Home »

Misc »

How to say basketball in sign language

How to say basketball in sign language

From Thailand to the Basketball Court, Jean Massieu School of the Deaf Student Has All the Signs of a Champion

Mar 02, 2020 10:55AM ● By Katy Whittingham

Sophmore, Eh Ta Kpaw Say, sits down for a conversation in the library of Jean Massieu School of the Deaf campus in Millcreek. (Photo by Susan Thomas/USDB)

By Katy Whittingham | [email protected] cityjournals.com

Eh Ta Kpaw Say is a 10th grader who attends Jean Massieu School of the Deaf in Millcreek. Like many other 10th grade boys, Eh Ta enjoys spending time with his friends, staying active, and especially loves basketball. On the day of our interview he was headed out with his team on a four-hour drive to play a game against a school for the deaf in Idaho, only to turn around and return that evening near midnight or later. “I will be tired,” he admitted, but it’s clear the sport ranks high among his many passions. “I love to learn,” he said several times, and “I want to do everything!”

Now 15, Eh Ta moved to the United States from Thailand when he was 8 years old.![]() He first attended a public school, but then transferred to JMU. He has elected to stay at JMU simply because he “loves it” and enjoys learning from and chatting with teachers, in particular his favorite teacher, Frances Sorrentino, an ASL specialist. “I want to be just like her,” he said, because of her teaching style, his love for her ASL, and she is nice, supportive and entertaining.

He first attended a public school, but then transferred to JMU. He has elected to stay at JMU simply because he “loves it” and enjoys learning from and chatting with teachers, in particular his favorite teacher, Frances Sorrentino, an ASL specialist. “I want to be just like her,” he said, because of her teaching style, his love for her ASL, and she is nice, supportive and entertaining.

One of seven children, with two brothers and four sisters, one of whom sadly passed at 6 years old, Eh Ta speaks three languages: his native Karen /kəˈrɛn/, English and American Sign Language (ASL). He does have some hearing but doesn’t always hear all sounds and misses some of what is spoken to him even at home. For example, he explained that a T sometimes sounds like a D to him.

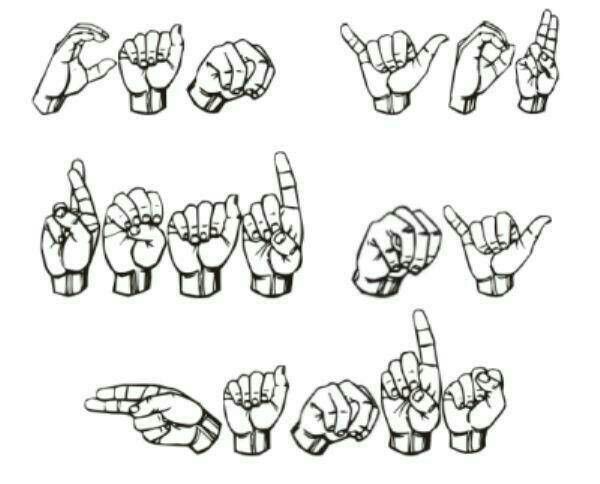

For our interview, he chose to communicate with me using ASL through an interpreter, and then spoke a few times for clarification, especially when he was excited. He noted also that facial expressions are important to ASL, and that it is a very expressive language overall.

He speaks primarily English at home, except with his mother with whom he speaks mostly Karen, and with the exception of a few extended family members, he does not use ASL because they have little to no fluency with it. At school, however, Eh Ta only uses ASL so as not to exclude anyone there, explaining it would be both disrespectful and rude to speak around others who could not understand.

Respect seems to be a part of Eh Ta’s foundation and very important to him. In his early years in Thailand, he preferred talking and interacting with adults, and he wasn’t as interested in making friends with children his age. Moving here, he realized the cultural expectations, and he has become very social and interactive with his peers.

He admits it was difficult when he first came to the United States to make friends, but he took it one step at a time. Aside from socializing through basketball, Eh Ta also loves physical education class for the opportunity to play sports with others and keep his body moving, and even math, which he calls “fun and something to share with friends. ”

”

Eh Ta plans to attend a four-year university after graduation and try out for the basketball team, and if he doesn’t make the team, stay involved with athletics in some way and keep learning. A quest for knowledge is certainly something this sophomore thrives on.

