Home »

Misc »

How do deaf people play basketball

How do deaf people play basketball

Basketball is a game of sign language

“March is the most exciting time of the year,” says my sports fanatic brother. It is true though, March is one of the most thrilling times in the United States for college basketball.

Specifically, March is the month of the big tournament where the four best college basketball teams compete. Now is the time college basketball fans in the US fill out their brackets and place bets on who they think is going to win the overall tournament. According to David Pardum of ESPN.com, the American Gaming Association estimates that 70 million brackets would be filled out for this month’s tournaments.

With all this basketball talk around me, I started thinking more about my experiences with basketball, as someone with hearing loss.

With my hearing aids I can hear a lot of sounds, such as the referee whistle and the buzzing of the buzzer, but I had more difficulty hearing others talk on the court. I then became more curious about how other deaf and hard of hearing athletes communicate in the midst of playing a team sport such as basketball.![]()

How do those deaf basketball players communicate on the court?

Nonverbal Communication

I stumbled upon an article about the Gallaudet University basketball team. Gallaudet is the only deaf university with a basketball team in the world, making them truly one-of-a-kind. The article mentions how the basketball team has strong defense, and that basketball defense is all about communication.

The players are constantly looking at their coaches and looking at each other. Nonverbal communication is strong out on the court. The players will keep eye contact with one another, rely on facial expressions, body language and hand signals.

“The players will keep eye contact with one another, rely on facial expressions, body language and hand signals.”

Other well-known hard of hearing basketball players such as Lance Allred and Tamika Catchings have mentioned ways in which they use nonverbal behaviors to succeed in basketball.

Lance was the first legally deaf NBA player and played for the Cleveland Cavaliers.

“The beauty of basketball is that it’s a universal language,”he told the Utah Desert News.

Visual Cues

His advice to other deaf and hard of hearing basketball athletes is that they should play visually. They should read the body language of other players and use their strengths when out on the court.

Tamika Catchings is a retired basketball player who played for the WNBA team the Indiana Fever and also on the US Olympic team. She is a three-time Olympic gold medal winner and a WNBA championship holder. Having a hearing loss since she was a child gave her a strong work ethic and helped shape her into the basketball player she is today, she told the Hearing Health Foundation.

Like Lance, she too is extra observant on the basketball court, constantly looking at her coach and teammates.

“I read lips [and am] very observant, so I’m always looking around to see if there’s anybody talking to me, or I look at the bench to see if the coach is calling a play. Basketball is a game of sign language,” she says, according to Hearing Health Foundation.

Basketball is a game of sign language,” she says, according to Hearing Health Foundation.

“Basketball is a game of sign language.”

Not only is body language important in basketball, but it is also important in other sports.

Having a hearing loss often makes a person more aware of body language. Nonverbal cues are used in American football, baseball and between athletes and coaches. By being hard of hearing, you are automatically attuned to body language and nonverbal cues to help you hear.

After learning more about how athletes learn and adapt to body language on the court and field, it made me realize that these amazing attributes aren’t always highlighted, but are so important.

When thinking about sports, have you noticed that you are more observant than your teammates in sports? How has it helped you be successful when playing sports? Leave a comment with your sports story!

Author Details

Kirsten Brackett

Kirsten is the managing editor of Hearing Like Me. She has a moderate hearing loss and currently wears Phonak Audéo B-R rechargeable hearing aids. Outside of working for Hearing Like Me, she can be found exploring new cities, trying out new recipes in her kitchen, or hiking. She loves learning about different cultures and languages.

She has a moderate hearing loss and currently wears Phonak Audéo B-R rechargeable hearing aids. Outside of working for Hearing Like Me, she can be found exploring new cities, trying out new recipes in her kitchen, or hiking. She loves learning about different cultures and languages.

