Home »

Misc »

How to stop a fastbreak in basketball

How to stop a fastbreak in basketball

Defensive Transition – How to Stop the Fast Break

As a Speed Game type Coach, I was always interested in how other coaches attempted to slow my teams down. And long before I really understood how to run an effective Speed Game, I was concerned about not having my teams get run off the court by quicker opponents. Early in my career I learned that my two guards needed to be responsible for getting back early and stopping our opponent’s running game. But I still faced the problem of trying to run with my slower, bigger teams vs shorter, quicker squads. Could we stay with them, or was it just going to be a losing battle?

I discussed this problem with various coaches and asked, “How do you stop the Opponent’s Fast Break?” Here are some of the comments I received concerning Defensive Transition:

- We have to shoot well from 3 to stop the opponent’s running game.

- We don’t go to the Offensive Boards because we have to get back to stop the opponent’s fast break.

![]()

- We have to play “slowdown” to stop the opponent’s offensive transition game.

I disagreed with all three of those conclusions and did just the opposite with all of my teams and survived. In the first case, while your guy is holding up three fingers to the crowd after making a “3”, we would take it out quickly and fill three lanes going the other way hard. So making a “3” didn’t slow us down much.

In the second case, I would never give up offensive rebounding to stop someone’s fast break. Two guards get back on the shot and the frontline 3 “always” hit the offensive boards, then sprint back on defense.

In the third case, we would never play “slowdown” because someone wants to run. We welcomed the pace and challenged you to run transition both directions better than we did. That’s my Transition Philosophy because I like coaching the Running Game.

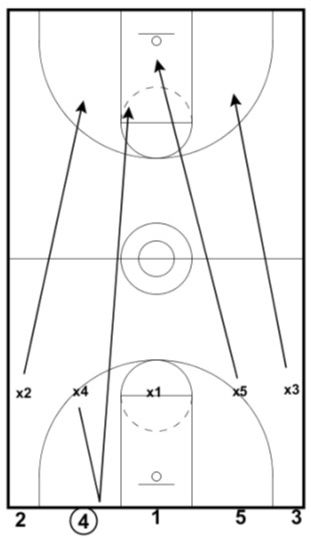

In my opinion, the best way to stop an opponent’s fast break (as I mentioned earlier) is to assign your guards to rotate back as soon as your team shoots. (Diagram #1) If one of your guards is driving to the basket and shoots, at least the other one will have “back” responsibility covered until help arrives. The driving shooter, if a guard, should get back as fast as he can after his inside shot attempt. The three frontline players will always crash the Offensive Boards (Diagram #1), but they too must get back into the defensive key as fast as they can when the opponent gets possession. (Diagram #2) So basically, on any change of possession, all five players must transition back into the key as quickly as they can. Anyone who does not get back immediately on Defensive Transition should be taken out of the game. They are evidently too tired to continue playing because Defensive Transition is an absolute must for all of my players. I want a running team and if someone is too tired to sprint back on defense, they obviously are too tired to run their lane hard on an offensive fast break.

(Diagram #1) If one of your guards is driving to the basket and shoots, at least the other one will have “back” responsibility covered until help arrives. The driving shooter, if a guard, should get back as fast as he can after his inside shot attempt. The three frontline players will always crash the Offensive Boards (Diagram #1), but they too must get back into the defensive key as fast as they can when the opponent gets possession. (Diagram #2) So basically, on any change of possession, all five players must transition back into the key as quickly as they can. Anyone who does not get back immediately on Defensive Transition should be taken out of the game. They are evidently too tired to continue playing because Defensive Transition is an absolute must for all of my players. I want a running team and if someone is too tired to sprint back on defense, they obviously are too tired to run their lane hard on an offensive fast break.