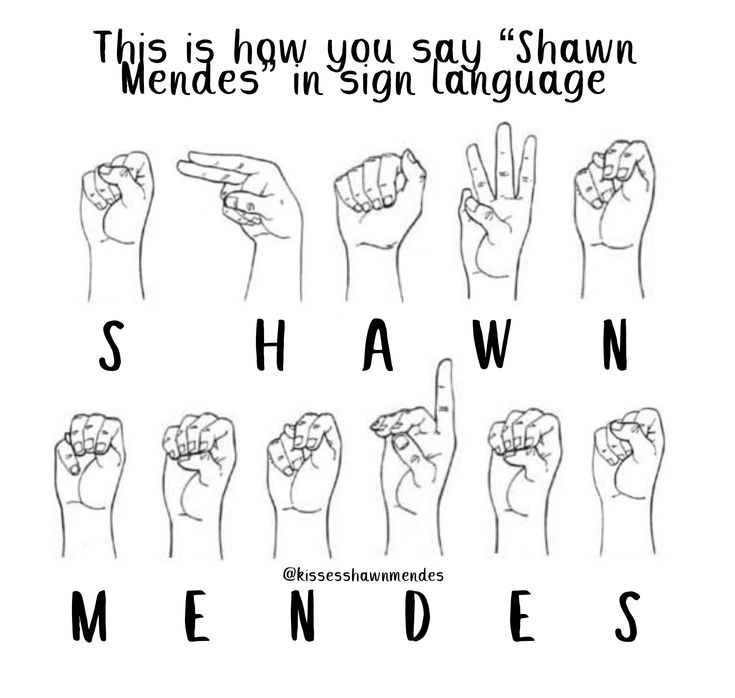

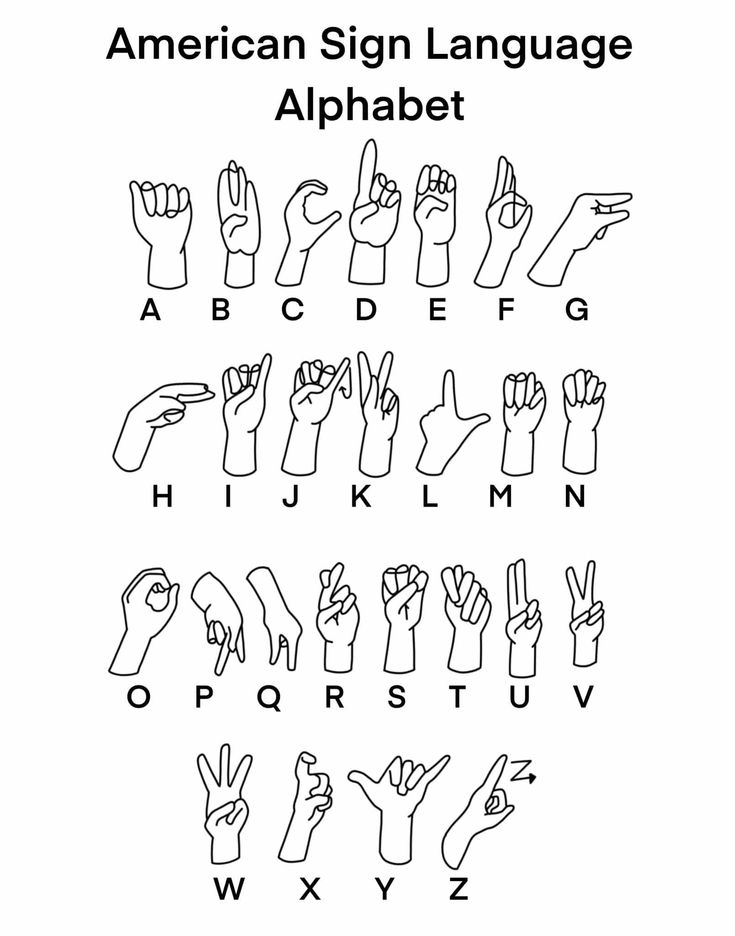

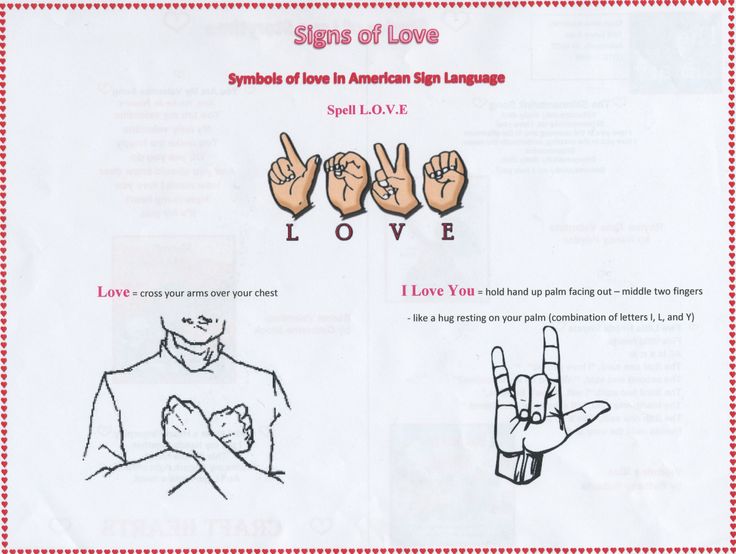

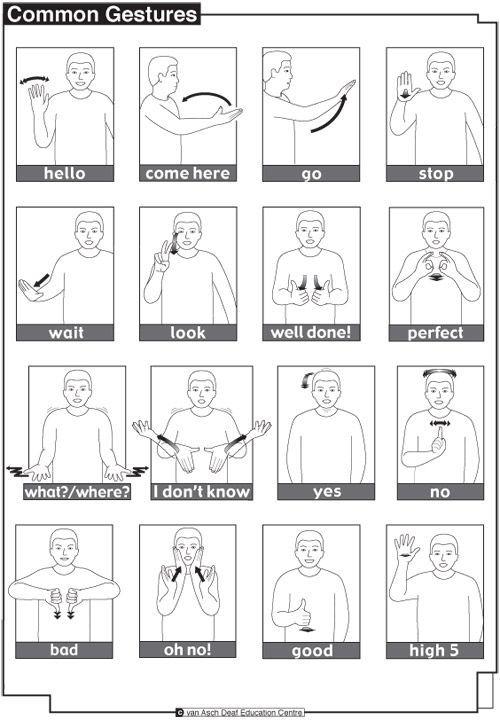

In parting, I asked Eh Ta to share a few ASL signs he thinks everyone should know. Without hesitation, he signed “I love you” followed by “awesome,” “Nice to meet you,” and “champ” or “champion,” which they often use when playing basketball.

Since 1994, Utah has recognized ASL and accorded it equal status with other linguistic systems in public and higher education institutions. For resources and to learn more about ASL, visit the National Association for the Deaf website at nad.org.

Jean Massieu School of the Deaf just celebrated its 20th anniversary last year and remains committed to fostering a fully accessible bilingual — ASL and English — education for students. Founded in 1999 and merging with Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind several years later, they share the mission of best supporting the needs of deaf/hard of hearing students throughout Utah. For more history and information, visit usdb.org.

For more history and information, visit usdb.org.

How Sign Language Evolves as Our World Does

Scroll

For more than a century, the telephone has helped shape how people communicate. But it had a less profound impact on American Sign Language, which relies on both hand movements and facial expressions to convey meaning.

Until, that is, phones started to come with video screens.

Over the past decade or so, smartphones and social media have allowed ASL users to connect with one another as never before. Face-to-face interaction, once a prerequisite for most sign language conversations, is no longer required.

