts.

Stand-up corner shooters essentially turn many NBA possessions into a three-on-three game. Players in the corners and their guardians turn into extras - unless, of course, one of the defenders tries to go to safety net against the passing one. In this case, a three-pointer from the corner arrives after the pass and the discount.

But is it interesting? Does anyone even come to an NBA game to watch people stand in the corners of the court?

One easy way to bring more movement to basketball and breathe life into a two-point game is to have smaller boys hanging out at the front. Pushing the arc 23.75 feet won't completely eliminate three-pointers from corners, but it will at least close a gap in basketball rules. Between 2013/14 and 2015/16, the NBA shot 44,000 three-pointers from the corner, or 7.3% of all shots. In general, they were implemented with 39 percent accuracy and brought 1.16 points per throw, this is a very high efficiency for a throw .

At the same time, 36.79% of all attempts were made from areas in the corners where the arc did not straighten - at a distance of 23.75 feet from the ring. This is fully consistent with the throwing efficiency from other areas behind the arc.

At the same time, most of the three-pointers from the corner fell on short sections - 91.4 of all three-pointers from the corner.

So what happens if you remove the loophole?

1. It will be more difficult for snipers, and this will encourage them to move more and not stand in the corner. A distance of 23.75 feet across the entire arc would fit within the modern court, but leave little room for a throw. Since these guys have huge feet, they will be uncomfortable shooting from this area - and they will go to where it will be easier for them to find the necessary balance, time and opportunity to shoot.

2. There will be fewer three-pointers from the corner. Worst of all will be constant questions: was there a spade or not? This will lead to even more tedious repetitions that no one will like. As a result, the court can be expanded - from 50 to 54 feet - but this will be a headache for each arena, since it will require changing the placement of the front rows.

As a result, the court can be expanded - from 50 to 54 feet - but this will be a headache for each arena, since it will require changing the placement of the front rows.

3. Three-pointers from the corner will be less effective.

Enter Special Lines

Warning: this is one of the dumbest ideas I've ever come up with. But some have told me she's great.

What if each team placed the three-point line wherever they wanted?

Since the birth of basketball, the courts in all places have been the same size. This regularity is what distinguishes basketball from baseball and football, which have different markings in different arenas.

Now imagine what it would be like if different NBA teams could place the three-point arc differently? And focus on the strengths and weaknesses of your composition?

One could imagine Golden State moving the arc closer to hit more 3s. At the same time, all their snipers feel great far from the ring: Curry, Durant and Thompson easily hit from 7 meters. If they moved the line there, they would thus force the opponent to play in uncomfortable conditions for themselves.

If they moved the line there, they would thus force the opponent to play in uncomfortable conditions for themselves.

Other teams could change the configuration of the arc and thereby confuse the opponent.

What if some team wants to remove three-pointers from their floor?

This would suit a team with a dominant center like Hassan Whiteside, a team like Miami. Without a three-pointer, the opponent would have to replay the Heat under the basket.

Allow 3-point hitting

This may sound crazy – maybe it is – but basketball was originally allowed to hit balls on shots. Because George Mikan did it too well and became the best defenseman, the league changed the rules and landed the hardest hit on the centers. But the madness is also the addition of a three-pointer. If we allow the ball to be dropped on long shots, we will help the centers and breathe life into two-point attacks.

It will be the same as Kevin Garnett did, who knocked down balls after the whistle, but only during the game. Every time someone throws a long throw, under the basket the guys will fight not only for the rebounding position, but also for the blocking position. It will become much harder to make open three-pointers. Snipers like Korver or Ariza will have to not only shoot at the basket, but also take into account whether their shots can be blocked by a post under the basket.

Every time someone throws a long throw, under the basket the guys will fight not only for the rebounding position, but also for the blocking position. It will become much harder to make open three-pointers. Snipers like Korver or Ariza will have to not only shoot at the basket, but also take into account whether their shots can be blocked by a post under the basket.

One can imagine Jeff Van Gundy exclaiming, “What was Ariza thinking? He threw the ball when Rudy Gobert took a position near the ring!

Centers will regain their value, and small fives will lose their meaning, as sharpshooters will no longer be able to be as effective. Basketball will become more athletic, there will be more struggle at the ring.

The ability to swipe long shots will add tension: not only will everyone be watching the 3-point parabola, but at the same time what the big players are doing near the basket.

Also, this will restore the value of medium rolls, where players can roll and not worry about some monster swiping them at the last moment. So long two-pointers will no longer be the worst attempts on the court, the importance of post players, those who can make attempts with deviation will return ... should we revise the rules that were designed to limit the game of Mikan and Chamberlain? After all, teams no longer load the ball under the hoop.

So long two-pointers will no longer be the worst attempts on the court, the importance of post players, those who can make attempts with deviation will return ... should we revise the rules that were designed to limit the game of Mikan and Chamberlain? After all, teams no longer load the ball under the hoop.

What if we convert the three-second zone back into a "key" and return it to its original shape?

Many fans are more open to rule changes when it comes to getting back to the roots of the game. If we make the "paint" narrower, then this can give impetus to more involvement of the "big ones" in the freed space.

Firstly, this will obviously give the big attackers more options within a few feet of the hoop, making it easier for them to score.

Secondly, the teams will need to pay more attention to the protection under the basket.

The three second is now 16 feet wide. What if you reduce it to 6 or 12 feet? Recall that it was increased due to the fact that Wilt destroyed everyone under the shield. But now there are no Wilts left. We have legally abolished them.

But now there are no Wilts left. We have legally abolished them.

Now it's easy to find Stephs and Clays, Hardens and Westbrooks, but no Wilts, Shaks, Mikans or Karims. Hell, even the McHales are gone. Instead, people like Draymond Green become dominant defenders.

Revise contact rules