Basketball and the Deaf

Basketball And The Deaf

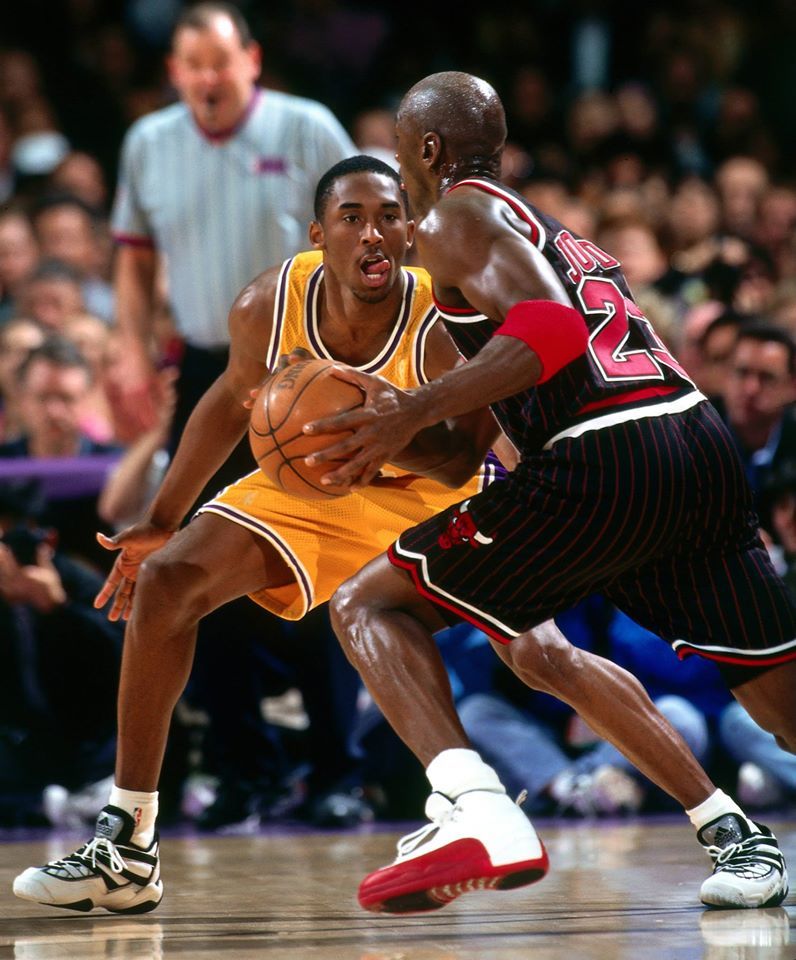

Hunter Clark

Basketball is loved all over the world by millions of people from all different backgrounds. All basketball players face some type of challenge; not tall enough, not strong enough, not fast enough, not skilled enough. Players in the Deaf community face these exact same challenges. In addition they also face the challenge of living in a hearing world, which is something they have had to overcome their whole life. In basketball, the Deaf or Hard of Hearing need to be able to communicate on the court during a fast-paced, chaotic game without being able to hear. Even though some game communication is not verbal, a lot is verbal especially in the traditional hearing setting. So how do Deaf teammates, coaches and officials communicate during the frenzy of a running game? Many including the Deaf community love this quick action-packed game of basketball. The love of the game is as long as the game has been around but the history of Deaf Basketball is short in regard to specific Deaf Leagues. Collegiate athletic scholarships have had a short history as well. For anyone to earn an athletic scholarship in today's competitive world of sports is a rare accomplishment. So what are the odds for Deaf basketball players to earn an athletic scholarship in comparison to a hearing person? Deaf basketball is just the same as hearing basketball the difference lies in the communication. (Page, 2014).

Even though some game communication is not verbal, a lot is verbal especially in the traditional hearing setting. So how do Deaf teammates, coaches and officials communicate during the frenzy of a running game? Many including the Deaf community love this quick action-packed game of basketball. The love of the game is as long as the game has been around but the history of Deaf Basketball is short in regard to specific Deaf Leagues. Collegiate athletic scholarships have had a short history as well. For anyone to earn an athletic scholarship in today's competitive world of sports is a rare accomplishment. So what are the odds for Deaf basketball players to earn an athletic scholarship in comparison to a hearing person? Deaf basketball is just the same as hearing basketball the difference lies in the communication. (Page, 2014).

Teamwork is what makes a basketball team great. In order to have teamwork you must have good communication. So how do Deaf players, coaches, and referees communicate? For Deaf players it is similar to how hearing players communicate. Each team has their own defense and sets on offense and different words or signs that represent their defense and offensive sets to inform them which ones to run. (Wilken, 2012). Deaf players must rely mostly on body language and signing in order to keep the game going. (USA Deaf Sports Federation, 1996-2015). The player with the ball (typically the point guard) must be a leader and make sure everyone knows what plays, offense or defense to execute. For all basketball players and teammates the more they play together the more they learn, become familiar with and expect certain styles, habits or type of "game" (the way the player plays, fancy, old-school, out of control, etc.). Teammates who work together and communicate well pick up on their teammates style fairly quickly. For the Deaf basketball player, their senses in picking up on these body language habits are usually keen. It is essential to know their teammates' styles so they know what to expect when the quickness of verbal communication is not an option.

Each team has their own defense and sets on offense and different words or signs that represent their defense and offensive sets to inform them which ones to run. (Wilken, 2012). Deaf players must rely mostly on body language and signing in order to keep the game going. (USA Deaf Sports Federation, 1996-2015). The player with the ball (typically the point guard) must be a leader and make sure everyone knows what plays, offense or defense to execute. For all basketball players and teammates the more they play together the more they learn, become familiar with and expect certain styles, habits or type of "game" (the way the player plays, fancy, old-school, out of control, etc.). Teammates who work together and communicate well pick up on their teammates style fairly quickly. For the Deaf basketball player, their senses in picking up on these body language habits are usually keen. It is essential to know their teammates' styles so they know what to expect when the quickness of verbal communication is not an option. (USA Deaf Sports Federation, 1996-2015). Understanding your teammate's strengths and weaknesses is vital for both the hearing and the Deaf basketball player. As long as they play together as a team and pay attention and apply what the coach instructs the Deaf basketball team can compete with just as much intensity if not, better than a hearing team.