Video has also given users the opportunity to teach more people the language — there are thriving ASL communities on YouTube and TikTok — and the ability to quickly invent and spread new signs, to reflect either the demands of the technology or new ways of thinking.

“These innovations are popping up far more frequently than they were before,” said Emily Shaw, who studies the evolution of ASL at Gallaudet University in Washington, D. C., the leading college for the deaf in America.

C., the leading college for the deaf in America.

The pace of innovation, while thrilling for some, has also begun to drive a wedge between generations of Deaf culture.

Perhaps the most dramatic example: To accommodate the tight space of video screens, signs are shrinking.

“My two daughters sign in such a small space, and I’m like, can you please stretch it out a little?” said E. Lynn Jacobowitz, 69, a former president of the American Sign Language Teachers Association. “We chat on FaceTime sometimes, and their hands are so crunched up to fit on the tiny phone screen, and I’m like, ‘What are you saying?’”

The problem is familiar to Dr. Shaw, 44, and her wife, who is Deaf. (Just as there can be different signs for the same thing, Deaf is capitalized by some people in references to a distinct cultural identity.) They have four children, ranging in age from 7 to 19, who often use the language differently — signing with one hand, for instance, for words that she and her wife might typically make with both.

“When they’re talking with each other, and with their peers,” she said, “I have a very hard time following the conversation.”

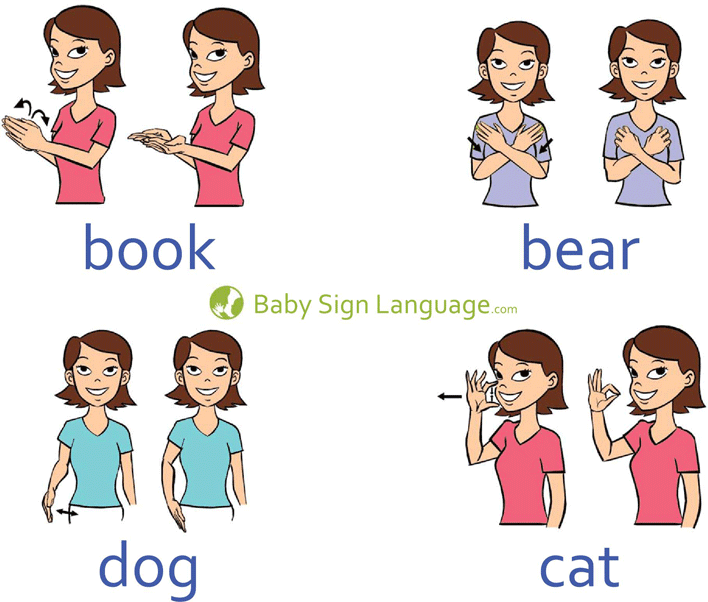

This is one well-known older sign for “dog,” which evokes the act of calling a pet to your side. It takes up more space and isn’t easy to see on small screens.