When a player feels he is getting too tired to continue running back on defense or running a fast break lane, he can signal for a sub and a short rest. With my teams, we used a sign of a closed fist over the heart. The player looks to the bench and catches the coach’s eye, then gives the sign. He is replaced at the next whistle and can return as soon as he feels he is recovered and ready to go hard again. If the action continues for several more possessions after a player has given the “tired sign,” we tell him to rest on the offensive break, but never on defensive transition. I’ve even gone so far as to tell the team that if they think they are going to pass out from exhaustion, just make it to the defensive end before doing so. That way the opponents have to at least step around your poor, defenseless body before they can score. Some players look at me with surprise and shock, but most know it is just my sense of humor kicking in to explain the importance of Defensive Transition.

The path to a good Transition Defense is to get all players back into the opponent’s key as quickly as possible. I teach my players to sprint to mid court, then look over their shoulder to locate the ball. This gives a picture of where a fast break attack is headed. Maybe there is none. The opponent may choose to slow it down and not push the pace. In that case, our defenders can cruise back to the key from mid court and locate their assigned man. But if a “push” is on and the opponent is “on the run,” our defenders need to continue sprinting hard into the key and plug up any potential drive down the middle. While retreating, our defenders also size up where their assigned man is in relation to the attacking end of the court. Is he on the left wing, right wing, low post, or trailing the action? We do not want to give up a layup, but we also want to find our assigned man eventually to prevent open outside shots.

The drills I use to train players on Defensive Transition are discussed in earlier Blog Posts. (O.D.O. – December 4, 2016 and Cycles – November 17, 2016) Please look those up if you want further information. Other things I do in practice to reinforce the importance of Defensive Transition include:

(O.D.O. – December 4, 2016 and Cycles – November 17, 2016) Please look those up if you want further information. Other things I do in practice to reinforce the importance of Defensive Transition include:

- Insist the “1” and “2” always rotate back even during half court 5 on 0 reviews.

- Watch to make sure all retreat hard on every change of possession during scrimmages or full court drills.

- Rewind (backup) a successful fast break to see where a defender let us down with less than his best effort. Then replay it correctly.

Good habits are established in practice every day with careful observation and correction by the coaching staff. The more you can practice good transition, the better your team will become with it. Never allow fatigue or laziness to cause your team to be “less than the best” on Defensive Transition.

Key Teaching Points:- Assign two players to get back on every shot attempt by your team.

2. Insist on quick Defensive Transition on every change of possession.

3. Sub out any player who does not get back immediately on defense.

4. Allow players to sub themselves out when tired, but return when rested.

5. Require frontline players hit the offensive boards, then get back quickly.

If you would like to read more on my thoughts about Offensive and Defensive Transition, you can check out my book You Can Run With Anyone. It’s available in ebook or paperback.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Defending the Basketball Fast Break

Stopping the fast break is a difficult but important part of the game and a key to being a good defensive basketball team.

Stopping the fast break is a difficult but important part of the game and a key to being a good defensive basketball team. Transition defense takes effort, anticipation and intelligence. Even then a well executed fast break is difficult to stop.

Transition defense takes effort, anticipation and intelligence. Even then a well executed fast break is difficult to stop.

The key to fast break defense is to first get immediate pressure on the ball and delay the attack. Do not just let the outlet man run out and begin a quick transition. Slow down the initial pass and force the ball out of the middle of the court. This will allow defenders to get back, fill lanes, and pick up their man. So make sure the closest man pressures the rebounder or outlet man on every possession. This single act will do the most to keep your opponent from getting out on a fast break.

If the initial pressure on the ball does not stop a fast break from developing, there are a number of other strategies to limit the damage and force your opponent into a half court set. The main thing once a fast break gets started is to hustle back on defense and get behind the ball. Fast breaks are about numbers and getting back quickly behind the ball will stop a fast break in its tracks.

We already mentioned forcing the ball wide and trying to keep it there once it is wide. This cuts the court space and limits passing options for the break. Get in front of the ball and try to make them pass back or pick up the dribble. In the meantime, defensive players are tracking back and getting in position.

Another strategy is to take a foul. If things are particularly dire and the game is tight, there is nothing wrong with taking a foul to stop the play. Be careful to not do so if you are over the foul limit as it will give the other team free throws. Otherwise, a well timed foul is a good strategy.