(USA Deaf Sports Federation, 1996-2015). Understanding your teammate's strengths and weaknesses is vital for both the hearing and the Deaf basketball player. As long as they play together as a team and pay attention and apply what the coach instructs the Deaf basketball team can compete with just as much intensity if not, better than a hearing team.

To increase a team's intensity and competitiveness, the coach has to have trust and confidence in his players. Coaches for Deaf basketball players typically communicate through sign language and one-word signs representing certain plays, offense sets or defense. (United States of America Deaf Basketball, 2015). Many times the coach will also have a translator to help break the language barrier for basketball coaches who are not fluent in sign language. (United States of America Deaf Basketball, 2015). If a coach feels that having a translator will take away from his teaching and/or coaching ability then it is common for the coach to take courses in sign language. (Deaf Basketball Australia, n.d.) An inspiring story is that of Coach Kevin Cook. Coach Cook suffers from Parkinson's disease and coaches a girls Deaf basketball team. (CBS News, 2011). Coach Cook says these girls are mentally tough. (CBS News, 2011). His team fights through diversity and always tries to find a way to win. (CBS News, 2011). Having Parkinson's disease often causes Coach Cook to uncontrollably shake which sometimes makes signing plays to his team impossible. (CBS News, 2011). He shared that his shaking can cost his team 6-10 points a game. (CBS News, 2011). With the help of his assistant coaches who have a high basketball IQ, he can still get his players to understand what defense their in or what offense their running. (CBS News, 2011). In 2011, Coach Cook's team went undefeated with a record of 16-0 and won a State Title Championship. (CBS News, 2011). Coach Cook is a great example of how a Deaf basketball team can overcome all odds and how even a Coach who cannot always sign to his deaf team can find ways to communicate.

(Deaf Basketball Australia, n.d.) An inspiring story is that of Coach Kevin Cook. Coach Cook suffers from Parkinson's disease and coaches a girls Deaf basketball team. (CBS News, 2011). Coach Cook says these girls are mentally tough. (CBS News, 2011). His team fights through diversity and always tries to find a way to win. (CBS News, 2011). Having Parkinson's disease often causes Coach Cook to uncontrollably shake which sometimes makes signing plays to his team impossible. (CBS News, 2011). He shared that his shaking can cost his team 6-10 points a game. (CBS News, 2011). With the help of his assistant coaches who have a high basketball IQ, he can still get his players to understand what defense their in or what offense their running. (CBS News, 2011). In 2011, Coach Cook's team went undefeated with a record of 16-0 and won a State Title Championship. (CBS News, 2011). Coach Cook is a great example of how a Deaf basketball team can overcome all odds and how even a Coach who cannot always sign to his deaf team can find ways to communicate.

Officiating a game with Deaf players requires specific communication skills as well. For most officials the motto is they "see it and call it" and blow the whistle. (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). However, most players who are hard of hearing or Deaf will obviously not be able to hear the whistle blowing and will continue playing the game. Many fouls and travels are important to the flow and outcome of a game so when these types of infractions occur the official at a Deaf basketball must get the attention of the players by using body language and symbols to represent that a foul or infraction occurred during a play. (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). An interesting fact is that in the world of hearing basketball there are also Deaf officials. Chris Miller is a Deaf Division One Basketball Official in the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association). (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). Miller calls highly competitive games without the ability to hear. (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). He has successfully proven that a Deaf official can call a game just as good as a hearing official. (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). You might even speculate that a Deaf official calls a better game than a hearing official as they will never be distracted by the heckles and hollers of a relentless rowdy crowd who does not like a call or an angry coach or hostile player who wants to argue. However, most officials who are Deaf work in the Deaf Basketball Leagues.

He has successfully proven that a Deaf official can call a game just as good as a hearing official. (Deaf Basketball Officials, 2015). You might even speculate that a Deaf official calls a better game than a hearing official as they will never be distracted by the heckles and hollers of a relentless rowdy crowd who does not like a call or an angry coach or hostile player who wants to argue. However, most officials who are Deaf work in the Deaf Basketball Leagues.