A newer, tighter version of the sign is based on the finger spelling of the word. The letters “D” and “G” are repeated twice, making the sign also look like a person snapping for a dog’s attention.

Even the oldest signs in ASL are still relatively young, by language standards.

American Sign Language was heavily influenced by French Sign Language, but it wasn’t standardized or formalized until the American School for the Deaf was founded in 1817. The number of people who use it is difficult to quantify (ASL isn’t an option on Census forms), but in 2006, researchers estimated that it was probably around 500,000.

From the beginning, signs that were more complex or crossed more zones of the body have tended to fall out of favor, experts said. But small screens appear to be accelerating that trend, both by encouraging tighter gestures and giving the new versions a way to spread quickly — just like a new dance move on TikTok.

“If a person sees someone they like on social media using a new sign, they might think it’s better and adopt it,” said Ted Supalla, a Deaf linguist who has researched the evolution of sign languages. “That’s a challenge for the community, because it’s a different kind of language transmission.”

Unlike spoken languages, American Sign Language is not typically passed down through generations of a family. More than 90 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, so they have tended to learn from institutions or their peers rather than parents.

That creates a higher degree of variation between different generations of deaf people than is typical with spoken languages, said Julie A. Hochgesang, a Deaf linguist at Gallaudet University who maintains an ASL sign bank that documents variations in ASL.

Hochgesang, a Deaf linguist at Gallaudet University who maintains an ASL sign bank that documents variations in ASL.

For a portion of the 20th century, many schools for the deaf were more inclined to try to teach their students spoken English, rather than ASL, based on harmful beliefs that signing was inferior to spoken language.

Today, with ASL on the upswing, young people might be learning it from Chrissy Marshall, 22, a deaf TikTok influencer living in the Los Angeles area. ASL has its own rules of grammar, but in her videos, she sometimes adapts her signs to more closely follow the English rules that her viewers might know better.

Those kinds of changes don’t sit well with everyone. MJ Bienvenu, 69, of Austin, Texas, quit an 87,000-member ASL Facebook group because she said too many people were using newly invented signs that didn’t fit the language’s existing guidelines.

“Many people were inventing signs that didn’t make sense,” said Dr. Bienvenu, who is a retired Deaf studies professor. “I feel like many people don’t realize that they bastardize ASL, and it harms more than it helps.”

“I feel like many people don’t realize that they bastardize ASL, and it harms more than it helps.”

The sign that April Jackson-Woodard’s grandfather uses for “ice cream” looks a little like someone scooping soup from a bowl. It’s a sign that has been used in Black American Sign Language.

But most of the time, Ms. Jackson-Woodard and her family (including her daughter) sign “ice cream” as if they are licking it off a cone, which is the common sign in ASL.

Black American Sign Language developed separately from ASL because of segregation in deaf schools. Its evolution has been studied less than that of ASL, and the two can differ considerably, with variations based on regional and cultural norms.

BASL scholars say it is more similar to early American Sign Language than it is to the latest iteration. For example, BASL users tend to use more two-handed signs and a larger space.

Ms. Jackson-Woodard, 37, is a Deaf interpreter living in the Washington, D. C., area. She can observe some of the differences between ASL and forms of BASL in her own family, which includes multiple Deaf generations.

C., area. She can observe some of the differences between ASL and forms of BASL in her own family, which includes multiple Deaf generations.

“He signs ‘ice cream’ the way he does,” she said of her grandfather, “because back then, he couldn’t afford a cone, so he ate ice cream in a bowl. He’d combine ice cream and milk in a bowl to make creamy ice cream.”

Ms. Jackson-Woodard switches among different BASL signs depending on whether she is chatting with her grandfather, her parents or her children, and does the same in ASL or BASL, depending on the audience she is interpreting for.

“I think it’s important to keep the old signs,” she said, “because maybe one day you’ll use it again.”

The traditional sign for “parents” involves placing a hand at the head for “father,” then placing a hand at the chin for “mother.”

One newer version of “parents” is done in the middle of the face, in an attempt to avoid gendered signs for parents who are nonbinary.

Though some people hold onto the older signs, a growing number of younger ASL users are adopting new ones that reflect shifting cultural norms.

Traditionally, signs relating to women, such as “wife” and “mother,” involved touching the lower half of the face, based on bonnets that girls once wore. Signs relating to men, like “husband” or “father,” were on the upper half of the face, emblematic of tipping one’s hat.