Also, try not to give away the free basket. Get up and challenge the shot. Maybe you'll get the block or at least pressure the shooter into missing. If not, make them earn the two points at the free throw line. Do not go soft on the foul though as you can find yourself giving up the three point play.

Stopping the fast break is difficult but using the ideas above can greatly slow down or stop a fast break most of the time. Take the time to discuss fast break defense as it is an important part of the game most basketball coaches do not put enough time into.

Take the time to discuss fast break defense as it is an important part of the game most basketball coaches do not put enough time into.

View Count: 14129

Stopping the fast break is a difficult but important part of the game and a key to being a good defensive basketball team.

Basketball Drills

Free Basketball Drills

Browse our fun and free youth basketball drills for kids to get ideas for your next basketball practice.

Browse Basketball Drills

Basketball Dribbling Drills

Basketball Passing Drills

Basketball Attacking Drills

Basketball Defense Drills

Basketball Fitness Drills

Basketball Layups Drills

Basketball Shooting Drills

Basketball Rebounding Drills

Basketball Drills by Age

Beginner Basketball Drills

Middle School / Jr High Basketball Drills

High School Basketball Drills

College Basketball Drills

Basketball Printable Resources

Basketball Score Sheet

Basketball Court Diagram

Fast Break Exercises | Basketball

The drills we have provided are designed to improve the basic skills of the fast break so that it can be used as a command offensive system.

The first exercise is the struggle for possession of the ball after an unsuccessful throw.

Exercise "ball" (Fig. 62). Two players stand on either side of the basket. The coach throws the ball into the basket, and the player who takes possession of the ball gives a voice signal: "Ball!" Assistants are positioned in the receiving areas of the first transmission at the sidelines. The player in possession of the ball on the backboard must quickly find an assistant and pass the ball to him, using a two-handed overhead pass, a hook or one hand from the shoulder. After the transfer, the players change places. First, the exercise is performed without resistance. The passes are then blocked by defenders.

Three against two (fig. 63). This is one of the most important exercises in learning to break fast. One of the coaches is located at the top of the free throw area on one side of the court, the other is on the other side at the touchline at the place of its imaginary intersection with the free throw line. Defenders 1 and 2 are located at the far end of the site. On the near side are two players participating in the fight for the ball on the backboard (No. 1 and 2), and player 3, who receives the first pass. The coach throws the ball into the basket, and the player in possession of the ball gives the signal: "Ball!" The player receiving the first pass goes to the touchline on the side of the ball. He always comes from behind the partner with the ball to this position so that the partner sees him and does not perform a blind pass, to the voice.

Defenders 1 and 2 are located at the far end of the site. On the near side are two players participating in the fight for the ball on the backboard (No. 1 and 2), and player 3, who receives the first pass. The coach throws the ball into the basket, and the player in possession of the ball gives the signal: "Ball!" The player receiving the first pass goes to the touchline on the side of the ball. He always comes from behind the partner with the ball to this position so that the partner sees him and does not perform a blind pass, to the voice.

Player 3, the middle player in the fast break formation, dribbles towards the center circle while players 1 and 2 move around the edges to the right and left of it. The dribbler uses high dribble until he encounters resistance. From time to time defender 1 must make a dash towards dribbler 3. As player 3 approaches the top of the free throw area, he must be very careful with the ball. He needs to distract defenders 1 and 2 so that he can pass to partners 1 or 2, which allows him to complete the attack with a shot to the basket on the move.

Three forwards and two defenders start the drill. After the players have mastered the interactions, the coach adds a third defender. The attackers must immediately orient themselves, and the middle player, without waiting for the help to come, plays the situation two against two or three against three. He passes the ball to the partner on the edge and screens him for a shot, or, passing the ball to one edge, screens the player on the other edge.