Basketball for the Deaf has basketball leagues just like basketball for the hearing has different leagues. To play in a Deaf Basketball League the player must have a minimum 55% hearing loss. (Wilken, 2012). Players are not allowed to wear hearing aids, if any enhanced hearing technology or aids are found on a player while they are playing, they will be ejected. (Wilken, 2012). Art Kruger is the man behind the mind that organized Deaf Sports. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). The Deaf League was established in 1948 and slowly grew. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). By the year 2000, it had became more organized and better known. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). Kruger is known as "The Father of AAAD." (Panara and Panara, n.d.). AAAD is the acronym that stands for the American Athletics Association of the Deaf. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). One of the branches of the AAAD is the USADB (United States of America Deaf Basketball). (Panara and Panara, n.d.). The USADB is similar to the NBA (National Basketball Association) for hearing players. There is also the Worldwide Deaflympics. (International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, 2015). The USA participates in the Deaflympics with a Deaf elite basketball team comprised of Deaf basketball players that compete against other countries and their Deaf athletes. (Panara and Panara, n.d.) The Deaflympics started in 1924 in Paris and grew fast. (International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, 2015). In 2009, the Men's USA team won their 14th consecutive gold medal. (Whited, 2009).

(Panara and Panara, n.d.). By the year 2000, it had became more organized and better known. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). Kruger is known as "The Father of AAAD." (Panara and Panara, n.d.). AAAD is the acronym that stands for the American Athletics Association of the Deaf. (Panara and Panara, n.d.). One of the branches of the AAAD is the USADB (United States of America Deaf Basketball). (Panara and Panara, n.d.). The USADB is similar to the NBA (National Basketball Association) for hearing players. There is also the Worldwide Deaflympics. (International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, 2015). The USA participates in the Deaflympics with a Deaf elite basketball team comprised of Deaf basketball players that compete against other countries and their Deaf athletes. (Panara and Panara, n.d.) The Deaflympics started in 1924 in Paris and grew fast. (International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, 2015). In 2009, the Men's USA team won their 14th consecutive gold medal. (Whited, 2009). The USA team has been almost unstoppable winning the bronze in 2011 and a silver in 2012, 13 and 14. (Whited, 2009).

The USA team has been almost unstoppable winning the bronze in 2011 and a silver in 2012, 13 and 14. (Whited, 2009).

Tamika Catchings is a female basketball player who has won three consecutive gold medals as a Deaf athlete in the "hearing" Olympics proving many Deaf athletes compete in hearing athletics as well. (Audicus, 2014). Overcoming the challenges of playing in a Deaf League is a great accomplishment in itself. However, a Deaf player who competes in a hearing league faces additional challenges. (Wilken, 2012). Although it may seem these challenges could be overwhelming, deaf athletes do it every day. Catchings received the WNBA (Women's National Basketball Association) MVP (Most Valuable Player) award in 2011 for her hard work playing on the women's basketball team. (Audicus, 2014). Lance Allred is the only deaf basketball player to play in NBA history. (Fischer, 2014). In the years of 2005-2007, he played for the Cleveland Cavaliers. (Fischer, 2014). Allred started eight games and in his career averaged 2. 3 points and 2.2 rebounds. (Basketball-Reference.Com, n.d.). Before going to play in the pro leagues overseas, Lance Allred played several years in the NBA Development League or the "D-league" which is for players just on the border of making it into the NBA. (Wilken, 2012). Lance Allred is just the first in hopefully a long line of Deaf players to come.

3 points and 2.2 rebounds. (Basketball-Reference.Com, n.d.). Before going to play in the pro leagues overseas, Lance Allred played several years in the NBA Development League or the "D-league" which is for players just on the border of making it into the NBA. (Wilken, 2012). Lance Allred is just the first in hopefully a long line of Deaf players to come.

Despite not being able to hear, deaf players have some advantages. Deaf players most likely rely on eye site and are often visual learners. When a coach is showing a play or showing a drill the deaf player will probably pick it up quicker than the hearing player. If a player makes a mistake and the deaf player sees it then he will know not to do it. Deaf players have to work just as hard if not, harder they hearing players. Some Deaf players might not think of hard work as painful because they have had to work through difficulties their whole life. (Wilken, 2012).

So is it harder for a Deaf athlete to earn a collegiate basketball scholarship? There does not appear to be any statistical research on the number of Deaf athletes who receive college scholarships based on their athleticism. Logically, it could be assumed that a Deaf athlete has more of a challenge obtaining athletic scholarships due to a bias of schools and coaches assuming a hearing athlete would be a better player than a Deaf athlete. It would seem the chances of a Deaf player receiving an athletic scholarship would be next to impossible but, it has been done. Michael Lizaragga who played at Cal State Northridge College not only made it to college but also had a successful career. (Markazi, 2010). Michael Lizaragga received an athletic basketball scholarship his senior year in high school. (Markazi, 2010). In his junior year in college, he averaged almost 20 points per game. (Fox Sports, n.d.).

Logically, it could be assumed that a Deaf athlete has more of a challenge obtaining athletic scholarships due to a bias of schools and coaches assuming a hearing athlete would be a better player than a Deaf athlete. It would seem the chances of a Deaf player receiving an athletic scholarship would be next to impossible but, it has been done. Michael Lizaragga who played at Cal State Northridge College not only made it to college but also had a successful career. (Markazi, 2010). Michael Lizaragga received an athletic basketball scholarship his senior year in high school. (Markazi, 2010). In his junior year in college, he averaged almost 20 points per game. (Fox Sports, n.d.).