Many L.G.B.T.Q. people who are deaf have used a gender-neutral sign for parents for years, alongside versions of the word “parent” that involve signing “mom” or “dad” twice. Leslye Kang, 30, of Washington, said that when he sees someone incorrectly using the old sign for parents, he’ll speak up.

“If the word is not culturally appropriate, I’ll correct the sign,” said Mr. Kang, a graduate student and assistant basketball coach at Gallaudet. “With other older signs, I’ll leave people alone because I respect their heritage and recognize that their signs have been passed down through generations. ”

”

Many signs are metaphorical, linking visual objects or gestures to concepts. So when cultural shifts change the very concept of a word, a sign may no longer make sense.

One example, according to linguists like Dr. Shaw, is the word “privilege,” which is increasingly used in discussions about which groups have more social advantage, such as white privilege or male privilege.

One older sign for “privilege” could also mean “benefit,” “gain,” “credit” or “profit.” It looks like putting a dollar into a shirt pocket.

A newer sign visually represents someone being raised up, or put ahead, and is reminiscent of the ASL sign for “inequality.”

While that particular older sign for “privilege” worked well when expressing wealth advantages, it doesn’t fit as well when discussing social privilege, said Benjamin Bahan, an ASL and Deaf studies professor at Gallaudet.

“You want to really emphasize the point that when someone has ‘privilege,’ they’re in a position where they have more rights and more access to things in an unequal way,” he said of the newer sign.

Although the differences can sometimes lead to tension, ASL linguists emphasize that there is no right or wrong choice for a sign — because language is shaped by those who use it.

The longer and more widely a sign is used, the more standardized it becomes, and ASL is still a fairly young, dynamic language that has overcome decades of stigma. The best way to figure out which words to use, Dr. Hochgesang said, is to connect with deaf communities.

“Signs themselves are nothing without the people using them,” she said.

April Jackson-Woodard, Julie Hochgesang, Leslye Kang, Ted Supalla, Hannah Shaw, Akeisha Jackson and Kisha Hopwood

The videos for this article were filmed in Washington, D.C. Several of the subjects are associated with Gallaudet University, home to many prominent ASL scholars. Robert Weinstock, a spokesman, provided assistance.

Art direction, design and development by Eden Weingart. Produced by Heather Casey.

Basketball rules: gestures of judges in basketball

Hello, dear visitors of the site " Basketball Lessons ". Today we will talk about one of the integral parts of the refereeing process in a basketball game - the gestures of the referees. Basketball referees gestures serve to explain to both the spectators and table officials what point of the basketball rules was violated, by whom it was violated and what sanctions the player who violated the rules will incur.

Today we will talk about one of the integral parts of the refereeing process in a basketball game - the gestures of the referees. Basketball referees gestures serve to explain to both the spectators and table officials what point of the basketball rules was violated, by whom it was violated and what sanctions the player who violated the rules will incur.

This article was written using FIBA official rules of 2010, which are currently the basis for all professional basketball tournaments in territory under the control of the International Federation of Basketball Associations. To quote these rules: “The signs given in these Rules are the only official signs. They must be used by all referees in all games. It is important that table officials are also familiar with these gestures.”

We will begin the story about the gestures of basketball referees with the gestures that indicate shots on the ring , successful throw attempts, as well as an indication of the number of points scored.

Rules of Basketball: referee gestures - throwing the ring

The next series of referee gestures affects everything that is somehow connected with playing time. Basketball Rules: Basketball referee gestures about playing time

Administrative gestures of basketball referees are related to substituting one player for another, inviting a player to the court, announcing a timeout, as well as visual demonstration of the countdown (five seconds and eight seconds) . In addition, there is a gesture that is used to communicate between referees and table officials. Basketball rules: administrative gestures of referees

The next group of gestures, which includes eleven types of gestures, is designed to demonstrate to the spectators and table officials which rules of basketball were violated in this particular episode. Referee signal will tell us if the player had a run or used an incorrect dribble (double dribble, carry), if the player was too long in the three-second zone or did not have time to put the ball into play, if the kick was intentional or if the player fouled a rule zones. Basketball rules: gestures of basketball referees violation of the rules

Basketball rules: gestures of basketball referees violation of the rules

Okay, the player violated basketball rules (committed a foul) and the referee noticed it. Now he must fully inform the referee's table about this. The whole procedure consists of three steps. The first step is to notify the table officials of the number of the offending player. Rules of Basketball: Referee Informing Gesture

The second step is to demonstrate what type of foul has occurred: misuse of the hands, collision with a player in possession of the ball or a player without the ball. Also, in certain situations, the referee may call a double foul, technical foul, unsportsmanlike foul or even a disqualifying foul.