The third defender enters the game before player 3 gets close to the top of the free throw area to give the attackers time to assess the situation. It should be noted that it is much easier to create conditions for a throw in a three-against-three situation than, after waiting for help, to outplay an organized defense in a five-against five situation.

The coach on the attacking side occasionally adds a fourth accompanying player, calling him from the group of players standing under the basket or at the touchline. Since the middle player cannot see the follower, the follower must warn him with his voice so that the middle player can tie up the defenders and allow the follower to shoot for the basket.

This exercise will tell the coach which player intuitively knows how to pull a defender towards him to open the way for a follower, pass the ball to the edge if the dribble has already been used, or make another pass. From time to time, all back row players should be in the role of a middle player.

Fast break during free throws (fig. 64). When the opponent shoots free throws, the best player in the ball challenge under the backboard (No. 1) stands to the right of the basket. The second tall player (No. 2) takes place to the left of the basket. Player 3, the middle player in the fast break, is positioned near the intersection of the center and side lines, opposite player 1. The best hitter (4) is deep in the corner on the side of the middle player, and the second hitter (#5) is in the center of the court.

The purpose of the exercise is to beat the player of the opposite team who is taking a free throw (No. 3) and create conditions for player 4 to perform a jump shot. Once he has the ball, he can take any shot from 4m away.

Once he has the ball, he can take any shot from 4m away.

About 70% of free throws are successful. Therefore, the first thing that the exercise should teach is the speed of the thrower. He must grab the ball, jump over the end line and pass to player 3 without losing sight of defender 4. If the defender moves towards player 3, the thrower must pass the ball to player 5 towards the center line. (On a miss, player 1 takes possession of the ball, turns outward and immediately passes the ball to partner 5). Player 5 looks at partner 4, who is moving across the court, and passes the ball to him if it is open. If player 4 fails to open up, his partner can take on the role of the middle player. True, most often the ball is passed to player 3.

We believe that this drill teaches all the basic skills of the fast break attack. Therefore, we first teach only the form of interactions, then we turn on the passive defense, and finally we force the defenders to act aggressively in an attempt to stop the attack with a fast break.

Three against two in both directions (Fig. 65). The drill includes almost all the necessary interaction skills that are performed at high speed, and we believe that a team, especially if they want to incorporate a fast break into their offense, should use it in training as soon as the players can learn it. 16 players are located in six places around the court: two columns behind the end line and to the right of these columns at the touch line. Player 1 has the ball, player 7 to his right and player 4 to his left are ready to develop an attack in a situation of three attackers against two defenders Players 12 and 14. defenders, line up in tandem one after the other in the free throw area at the far end of the court. Player 1 starts the drill with a pass to player 7. Player 7 dribbles into the middle while players 1 and 4 break through the edges. On approaching the free throw area, player 7 attempts to shoot a pass to players 1 or 4. Only one shot is taken each time in the drill.

Player 1 and both of his partners do not pick up the ball on the rebound. Players 12 and 14 play defense, trying to block the shot. If the throw is nevertheless taken, player 12 takes possession of the ball and immediately passes it to player 10 at the right touchline. The latter begins to play the role of an average player with a fast break. If he sees that the ball bounces to player 14 on the other side, he must go across the court and signal with his voice that he is ready to receive the first pass from player 14. Player 10 moves with the ball in the center, and partners 12 and 14 break through the edges. Players 2 and 5 go into defensive positions at the far end of the court. The attack develops in the other direction.

This is a very good continuous drill that includes all the basic elements of a 3v2 fast break situation. The optimal time for its implementation is from 7 to 10 minutes. Periodically included in training during the preparatory and main periods of the training process, the exercise increases the endurance of the players.

It is desirable that the players occasionally change starting positions so that the middle player can play defense and other players are convinced of the importance of using the most technical player in the center of attack.