It is rare for anyone to make it to the NBA. There are about 26 million basketball players in the USA. (Sports & Fitness Industry Association, 2012). There are 1,984 colleges that offer a basketball scholarship. (Scholarship Stats.Com, 2013-2014). There are 30 teams with 16 D-league teams and there are only about 450 spots in the NBA. (Wehr, 2014). In its entire history there have been only 3,071 players who have played in the NBA. (Wehr, 2014). That is a small number of Pro players for the 70 years of the NBA. So the chances of a Deaf player to make it to the NBA is close to none. Due to their perseverance, many players have played in highly competitive overseas leagues. Lance Allred is the only male Deaf player who has made it to the NBA. (Basketball-Reference.Com (n.d.).

(Wehr, 2014). In its entire history there have been only 3,071 players who have played in the NBA. (Wehr, 2014). That is a small number of Pro players for the 70 years of the NBA. So the chances of a Deaf player to make it to the NBA is close to none. Due to their perseverance, many players have played in highly competitive overseas leagues. Lance Allred is the only male Deaf player who has made it to the NBA. (Basketball-Reference.Com (n.d.).

When push comes to shove it is all just a matter of how hard you work. The Deaf might have to work harder to understand and overcome communication boundaries. The love of basketball has always being in the Deaf community. Now with the Deaflympics and USADB Deaf Basketball is more organized and becoming more known. The game is loved all over the world. Basketball is a universal language. For some, the ball is all they need to feel free. For some, the ball is what relaxes them. To some, the ball lets them show people they are just like everyone else. To some, the ball lets them show people they are not like everyone else and the ball sets them apart. To some, the ball opens a new world, fills a gap, or takes them out of a place they don't want to be in. To some, the ball is life. The ball doesn't care whether it is heard or not and this is especially true in Deaf Basketball.

To some, the ball lets them show people they are not like everyone else and the ball sets them apart. To some, the ball opens a new world, fills a gap, or takes them out of a place they don't want to be in. To some, the ball is life. The ball doesn't care whether it is heard or not and this is especially true in Deaf Basketball.

REFERENCES

Audicus (2014, October 8). 9 Olympic Athletes Who Beat Hearing Loss. Retrieved from https://audicus.com/9-olympic-athletes-who-beat-hearing-loss/

Basketball-Reference.Com (n.d.) Lance Allred. Retrieved from http://www.basketball-reference.com/players/a/allrela01.html

CBS News. (2011, January 28). Deaf Basketball Teams Amazing Comeback. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot7mWASecos

Deaf Basketball Australia (n.d.) Coaching Deaf Basketballers. Retrieved from http://www.foxsportspulse. com/assoc_page.cgi?c=1-5096-0-0-0&sID=228501

com/assoc_page.cgi?c=1-5096-0-0-0&sID=228501

Deaf Basketball Officials: See It Call It. (2015, March 22). Retrieved from http://www.deafbasketballofficials.com/history.html

Fischer, C. (2014). Lance Allred: The First Legally Deaf Player in the NBA. Retrieved from http://www.deafandhoh.com/lance_allred.html

Fox Sports (n.d.). College Basketball. Retrieved from http://www.foxsports.com/college-basketball/michael-lizarraga-player

International Committee of Sports for the Deaf. (2015) History. Retrieved from http://www.deaflympics.com/icsd.asp?history

Markazi, A. (2010, March 13) Deaf Players Teammates See Inspiration. Retrieved from http://sports.espn.go.com/los-angeles/ncb/columns/story?id=4970355

Page, C. (2014, January 8). Deaf Basketball vs. Hearing Basketball. Retrieved from https://prezi.com/xkgajeb4ctjj/deaf-basketball-vs-hearing-basketball/

Panara, R. and Panara, J. (n.d.) Great Deaf Americans. Retrieved from http://usadb.us/court/images/history/history-artkruger.pdf

and Panara, J. (n.d.) Great Deaf Americans. Retrieved from http://usadb.us/court/images/history/history-artkruger.pdf

Scholarship Stats.Com (2013-2014). Chances of a High School Athlete getting an Athletic Scholarship. Retrieved from http://www.scholarshipstats.com/scholarshipodds.html

Sports & Fitness Industry Association. (2012. March 12). Over 26 Million Americans Play Basketball. Retrieved from https://www.sfia.org/press/433_Over-26-Million-Americans- Play-Basketball

SVRS. (2015, April). USADB Annual Tournament. Retrieved from http://www.sorensonvrs.com/april_2015_usadb_annual_tournament

United States of America Deaf Basketball. (2015, April 22). Retrieved from http://usadeafbasketball.org/