Rules of Basketball: Foul Type Gesture

Finally, the referee's third step is to announce the number of free throws awarded (one, two or three shots). If the violation of the rules does not involve free throws, then the referee must indicate the direction for the continuation of the game. Rules of Basketball: Punishment for Violations of the Rules Rules of Basketball: Punishment for Violations of the Rules

Rules of Basketball: Punishment for Violations of the Rules Rules of Basketball: Punishment for Violations of the Rules

So, the referee has already shown the type and type of violation of the rules and determined the punishment for him. The last group of gestures of basketball referees refers directly to the performance of free throws (free throws). Moreover, the type of gesture differs depending on whether the referee is inside the restricted area or outside it. Rules of Basketball: Free Throws Rules of Basketball: Free Throws

This is the end of the article devoted to such important elements of basketball as referees' gestures. Thanks to it, without the help of a commentator (especially in English-language broadcasts), we will be able to figure out who and for what violation of the rules of the game of basketball was assigned a personal note; we will see how the referee, who is on the site, addresses his colleagues, who are at the referee's table, with gestures. Now - the body language of arbitrators can become an open book for us.

Now - the body language of arbitrators can become an open book for us.

By the way, on the subject of gestures of basketball referees - one very funny video.

[youtube]9dSMG1FTSjg[/youtube]

Good luck with your training and see you soon on the pages of this site!

Online Dictionary of Sign Language. Three projects of an engineer for people with hearing impairments

Communication with Alexei Prikhodko, an engineer and junior researcher at Novosibirsk State Technical University (NSTU NETI), we decide to arrange via Skype: this is the case when I had to go online not only because of self-isolation, but also because of being busy.

Prikhodko is working on several projects at once, all of which are somehow related to Russian Sign Language: a program for recognizing and translating sign language into written language, a program for recognizing Indian sign language, a very important educational project for deaf children "Mathematics in Silence" for Alexei - online - a platform that will help schoolchildren prepare for the exam in mathematics.

How difficult it is for a deaf person to learn, Alexey was convinced from his own experience. That is why almost all of his projects are for people with reduced or absent hearing. Prikhodko is sure that the more active use of sign language in the educational process greatly facilitates the perception of information.

Speaking through an interpreter about his scientific work and love for volleyball, he suddenly turns his back on me and shows the inscription on his sweatshirt — a memorable gift received at the Digital Breakthrough competition, after which the ANO "Russia — the Land of Opportunities" invited Prikhodko to meeting of the Supervisory Board of the platform to speak to Putin.

In the third generation

Alexey was born in the village of Khatanga near Norilsk. His hearing is absent already in the third generation, and maybe even in the fourth or fifth, says Alexei. At the same time, on the mother's side, the relatives were deaf, on the father's side - all hearing.

"Grandfather on my father's side was hearing, he worked as a school director, was a teacher of mathematics, maybe that's why I became interested in mathematics," says Prikhodko.

© NSTU Press Service

The boy felt problems with communication at a very early age.

"I went to kindergarten with hearing children. It turns out that there was no development and upbringing, I just played, I was alone," he says.

Then the boy was enrolled in a specialized kindergarten, and after that his mother decided to send her son to the Achinsk school for the hearing impaired. There, in high school, he became so interested in volleyball that he even began to think about a career as a professional athlete.

"I started playing sports at the age of 16. In the 10th grade, a new volleyball teacher came, he got us very interested. We started performing at competitions, competed with hearing people. The team of our school participated in tournaments in the city of Achinsk and throughout the region , we won prizes," he recalls.

They practiced so seriously that Prikhodko passed the rank of master of sports in volleyball. Mathematics also went well: in this subject, he consistently received good grades and won Olympiads.

But the rest of the subjects were not easy. Difficulties in learning, Alexei recalls, were caused by the fact that teachers practically did not use sign language.

"They communicated with the children using oral speech, this is due to the training program. In the family, I constantly communicated with parents, brothers and sisters in Russian sign language, so communication with teachers at school was difficult," he shares.

Science won

After school, Alexei was invited to Novosibirsk: he participated in the Olympiad organized by the Institute of Social Rehabilitation of the Novosibirsk State Technical University and proved himself well.

"I had a choice - either go into sports, play volleyball seriously, or go to NSTU. I liked sports more, but everyone insisted that I go to NSTU," Prikhodko shares.

First, the young man entered the college level at the Institute of Social Rehabilitation of the Novosibirsk State Technical University with a degree in computer science. At that time, he had not only no idea about the profession of a programmer, but even a computer.

"The financial situation of my parents did not allow me to buy it at that time. I did not understand at all what a computer is, why it is needed," recalls Alexey.

Since profile subjects started only in the third year, at first it was not a big problem, and then grandfather came to the rescue, with whose savings they bought such an important thing for a programmer. Prikhodko mastered computer programs quickly and defended his diploma with excellent marks.

Then there were four years of bachelor's degree and a lot of training.

"I participated in the Deaflympics in 2009 in Taipei, became the winner of the Russian beach volleyball championships," says the source.