Fast break exercise with resistance (fig. 66). Starts at the far end of the site. The coach stands in a circle around the free throw. Players 1 and 2 play under the shield, while player 3 is on top of the defensive triangle. The coach takes the throw. One of the players (No. 1 or 2) takes possession of the ball on the bounce, turns outward and looks for partner 3, who must get into position to receive the first pass. Having received the ball, player 3 quickly leads it to the center, while players 1 and 2 break through the edges. Players 4 and 5 play defense at the far end of the court. Only one throw is allowed per exercise. Players 4 and 5 take possession of the ball on the bounce. Player 6, who is located on the right side of the sideline, goes to the center circle and takes up a defensive position. Players 4 and 5 try to beat Player 6 in a two-on-one fast break situation. After the throw, players 6, 4 and 5 stop and pass the ball to the coach. Player 4 and 5 stay under the shield, while player 6 goes to the top of the defensive triangle as a future middle player on the fast break. Players 9and 12 take defensive positions at the far end of the court. The coach starts the exercise again with a basket throw.

Players 4 and 5 try to beat Player 6 in a two-on-one fast break situation. After the throw, players 6, 4 and 5 stop and pass the ball to the coach. Player 4 and 5 stay under the shield, while player 6 goes to the top of the defensive triangle as a future middle player on the fast break. Players 9and 12 take defensive positions at the far end of the court. The coach starts the exercise again with a basket throw.

This is another useful continuous drill as it allows tall players to practice a two-on-one fast break situation.

Fast Break Combinations

The fast break is undeniably the most advanced, highest scoring offensive system in basketball. For a team using a fast break system, it does not matter whether the opponent uses a personal, zone or mixed defense system, whether he often changes defense systems during the match.

Once in possession of the ball, the team should always try to set up a fast break attack. But how can such an idea be put into practice? First of all, it is necessary that for various situations that arise after catching the ball, the further actions of the players are planned in advance.

But how can such an idea be put into practice? First of all, it is necessary that for various situations that arise after catching the ball, the further actions of the players are planned in advance.

There are various options for making a fast break. It is clear that it is impossible to train the team in all options. It is better to have fewer options in service, but to master them perfectly.

Some young coaches try to teach players everything they know right away. But most players (especially those who are not experienced enough) cannot digest the whole mass of this knowledge, and the expected result does not work. It will be better if, during the training process, the coach offers the team a simpler and more effective option for a quick break, based on the physical characteristics and technical capabilities of their players.

The situation is different with various methods (methods) of organizing a quick breakthrough. There are many such methods, but, unfortunately, our basketball literature recognizes only one technique - passing the ball. This complicates the actions of the players, limits the possibility of using a fast break.

This complicates the actions of the players, limits the possibility of using a fast break.

More than that. Coaches sometimes do not allow their players, even under the right conditions, to use any other technique to organize a fast break other than passing. But we have no right to say that the transfer is the only way to a quick breakthrough. To think so is to mark time.

It is expedient, for example, after catching the ball that has bounced off the backboard, in some situations it is advisable to use dribbling. This allows you to go through the opponent's defense, achieve numerical superiority, create a convenient position for passing the ball to a partner and further actions.

Some might say that the team, using the dribble, will be late in organizing a fast break. However, practice shows that this is not the case.

In the old days, when the ball bounced off the backboard, as a rule, only the center forward and defender fought for it, it would simply be pointless to use the dribble to organize a fast break. After all, the enemy players, after an unsuccessful throw, quickly returned to their shield to organize defense.

After all, the enemy players, after an unsuccessful throw, quickly returned to their shield to organize defense.

The situation is different now, when six, and sometimes more players are fighting for a bounced ball under the basket. It is enough for a player who has mastered the ball at his backboard to break out of a bunch of opponents and partners, and with the help of a dribbling he can create a numerical advantage for a successful fast break.

Everyone knows what often happens when a defender in the attacking zone tries to keep the attacker in possession of the ball at a very close distance. The latter, with the help of dribbling, easily bypasses the defender and throws the ball into the basket.

But the same close distance happens between the attacker and the defender after catching the ball that bounced off the backboard. Why, then, in the first case, in the attack zone, the attacker can achieve his goal with the help of dribbling, while in the second case, no less convenient, this is not allowed? The absurdity of such a situation is obvious.