USA Deaf Sports Federation. (1996-2015). History. Retrieved from http://www.usdeafsports.org/about/history/

Wehr, J. (2014, January 22). There have been 3,071 NBA players over the past 50 years. Guess how many had a better start than James Harden. Retrieved from http://www.red94.net/3071-nba-players-past-50-years-guess-many-better-start-james- harden/13856/

Guess how many had a better start than James Harden. Retrieved from http://www.red94.net/3071-nba-players-past-50-years-guess-many-better-start-james- harden/13856/

Whited, C. (2009, September 14). Golden A 14th time!: Men's Basketball Avenges Loss to Lithuania with 90-73 win. Retrieved from http://2009.usdeaflympics.com/articles/article/2009/sep/14/golden-14th-time/

Wilken, K. (2012, May 15). Basketball and The Deaf. Retrieved from http://www.lifeprint.com/as1101/topics/basketball-and-the-deaf.htm

Also see: "Basketball and the Deaf" By Katie Wilken

Notes: The "Basketball and the Deaf" article by Hunter Clark was submitted 8/23/2015.

* Want to help support ASL University? It's easy: DONATE (Thanks!)

* Another way to help is to buy something from Dr. Bill's "Bookstore."

Bill's "Bookstore."

* Want even more ASL resources? Visit the "ASL Training Center!" (Subscription Extension of ASLU)

* Also check out Dr. Bill's channel: www.youtube.com/billvicars

You can learn American Sign Language (ASL) online at American Sign Language University

ASL resources by Lifeprint.com Dr. William Vicars

The Only Deaf Player in Professional Tennis - With the World Across the Line - Blogs

Ben Rothenberg's story from The New York Times about Korean youth Dok-Hee Lee who strikes at the fundamentals of tennis.

“In order to improve their chances of success in the youth team tournament at the Asan National Sports Festival, the Mapo Seoul High School team invited a player from Jecheon, located two hours from the capital city. His name is Dok-Hee Lee, and he first attracted the attention of coaches in elementary school.

The Mapo players pressed against the dusty court and cheered for Lee as he hammered forehands in the final match. He quickly won with a score of 6:1, 6:1, and this is not surprising - he is the best player under 20 years old in South Korea, a professional, 143rd racket in the world.

"His level of skill, power and reception is much higher than usual at the high school level," said Yong Jong Suk, with whom he played in pairs at the tournament.

But even among the elite players, 18-year-old Lee stands out. He is deaf, and in the history of the sport, deaf players have never reached such heights before.

In tennis, it's not enough just to see the ball. Top players claim they react faster when they hear the ball, a key advantage in a sport where lightning fast serves and powerful bounce shots make every split second count.

“There are a lot of different spins in tennis, and I can tell by the sound which one a player has put in because I know what they sound like,” says Katie Manzebo, a college tennis coach and volunteer coach for the USA Deaf Team. “But deaf players don’t know that sound, so they have to focus on what the opponent is doing, how the racket hits the ball, how the ball looks when it goes over the net.”

“But deaf players don’t know that sound, so they have to focus on what the opponent is doing, how the racket hits the ball, how the ball looks when it goes over the net.”

Chu Hyun Chan, a coach at Mapo High School, says he was initially skeptical about Lee's potential.

“When we first met, I thought that deafness would prevent him from becoming a strong player. But his progress gave me confidence. Now I am confident that he will succeed.”

Lee is the second racket of the world among professionals under 18 years old, and he immediately began to shine. So far, he has no matches in the main draws of ATP tournaments or Grand Slams, but in September in Taiwan he already played in the Challenger final, and then reached the semi-finals twice more.

And if Lee continues to progress, he will destroy a number of established ideas about the intricacies of tennis.

Studies have shown that a person responds faster to an auditory stimulus than to a visual one. According to data compiled last year by the National Institutes of Health, the reaction time to a visual stimulus is 180-200 milliseconds, and to a sound stimulus - 140-160.

According to data compiled last year by the National Institutes of Health, the reaction time to a visual stimulus is 180-200 milliseconds, and to a sound stimulus - 140-160.

At Wimbledon 2003, Andy Roddick said that his hearing is the first to react to an opponent's blow - he also reads the first information about the shot taken.

“You can hear how hard the person hit the ball. If the blow is strong and flat, then a pop is heard. You probably understand the sound faster than you see the ball. For example, if the opponent shortened, I suddenly hear that the ball did not fly off the racket. This is part of the reaction process. I believe that to play at the highest level you need to clearly hear the ball.

Todd Perry, a former doubles player who is now a coach, says he often listens to his students hit to see where he can improve.

“The coach can hear a clean hit and only with the help of sound can he make changes so that the hit is clean. If you carefully listen to the strikes of different players, it becomes clear that the sound of each is different.

In his seminal 1974 work, The Inside of the Game of Tennis, Timothy Galwey urged focus on sound and described how paying close attention to the sound of one's own game allows one to recreate the "crunch" of a successful shot.