Mathematics and volleyball continued their confrontation. Prikhodko began to implement his first projects already in the bachelor's degree, but since he paid more attention to sports, he could not get into the budget for the master's program. I had to change the department at the same faculty - automation and computer technology, where Alexei easily passed on the budget.

Prikhodko began to implement his first projects already in the bachelor's degree, but since he paid more attention to sports, he could not get into the budget for the master's program. I had to change the department at the same faculty - automation and computer technology, where Alexei easily passed on the budget.

However, problems again awaited him: the teachers of the new department, unlike the previous one, had no experience in teaching for the deaf, and before enrolling, Alexey decided not to tell anyone about his peculiarity. Despite this, he coped with the program in the general group: some issues had to be resolved with an interpreter, classmates helped somewhere.

While studying for a master's degree, Alexey took part in the competition of the Vladimir Potanin Charitable Foundation, where he won a grant, being among the top 300 undergraduates in Russia according to the foundation's rating. After that he successfully entered graduate school and graduated from it.

As for volleyball, now Alexey devotes much less time to it, but even today he plays for the university and the faculty. And being in self-isolation, he replaced the sport with running through the forest.

Gesture polyglot

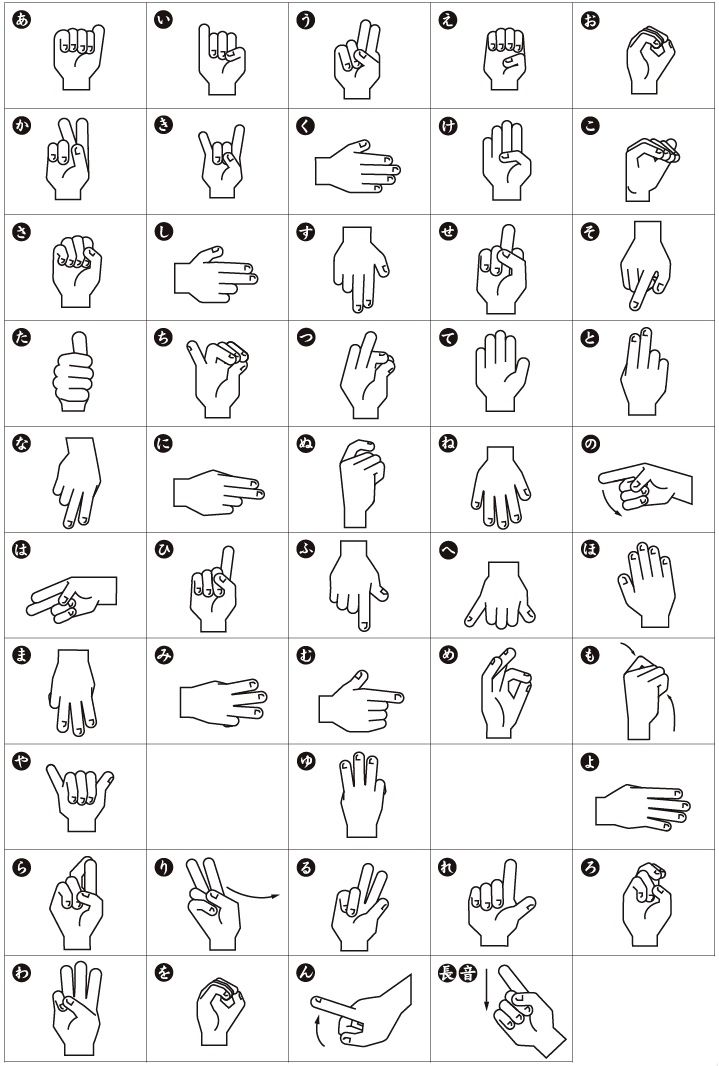

Now Alexei can communicate in four sign languages - German, American, Russian, he has also mastered communication using the international sign system, which allows him to discuss simple topics.

After graduate school, the young man lived in Germany for six months on an exchange program, worked at the University of Hamburg, one of the largest academic centers in Germany. It is this experience, Alexey believes, that became one of the most important for his further scientific work.

© NSTU Press Service

"I heard that in Germany there is a study of sign languages, that there is a written system of notations - something that we have not developed in Russian sign language. There are a lot of technologies in German sign language, which are suitable for programming, this is called sign language notation," says Prikhodko.

A Novosibirsk programmer got to the University of Hamburg by correspondence - his knowledge of written English, which he constantly improves, helps him communicate with European IT specialists and foreign colleagues.

"The university has a department called the Institute for German Sign Language Research. Just what I need for my computer research. German Sign Language is different, we had a hard time communicating at first. But, fortunately, they found me a translator who translated from German sign to Russian sign. For six months I worked in Germany at the University of Hamburg," says Prikhodko.