* * *

So, when is the best time to make a fast break? After playing jump balls, after a free throw, when throwing the ball in from behind the end and side lines in the defensive zone, and mainly after taking possession of the ball that bounced off its backboard.

The fight for the ball bouncing off the shield is of paramount importance. After all, mastering the ball gives the team the opportunity to attack!

If the players of the defending team act correctly, they will almost always be able to take possession of the ball after it has bounced off the backboard. How can this be achieved?

First of all, when the opponent attacks the basket, the defenders must have time to position themselves between the attackers and their backboard. After the throw, each defender vigilantly monitors the actions of his ward. If the attacker rushes to the basket to take possession of the bounced ball, the defender, turning his back to the opponent, blocks his way to the shield with his body. Unfortunately, defenders often forget to do this and after a shot on the basket leave their players without supervision, while they themselves reach for the backboard to take possession of the ball.

Unfortunately, defenders often forget to do this and after a shot on the basket leave their players without supervision, while they themselves reach for the backboard to take possession of the ball.

This is a gross mistake! The ball can bounce towards an attacker who is not covered by a defender. It is clear that this attacker will catch the ball without interference and retake the throw. In addition, in such cases, the attacker, without encountering resistance, can take the shortest route to the best place to catch the rebounded ball.

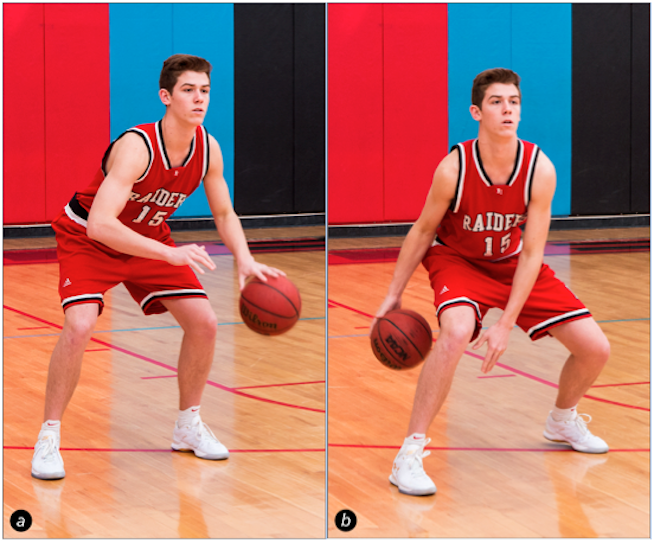

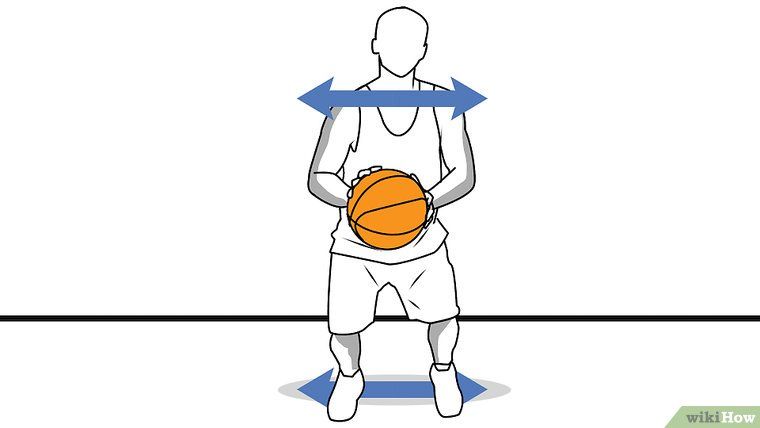

After the defender turns to cover the attacker, he must move forward a little to avoid a collision with an opponent and not foul (this does not apply to a defender who guards a center forward playing near the basket). Further, bending his knees, the defender places them shoulder-width apart. In order to occupy more space and more accurately guess which side the opponent wants to pass from, the defender should spread his arms bent at the elbows wide, lowering his forearms down. Some foreign trainers advise lifting the forearms up. But this is not rational. Indeed, if the defender makes a jump later on, he, by sharply raising his forearms, will be able to jump higher.