“I realized how effective a stimulus for our internal computer can be the memorization of certain sounds,” wrote Galwey. “When a person listens to their own forehand, they can remember the sound of a good hit. As a result, the body tends to repeat the behaviors that led to that sound.”

Martina Navratilova was one of the main proponents of careful attention to the sound of the game. She calls loud moans cheating because they mask the sound of the blow. At the 1993 US Open, she blamed overhead planes for interfering with the game.

“The sound of impact is very important, especially near the net,” said Navratilova. - First you hear the ball. Then, based on their sound, you react to speed and rotation. And when you don't hear it, the system collapses. I missed some volleys because I didn't hear the ball."

I missed some volleys because I didn't hear the ball."

Andy Murray also had a hard time in the cacophony of this year's US Open, as rain battered the new roof over Arthur Ashe Stadium.

“In the game we use our ears – not just our eyes. They help to evaluate the speed of the ball, rotation, force of impact. If we played with plugged ears or headphones, it would give an advantage to the opponent without headphones. Of course, it is possible to play, but it is certainly more difficult.”

Murray's hypothetical example was once put into practice. Tobias Burz, a deaf player who is now the technical director of tennis for the International Committee for Deaf Sports, played against an opponent who heard and ranked higher. After winning the first set 6-2, the opponent wondered what it was like to play as a deaf tennis player and put on earplugs and headphones. Burtz won the next set 6:3.

An unexpected diagnosis

Park Mi-cha and her husband Lee Sang-chin immediately realized that they had an unusual son, but they did not seek a diagnosis. Lee Dok-hee was born when his father was doing his mandatory service in the South Korean army, and Park was left alone with her son. She hoped that everything would go away on its own.

Lee Dok-hee was born when his father was doing his mandatory service in the South Korean army, and Park was left alone with her son. She hoped that everything would go away on its own.

When her son was two years old, Park took him to Seoul for an examination. "The doctor just said, 'This child can't hear anything, he's deaf.' I was very surprised, I didn't know how to react. But I knew I couldn’t just pick up and go home,” she recalls.

Park went to her sister's house in Seoul and was overcome with emotion. “When I saw her, grief and sadness came over me, and I could not stop crying.”

After a few hours she calmed down and called her husband. He came for her from Jecheon. On the way home, they decided not to lose heart.

“We didn't discuss how sad it all was, but how we could support and raise our son,” she says. “This is our firstborn. We were sad for about a week, and then we had the courage to move on to the next stage, to start looking for an opportunity for him to get an education.

When Dok-hee was four, his parents enrolled him in a school for the disabled in Zhongju, an hour's drive from home. Most of the students lived there in the boarding school and saw their parents only on weekends, Park was determined to spend more time with her son. She spent two hours every day on the road, and then began to send him to a regular school so that he would adapt to the world of hearing.

“I wanted it to be integrated. I saw high school students at a school for the deaf - they only knew sign language, so, for example, on the bus they had to write notes to the driver. And then they grew up, and the opportunities to find a job with a person who knows only sign language are very limited.”

Pak drew conclusions and began to teach her son how to speak and read lips by herself - she showed him cards depicting various mouth movements. A few years later, Dok-Hee left the school for the deaf. At the request of his parents, he did not learn sign language.

“Only a few percent of deaf students can integrate into society and earn their own living,” Park says. – Most give up, live with parents who fully provide for them. But we wanted Deok-hee to be independent and live like a normal person."

– Most give up, live with parents who fully provide for them. But we wanted Deok-hee to be independent and live like a normal person."

While in high school, Lee Sang-jin set a record in the 200 meters at the National Sports Festival. He decided that sport is the best way for his son. Considering that deafness would be an insurmountable obstacle to team sports, he focused on individual sports - golf, archery and bullet shooting. But Dok-hee made his own choice when he saw his cousin Woo Chun-hye playing tennis.

"I was very interested in watching tennis and I asked, 'Why can't I play?' My cousin gave me a racket, I tried hitting, I liked it. Tennis attracted me immediately - I liked swinging the racket, ”says Dok-Hee.

The parents also devoted themselves entirely to their son's nascent tennis career.

“It wasn't a hobby or entertainment – we were very serious,” Park recalls. - When his father and I first met with the coach, we said that this was not entertainment, that we were looking for a career for him in the future. So the attitude to classes should be serious. If he has no chance of success, then we will drop this business.

So the attitude to classes should be serious. If he has no chance of success, then we will drop this business.

Lee continued to live in his parents' apartment in Jecheon, where his mother worked as a hairdresser and his father worked as a journalist, but his tennis career began to attract national attention. He won in every age category, but many parents and coaches continued to doubt.

“Ninety percent of the coaches, parents, and relatives of other players said that Dok-hee couldn't turn pro,” says Park. “They said that at the school level the speed of the ball is very slow, so he manages. But with the pros, the ball flies very fast and he won't be able to react because he's deaf."