During this period, Alexey managed to go to Munich to attend a prestigious international conference for deaf IT specialists, where a large number of contacts were made, and Alexey was even offered a job. But Prikhodko decided to return to his homeland.

Meeting with Putin and a black Mercedes

"I took part in the all-Russian competition of programmers "Digital Breakthrough", did not get into the number of winners, but I managed to get first to the semi-finals, and then to the final. One of the main organizers of the "Digital Breakthrough" breakthrough" invited me to a meeting with President Putin," says Alexey.

One of the main organizers of the "Digital Breakthrough" breakthrough" invited me to a meeting with President Putin," says Alexey.

The meeting took place at the final project session of the "Russia - Land of Opportunities" project in Sochi.

"I was surprised because I did not submit any applications, but they told me: you just come and find out everything. I had an inner feeling that there would be a very important meeting, but I did not expect that this meeting would be with the president ", Alexey recalls.

At events, Alexei usually performs in his usual clothes: sweatshirt or sweater, jeans.

"But this time, again, some inner feeling told me that the event was important. For the first time in my life, I took a suit with me and was not mistaken. At the airport, I was met in a huge black Mercedes," says Prikhodko.

Aleksey Prikhodko (4th from left) taking pictures with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Sochi, 2019

© Mikhail Klimentyev/Press Service of the President of the Russian Federation/TASS

" in Sochi. Here, young scientists were selected from all the participants, who had to tell Vladimir Putin about their projects. Alexey Prikhodko was one of them.

Here, young scientists were selected from all the participants, who had to tell Vladimir Putin about their projects. Alexey Prikhodko was one of them.

About projects

Now Prikhodko has three projects. One is related to Indian sign recognition, in this project, which supported The Russian Foundation for Basic Research, he is the executor, works under the scientific supervision of Professor NSTU NETI Mikhail Grif.

Work is also underway on a project to recognize and translate sign Russian into written language. Here Alexei also has support - a presidential grant.

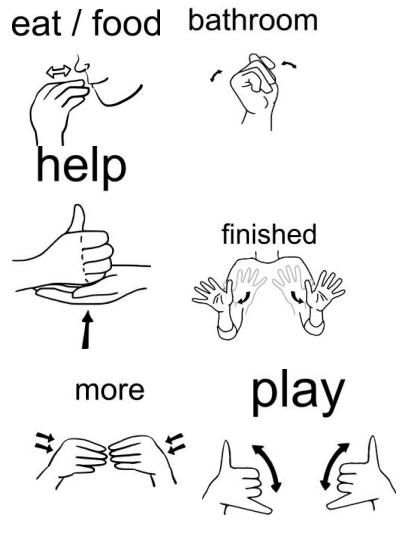

Thanks to the system being developed, it will become much easier for deaf people to communicate - now the program can recognize individual gestures and translate them into written language. You can work on a computer without using a mouse - adjust the brightness, volume, control the cursor.

A webcam is sufficient to test the system, but a mobile phone camera will also work. "The person in front of the webcam shows individual gestures. This video stream is sent to the server, and algorithms for recognizing individual elements of the gesture work there - face, hands, fingers. The beginning of the gesture, the end of the gesture are determined. The presented gestures are compared with the base of gestures. In case of significant similarity on A written interpretation of the gesture appears on the screen," Prikhodko explains.

"The person in front of the webcam shows individual gestures. This video stream is sent to the server, and algorithms for recognizing individual elements of the gesture work there - face, hands, fingers. The beginning of the gesture, the end of the gesture are determined. The presented gestures are compared with the base of gestures. In case of significant similarity on A written interpretation of the gesture appears on the screen," Prikhodko explains.

As long as the system focuses on recognizing individual gestures rather than sign language, this will be the next step. Now Aleksey is conducting a phonological analysis of Russian Sign Language (RSL), collecting videos in RSL from a video dictionary, and creating a phonological dataset (labeled datasets) of RSL for machine learning.

"My goal in the project from the Presidential Grants Fund is to create an online dictionary from Russian Sign Language into Russian and other functions to support RSL. There are many dictionaries from Russian into RSL, but there is no reverse translation," Prikhodko explains.

In the future, Alexey plans to return to the project to prepare deaf students for the Unified State Examination.

"The project has been suspended for the time being, but the site itself, the online platform is available. Schoolchildren are now working on it, we have been working on this project for a year with a team of volunteers as part of a grant, together with my colleague Dmitry Kruchinin from Tomsk. I plan to continue this project, this is there may be other school subjects - physics, chemistry," he says.

© NSTU Press Service

Educational projects are especially important for Alexey.

"I have studied in a school for the deaf all my life, I remember the not very high quality education that we had, and I understand how difficult it is for deaf children to study. The fact is that there are defectologists who deal with deaf children only with oral speech and do not use sign language. The small amount of use of sign language in the educational process, in my opinion, makes it difficult to master knowledge.