Some foreign trainers advise lifting the forearms up. But this is not rational. Indeed, if the defender makes a jump later on, he, by sharply raising his forearms, will be able to jump higher.

What if the attacker is under the shield next to the defender? It is necessary that the defender is in front of the opponent, so that his leg is also in front of the attacker's legs. This situation is clearly seen in the picture that captured the moment of the meeting between the USSR and the USA in Moscow. The defender's arm, bent at the elbow, is above the opponent's arm. This is a very important detail! This position of the hand will prevent the attacker from making a well-timed jump.

What to do if the ball bounced towards the opponent? It is recommended to quickly take a step in the direction where the ball can land, raise your hands and try to cover the opponent's hand with your hand. Now you need to catch the ball!

The player who catches the ball must be able to instantly understand the situation - to know which side his closest opponent is on and which side is free. This will make it easier for the player to move forward with a fast break.

This will make it easier for the player to move forward with a fast break.

Catching a rebounded ball in a jump, the defender is still in the air, before landing, quickly turns his head in the direction where there is no opponent. At the same time, the player turns his back to the nearest opponent and spreads his legs wide before landing.

What gives a clear performance of this technique? The opponent loses the opportunity to take the ball when the player in possession of it lands, and this latter immediately finds himself facing the direction of the opponent's backboard. All this means gaining precious seconds. Having instantly assessed the situation, it will be possible to launch an attack, leaving the nearest opponent behind.

There is one more little “secret” to getting away from the enemy quickly. We are talking about the instant start of a dash to the opponents' shield. The player who has mastered the ball needs to fix the landing after the jump or make at least the slightest pause. As soon as the toes (and not the entire foot!) touch the ground, the player, as if continuing the fall, tilts the body forward, vigorously pushes off and begins to dribble.

As soon as the toes (and not the entire foot!) touch the ground, the player, as if continuing the fall, tilts the body forward, vigorously pushes off and begins to dribble.

* * *

And now let's look at several combinations for organizing a quick breakthrough with numerical superiority.

Scheme 1. Having caught the ball bouncing off the backboard in a jump, player 4 immediately, in the air, turns his back to his nearest opponent m, landing, begins to dribble the ball approximately along the longitudinal axis of the site. Players 6 and 7, who are closer to the opponent's shield, pass along the sidelines and, together with partner 4, create a numerical superiority (three against two).

Assume that player 5 has the ball (Diagram 2). He immediately starts dribbling, moving forward and slightly away from the longitudinal axis of the site. Meanwhile, player 4 breaks away from opponent 4, while players 6 and 7 advance along the touchlines. This creates a numerical superiority (four against three).

Scheme 3. Player 3 took possession of the ball. His task is to immediately bypass his closest opponent with the help of a dribble. If this is not possible, he continues to dribble to the sideline in order to create a comfortable position to pass the ball to teammate 6. This player, seeing that his partner has started to dribble to the sideline, must in turn create a safe position to receive the ball.

At this time, player 4, turning over his left shoulder, makes a dash, leaving behind the nearest opponent, and

receives the ball from player 6. After the pass, player 6, like player 7, runs along the touchline to the opponent's basket.

Screens can also be used to organize a fast break with superior numbers after catching the ball. They can be placed for each other by players who fought for a ball that bounced off their shield, or by one of the fast players, whose opponent obviously does not pose a great danger. It is advisable to use the barrier after a successful throw (when throwing the ball in from behind the end line).

Diagram 4 shows how this is done, for example. When throwing into the basket, one of the fast players (7) approaches the opponent's center forward 4 (the slowest player).