She adds: “We tried not to listen to such criticism. My husband and I wanted to secure a future for him. And we had nothing but tennis."

Collegiate success

Although no deaf player has achieved professional success comparable to Lee's, there have been several deaf or hard of hearing tennis players in the US who excelled at the collegiate level.

Paige Stringer, who founded the World Foundation for Children with Hearing Loss, played for the University of Washington and her partner in a couple was also deaf. She has a hypothesis that the lack of the ability to hear the blow of opponents can be compensated for by sight.

“Those who are born deaf or hard of hearing in general may have stronger intuitions and are generally better at reading faces and body language. When one sense organ is affected, the others work better to compensate for the loss. If my hypothesis is correct, people who are deaf and hard of hearing may have an advantage in tennis because they see clues more quickly that allow them to evaluate their opponent's plans. And they may have better reflexes because their eyesight is faster.”

Hard of hearing players often realize how important hearing is in tennis when they are forced to play without the hearing aids or cochlear implants they rely on in everyday life. Such things are forbidden in competitions for the deaf - for example, at the Deaflympics. The experience of playing with and without sound puts these people in a unique position to evaluate his role in tennis.

The experience of playing with and without sound puts these people in a unique position to evaluate his role in tennis.

Evan Pinter, who played for the University of Florida Gulf Coast, called the lack of sound of his own shots the main obstacle on the court.

“Without a hearing aid, I immediately feel uneasy,” says Pinter. - I prefer to play with the apparatus, because this way I can hear the ball much better. I always like to hear it rip off the strings when I hit the perfect shot - that sound gives me confidence."

Emily Hangstefer, who played for the University of Tennessee, also spoke about similar problems.

“While preparing for the Deaflympics, I realized that I rely on hearing rather than sight or feeling for the ball. It took me five weeks to start looking at the ball instead of listening. Having lost my hearing, I was forced to rely on other senses: touch and sight.

Careful reading of the game has become Lee's forte. Wu, his cousin and trainer, claims that he can predict an opponent's punch by looking carefully at his backswing. Christopher Rangkat, Lee's former rival, admires his ability to anticipate events.

Christopher Rangkat, Lee's former rival, admires his ability to anticipate events.

“He always seemed to know where I was going to hit,” Rangkat told reporters last year. “And I don’t think he guessed. He seemed to be reading my mind."

Striving to be the best

Lee wants to be the world No. 1, but first he wants to be the best player in South Korean history by beating Hyun Taika Lee, who was No. 36 in the world in 2007 and won one ATP singles title.

In Asia, tennis is less popular than baseball and football, and there are currently no ATP tournaments in South Korea. But the Korea Tennis Association is hoping that Dok-Hee Lee and another talented youngster, world No. 104 Hyun Chung, 20, will help the team return to the Davis Cup World Group, from which it was eliminated in 2008.

The association has a new leadership and hopes to use the raised funds to help Lee and Chung and to raise juniors. It is assumed that in winter the players will be sent to train in warmer countries.

Lee doesn't think being deaf will hurt him: "It doesn't matter," he says. But he admits that he has another physical problem - at 175 centimeters tall, he is a bush in the ship forest of professional men's tennis. Now in tennis, "physics" is playing an increasing role, and in the top 50 rankings there is only one player as tall as Lee: world No. 21 David Ferrer. Only six Top 50 players are under 182 centimeters.

Wu, who is his sparring partner and speaks some English, helps Li to take the first steps on the tour. Wu says Lee sometimes worries about being one of the youngest on the tour, but he has a very positive attitude and communicates calmly with colleagues.

On the court, Lee can fight almost without problems - except for the fact that sometimes he does not notice the requirement to replay the rally - but other requirements can cause him difficulties. All players are required to participate in press conferences after each match upon request of the media.

Non-verbal cues are easy for Lee to recognize, but interviews can be tedious because he has to lip-read the interpreter's speech. And his own speech is also quite difficult to understand. The Korean TV channel broadcast his interview after one of the matches at the sports festival with subtitles.

And his own speech is also quite difficult to understand. The Korean TV channel broadcast his interview after one of the matches at the sports festival with subtitles.

However, there may be advantages to Lee's unique situation.

“Of course, I want my player to be treated like everyone else, but his deafness gives us certain business advantages,” says the tennis player's agent. “Because no one has done anything like this before.”

An early supporter was Hyundai, which sponsored Lee when he was 13 and recently extended his contract until 2020. The company said in a press release that it is "amazed and inspired by the unwavering desire to reach the top of tennis despite being deaf." The company also stated that it, "as a responsible Korean company, has an obligation to support it."

Hyundai's funding has created Lee a stable financial base that a rare young player can boast of. His agent hopes that the new earnings - prize money and additional sponsorship - will someday allow him to travel permanently with a manager and an interpreter.