Suppose the ball hit the basket. Then player 7 puts up a barrier to the opponent's center, preventing him from returning to the defense in time and watching his ward. As soon as the screen is set, player 4 quickly breaks away from the opponent and moves forward. Player 3 throws the ball from behind the endline to teammate 6, who passes to the outgoing player 4. Then players 6 and 7 pass along the sidelines. Even if the attacking team fails to create a numerical superiority, it will have the advantage of a few seconds gained. Now the tall attackers of this team can complete the attack without interference from the center (4) opponent, who will inevitably be late with defensive actions.

The same combination will be quite effective after successfully catching the ball that bounced off his backboard.

You can create a wonderful position for organizing a fast break and with the help of the transmission (diagram 5). Suppose one of the three attackers of the opponent could not participate in the fight for the bounced ball, since one of the defenders (for example, player 5) managed to block his path, stopping him far from the backboard.

If player 4 gets hold of the bounced ball, he immediately passes to player 5, who has his back to opponent 5. Having caught the ball, player 5 advances to the opponent's shield with the help of a dribble. If player 3 takes possession of the rebounded ball, he passes it to partner 6 (perhaps after dribbling along the touchline). Player 5 at this time rushes to the middle of the court, where he receives the ball from partner 6.

When the players move towards the opponent's backboard, the ball is passed as soon as possible -

- to the attacker who passes the court along its longitudinal axis. The player who received the ball is responsible for dribbling. In order not to reduce the speed of movement, the dribble should be high.

In order not to reduce the speed of movement, the dribble should be high.

I would like to give a warning: be careful, do not rush to pass the ball until the final stage of the attack. Extra passes can lead to a loss of the ball (interception, inaccuracy) or to a violation of the zone rule. However, if, on a fast break, the attacker with the ball meets opposition from the defender who tries to stop him or intercept the ball, he must immediately pass to one of the free partners.

In the final phase of the attack, the player with the ball continues to dribble until one of the defenders begins to challenge him. As soon as this happens, you should immediately pass the ball to the partner who has freed himself from the defender. If the defenders, while retreating, cover the wingers, the player in possession of the ball continues to dribble and completes the attack. But at the same time, the wingers should not hide behind the backs of the defenders, but by active actions create a comfortable position for themselves to receive the ball. Several combinations of the fast break end phase are shown in Diagrams 2, 3, and 5.

Several combinations of the fast break end phase are shown in Diagrams 2, 3, and 5.

* * *

A quick breakthrough with the numerical equality of attackers and defenders is also a sharp offensive weapon. This can be demonstrated by examples of several combinations.

Of course, in the case when the player of the attacking team is face to face with the defender, the successful capture of the basket depends entirely on the level of the attacker's individual technical skill. For example, he can mislead the defender by quickly changing the direction of the dribble, or, without stopping the dribble, make a feint - a distracting movement of the body to induce the opponent to rush in one direction, while he himself passes in the other.

In a two-on-two fight (Scheme 6), player 6 starts the dribble, showing that he wants to break through to the backboard. At this moment, player 7 changes direction, receives the ball from partner 6 and breaks through to the basket.

Player 6 makes it easier for him to break through - by giving the ball, he immediately puts up a barrier to opponent 7. If defender 6 rushes to attacker 7, then he will leave player 6 free.

If defender 6 rushes to attacker 7, then he will leave player 6 free.

Variants are also possible here - attacker 7 (without the ball) on the move puts a barrier to defender 6 or attacker 6 suddenly and abruptly changes the direction of movement and breaks through to the basket.

In a three-on-three attack (diagram 7), player 6 goes to screen defender 5. At the same time, attacker 7 dribbles towards player 6. Player 5 abruptly changes direction. Freed from marking with a double screen, he receives the ball from partner 7 and shoots for the basket. If the defender guarding player 7 switches to attacking attacker 5, he immediately returns the ball to teammate 7.

The same combination can be used if player 6 has the ball.

You can also use the “three” on the move very effectively (passing in one direction, screening in the other).

In all cases, you must strive to attack quickly! Even if a quick breakthrough fails, the attackers will still achieve a certain advantage.